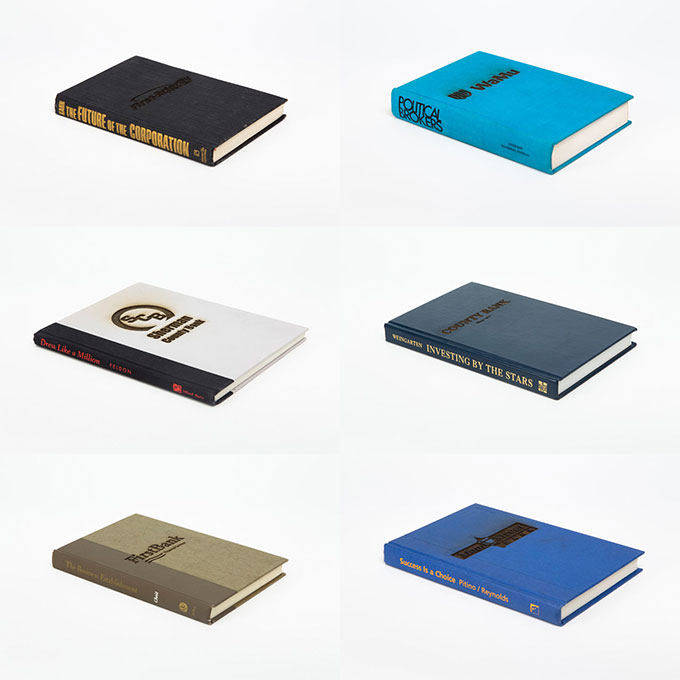

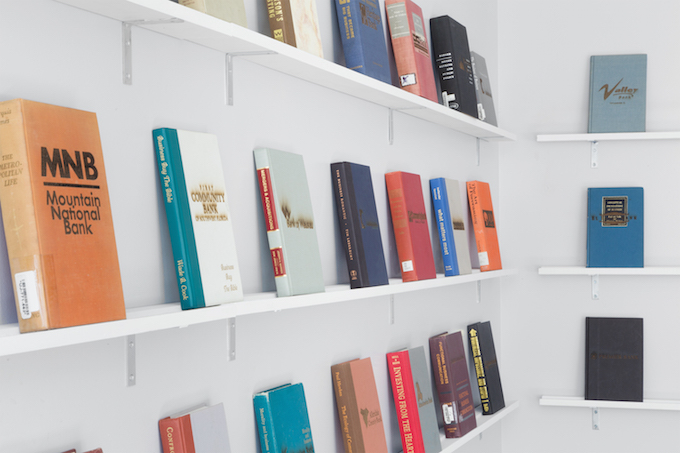

Installation View of Michael Mandiberg’s FDIC Insured at The Art-in-Buildings Financial District Project Space, New York, September 15-December 15, 2016. Courtesy Michael Mandiberg/Denny Gallery, NYC.

Creative Time Reports was conceived and launched as Occupy Wall Street took over Zuccotti Park. The movement informed many of the first pieces we commissioned, as well as much of our mission, in particular “speaking truth to power.” As an homage to the radical shifts in contemporary culture Occupy catapulted, I interviewed artist Michael Mandiberg on his project, FDIC Insured, a trove of investment guidebooks branded with the logos of more than 300 failed banks that were closed by the FDIC during the Great Recession. The books were purchased at the Strand Book Store in New York City. As Mandiberg describes, a mere weekend can seal the fate of a failed bank: “On Friday the bank is alive, but at 6 p.m. it begins a massive autopsy, and by Monday morning all traces of the original bank are gone. It is operated under the name of a formal rival bank, many of the employees are gone, and the entire visual signage has changed.” FDIC Insured plays with this curious late-capitalist temporality. It is a meditation, a memorial, an archive and a metaphor for the failures of a financial system.

Creative Time Reports: How did you arrive to the decision to sear logos of defunct banks into books for your FDIC Insured project, and how do you see the project as part of the cultural thrust of the Occupy Wall Street movement?

Michael Mandiberg: My decision to burn the logos into financial books arose from a confluence of factors: In the fall of 2008 I kept finding books left on people’s stoops—that they didn’t want, couldn’t sell, but didn’t just recycle, because they held some combination of sentimental and use value. I was at Eyebeam, so I experimented with the laser cutter to burn words into some of these books. At the same time I had been thinking a lot about the history and aesthetics of logos, as artist xtine burrough and I were completing Digital Foundations. And all around me, around us all, banks were failing.

