Steve Mumford, Anbar, 2016. Oil on linen, 60 x 96 inches. Courtesy of the artist and Postmasters Gallery, New York.

A group of passengers are tightly clustered in a the open cockpit of a Blackhawk helicopter as it speeds low over the rural Iraqi terrain; a farmer looks up as the aircraft roars past, while the four passengers, lost in thought, contemplate their own disparate missions.

October 7th marked the 15th anniversary of the American invasion of Afghanistan, the longest war the US has been engaged in. While US troops in Afghanistan have been reduced to 8,400 – down by over 90% from the 2010 peak of 100,000 – little by little the Taliban are taking more territory, inflicting terrible losses on the Afghans.

Artist Steve Mumford reflects on his time in Afghanistan and on his work:

When the United States began their invasion of Iraq I became particularly interested in the work of Winslow Homer, a renowned 19th-century American painter and printmaker who had spent some time on the front lines of the Civil War. Winslow’s war paintings were humble scenes that spoke to the universal qualities of war—capturing, in vignettes, his impressions of the lives of soldiers off the battlefield. It was this universality of his work that inspired me to do something similar in Iraq, and later Afghanistan.

In the beginning I wasn’t able to get embedded with the U.S. military. So, I flew to Kuwait and got a ride with a couple of French reporters who were on their way to Baghdad, and was eventually able to embed with Army troops in Iraq. After a few trips, I became more comfortable drawing events in a war zone in real time, drawing whatever they did. Combat happens so quickly that it’s more of a photographer’s or photojournalist’s realm. Drawing doesn’t really lend itself to out-and-out combat; it’s better for capturing what happens in between the time the bullets are flying.

Steve Mumford, Female Barracks in Samarra, 2016. Oil on linen, 60 x 60 inches. Courtesy of the artist and Postmasters Gallery, New York.

Focused on a group of female soldiers at rest in their improvised plywood barracks, barely keeping out the heat of the midday sun. A young conscript cleans her weapon as her officer daydreams languidly in the foreground.

I didn’t have a lot of preconceptions about drawing from the front lines—I was not going in planning to take an anti-war stance. The idea was more to go and draw what was happening, to try to be true to the realities of the time and place as I experienced it.

A secondary part of the project has always been making large-scale oil paintings based on the war, back in my studio, and just recently I had a show of these works. War art has changed a lot over time. The quintessential artistic images of war are from artists in the vein of Jacques Louis David, glorifying a conqueror like Napoleon and his exploits, with grand landscapes and mass armies. But the template for my work was more along the lines of that made during World War II, when the armed services had their own artist corps—civilian artists who were working for publications like Life Magazine. That style of work was closer to Winslow Homer’s practice: a tradition of realism where people went armed with a pencil and paper, so to speak, and just drew what was happening.

Steve Mumford, Trisha and Brian at Camp X-Ray, Guantanamo, 2016. Oil on canvas, 120 x 192 inches. Courtesy of the artist and Postmasters Gallery, New York.

But the coda to the works in my most recent show is not from Iraq or Afghanistan at all, but from my trip in 2013 to Guantanamo Bay: Trisha and Brian at Camp X-Ray, Guantanamo, massive at 10 by 16 feet. I took two trips to Guantanamo Bay to draw for Harper’s Magazine, and the thing that was so striking about the visits was that I was never allowed to see any of the detainees while I was there; my experience there was much more censored than on any of my trips to Iraq or Afghanistan. I went to Guantanamo Bay after eight trips to America’s war zones. The detention facility overall was familiar—it had the feeling of other large military bases. But Camp X-Ray—the camp where they brought the first prisoners, and where detainees were waterboarded—was a different animal. It has been shuttered for ten years, and the whole place is now overgrown and jungle-like—the grasses are tall and vines cover the barbed wire. And there is nobody around. In the distance are bare hills that run along the border with Cuba.

The camp was hauntingly beautiful, and the soldiers who escorted me evinced the sort of quiet contemplation that one associates with a sacred space. Camp X-Ray is haunted by the ghosts of our post-9/11 venture into torture. It’s a vast and intensely lonely place. In depicting that intensity, I tried to capture the feeling of the American soldiers there who were in a sense caught; they had to follow their orders but their jobs took a toll on them. After all the pain, excitement and confusion of the last decade at war, Camp X-Ray seemed to encapsulate all the questions and ambiguities that brought us there, and left an abiding question of where to go from here. In my painting, Trisha, a female trooper, is looking forward—almost symbolically. We know where we’ve been, but what lies in our future?