This work is political, but I don’t see it primarily as an activist work. I see it functioning as a memorial, not to the banks themselves, but to the lives they have ruined. One of the visitors to the show found the book for the bank whose failure wiped out a family member’s retirement. The system tries to ignore its failure and just get on with things, but we haven’t gotten on with things—everyone but the 1 percent have come out worse off. The books are also suggestions of a world that could be otherwise, because they speak to the impermanence of the system. That it can fail, and it can end.

CTR: Why is it important that the books be exhibited where they are, so close to Wall St?

MM: The space helps set the tone. The books are installed in a recently vacated office suite, just off Wall Street. I thought it was symbolically important to exhibit them in the place where this problem started. We quickly forget, but during the Great Recession, there was a marked increase in “Space Available” signs displayed in office buildings.

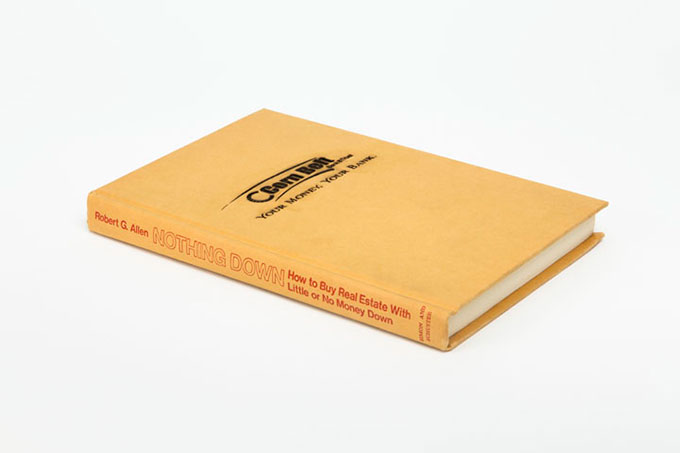

Michael Mandiberg, FDIC Insured, laser cut found book 2009-2010. Courtesy Michael Mandiberg/Denny Gallery, NYC.

CTR: What should we understand about these logos, beyond the names of the failed banks?

MM: Following the conventions of corporate design codified in the 1950s, these logos attempt to convey the banks’ authority, stability, and permanence through visual iconography. Greek columns, statehouses, mountains, leafy trees, and other symbols of historical and natural power appear frequently. Despite their aspirations to longevity, these logos—and the failure they represent—disappear from our memory, and are erased from the Internet without entering its many archives. This archive is a visual reminder of their failure, and the failure of their aesthetics of timelessness.

CTR: Did you do any deliberate matching, in terms of books and banks, or was it a random exercise?

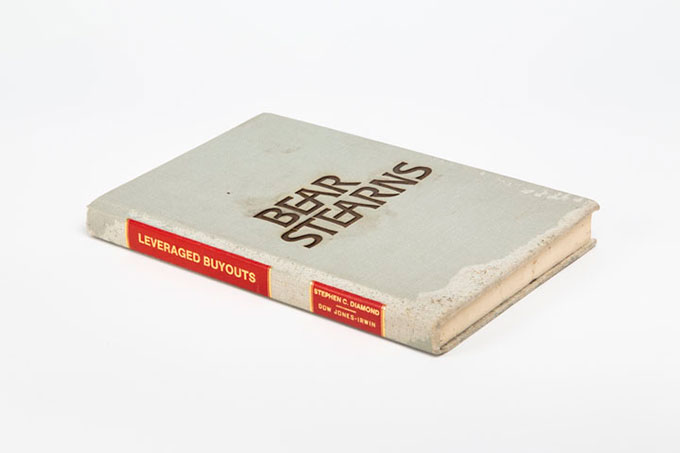

MM: I didn’t have to make specific decisions about matching logos and books: titles as florid as “Nothing Down: How to Buy Real Estate with Little or No Money Down,” or as mundane as “Leveraged Buyouts,” worked with whichever logo I paired them with. The first half of the books came from the $1 racks at The Strand bookstore in New York City. When I started working with library discards during the second half, if I had banks from the same state as the library, I would pair them.

Michael Mandiberg, FDIC Insured (Bear Sterns, New York NY, March 16, 2008), laser cut found book, 2009-2010. Courtesy Michael Mandiberg/Denny Gallery, NYC.

CTR: You’ve described the process of laser-cutting the books as “burning books,” how do you see that as relating to the intention of the work?

MM: The laser works by burning. It leaves a singed halo around the charred, bas-relief void. Even if a viewer doesn’t understand the role or mechanics of the laser, they smell the pungent odor and fully understand how the work was made: by fire. Like the crisis itself, the material evaporates into thin air.

CTR: FDIC Insured and Print Wikipedia seem to share a few common themes: the physical memorialization of things that are disappearing or constantly changing, and the serial nature and enormity of the works. How do you see the relationship between the works?