As told to Olivia El-Sadr Davis.

Steve Mumford, The Prayer, 2016. Oil on linen, 48 x 60 inches. Courtesy of the artist and Postmasters Gallery, New York.

“The Prayer” pays tribute to the Renaissance tradition of portraying saints in the wilderness: a lone US soldier experiences a moment of spiritual contemplation or redemption in another indifferent landscape: a car, riddled with bullets sits by the berms and Hesco barriers meant to protect soldiers from an insurgent attack. A pair of helicopters track the horizon on some unknown mission; the sleepy life of the plains beyond the base, manifested in a shepherd with his flock, continues as it has for thousands of years.

Steve Mumford, Crossed Swords Monument, 2016. Oil on canvas, 36 x 72 inches. Courtesy of the artist and Postmasters Gallery, New York.

Steve Mumford, War Story, 2016. Oil on canvas, 20 x 20 inches. Courtesy of the artist and Postmasters Gallery, New York.

I was embedded with a platoon of Marines in Afghanistan, and they were going into an area that was actively hostile. The translator began to hear over the Taliban radio frequency that they were monitoring, that the Taliban saw us approaching. We knew that firing was about to start, and it turned into a running series of firefights for most of the day. There was a platoon to our east who spotted a man dressed like a farmer, but who looked like he was kind of surreptitiously talking into a cell phone. Given that there was all this shooting going on around him, they figured he was almost certainly a spotter for the Taliban. The Marine shot at him but missed him at a long distance, but he dropped down anyway. When we went to collect him, we found that the bullet had gone right through the shovel that he was holding up against his shoulder – he had just given up. After taking him in, he told the Marine interrogator that they could do whatever they wanted to with him, but he wasn’t going to tell them a damned thing. The Marine responded, “Well, we’ll just have to turn you over to the Afghans in that case,” and that was all I ever heard of it. The whole story was like the quagmire of Afghanistan in a nutshell, ironies, poignancies, and all.

Steve Mumford, Lost, 2016. Oil on canvas, 18 x 36 inches. Courtesy of the artist and Postmasters Gallery, New York.

Steve Mumford, Large IED, 2009. Oil on linen, 18 x 36 inches. Courtesy of the artist and Postmasters Gallery, New York.

Steve Mumford, Afghan Soldier, 2016. Oil on canvas, 24 x 24 inches. Courtesy of the artist and Postmasters Gallery, New York.

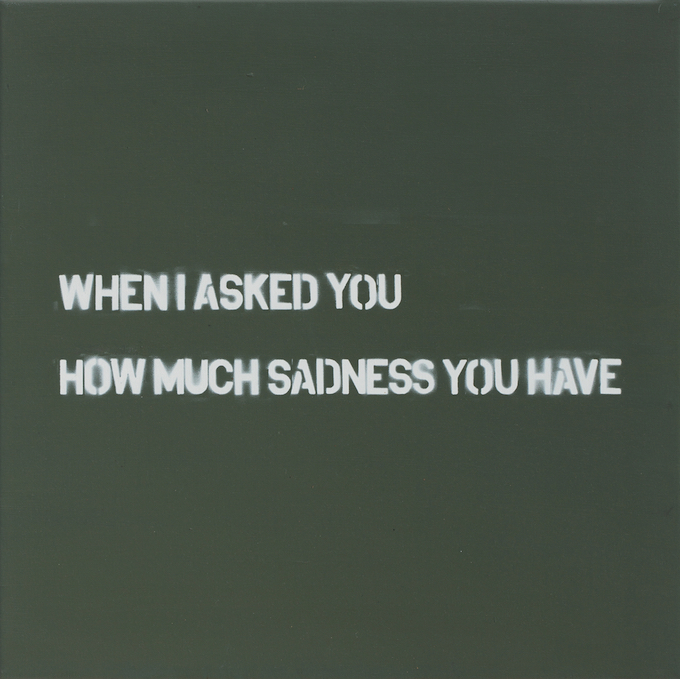

Steve Mumford, Text, 2016. Oil on canvas, 20 x 20 inches. Courtesy of the artist and Postmasters Gallery, New York.