MM: I started both projects within a year of each other, and both took six to seven years to complete. With Print Wikipedia I transformed the entirety of the English-language Wikipedia database into 7,473 volumes of 700 pages each, complete with covers, and then uploaded them for print-on-demand. Both represent digital information by manifesting these archives in space. We think of these media as insubstantial and immaterial, per the metaphor of “the Cloud,” but the reality is that they are unstable, and quite material.

Authorship and ownership marks a key difference between the two. The Wikipedia corpus is a techno-utopian project produced collectively and shared in a digital commons through its Creative Commons license. FDIC Insured is an attempt to represent free market cycles of extraction and collapse.

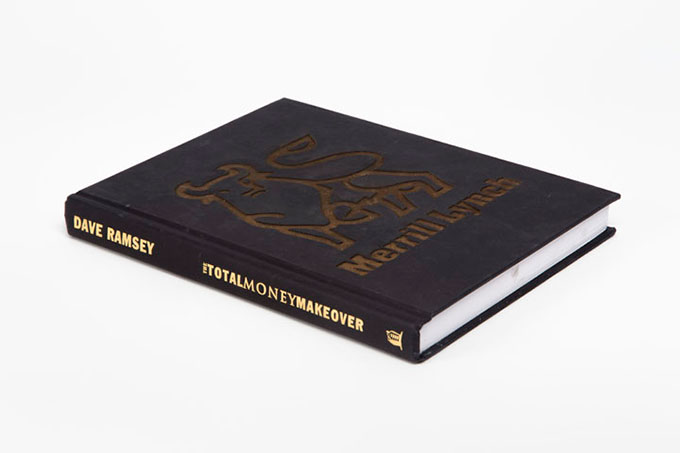

Michael Mandiberg, FDIC Insured (Merrill Lynch, New York NY, September 14, 2008), laser cut found book 2009-2010. Courtesy Michael Mandiberg/Denny Gallery, NYC.

CTR: Can you tell us about the Art+Feminism Wikipedia Edit-a-thons and how they address the gender gap that exists on the website? How does the project aim to create a new historical record?

MM: I am one of four co-founders of the Art+Feminism Wikipedia Edit-a-thons, a public project to improve coverage of women and the arts on Wikipedia, and to encourage female editorship, in response to the well-known gender gap. This aporia matters, as Wikipedia has become the largest repository of human knowledge and the content backbone of the Internet. Since 2014 we have organized annual edit-a-thons with hundreds of locations around the world, the participants of which edit or create thousands of articles. We are beginning to plan our March 2017 events, and welcome participants and organizers to get involved.

CTR: How, if at all, do the Edit-a-thons relate to your Print Wikipedia project?

MM: They are two sides of the same coin. Print Wikipedia is accompanied by a 36-volume Wikipedia Contributor Appendix which lists the names of the 7.5 million Wikipedia users who have made at least one edit. Print Wikipedia manifests the scale of this collectively authored work, and Art+Feminism attempts to change the collective and thus the text itself.

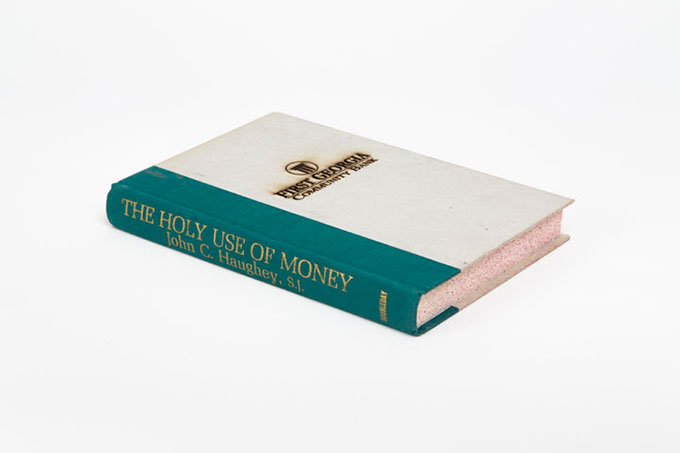

Michael Mandiberg, FDIC Insured (First Georgia Community Bank, Jackson GA, December 5, 2008), laser cut found book, 2009-2010. Courtesy Michael Mandiberg/Denny Gallery, NYC.

Michael Mandiberg, FDIC Insured (Corn Belt Bank and Trust, Pittsfield IL, February 13, 2009), laser cut found book, 2009-2010. Courtesy Michael Mandiberg/Denny Gallery, NYC.

Installation View of Michael Mandiberg’s FDIC Insured at The Art-in-Buildings Financial District Project Space, New York, September 15-December 15, 2016. Courtesy Michael Mandiberg/Denny Gallery, NYC.