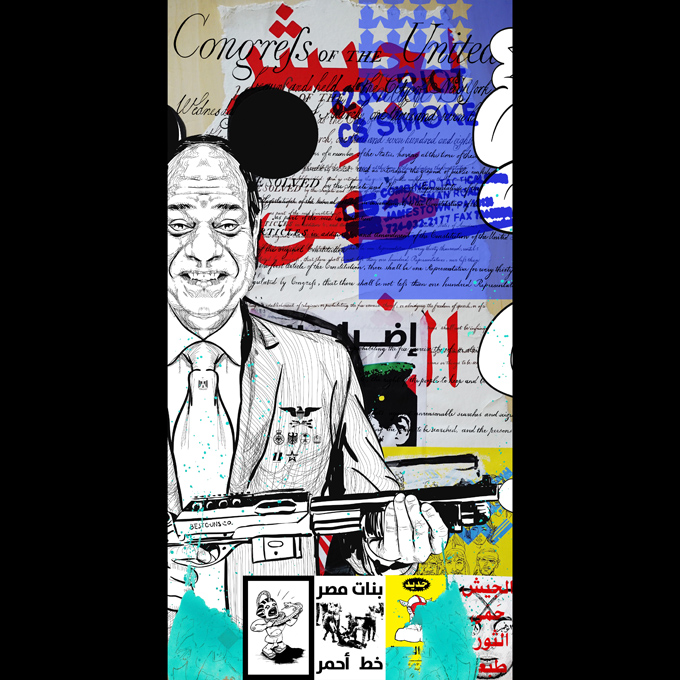

America’s Sisi by Ganzeer, mixed media, 2016.

Five years ago this month, thousands of Egyptians filled Tahrir Square and ignited a mass uprising that lasted 18 days and drove strongman president Hosni Mubarak from office. It seemed to augur a bright future for freedom and democracy in Egypt—but five years, multiple referendums, two parliaments, two presidents, and scores of dead bodies later, Egypt’s present looks just like its past. Egyptian president Abdel Fattah el-Sisi’s crackdown on dissidents spreads: at the end of last year the Interior Ministry raided cultural institutions, including a publishing house and art gallery. Sisi, as well as his minister of religious endowment, have both warned citizens against taking to the streets on the January 25 anniversary. Yet nobody—at least not in the White House—seems to care.

There’s plenty of political repression in Egypt as well—the kind the U.S. is quick to censure when it takes place in China, Russia or Iran.

Even before assuming office, Sisi was already responsible for an estimated death toll of at least 817 during the brutal clearing of a peaceful sit-in in Rabaa Square on August 14, 2013. And under his administration the Egyptian Armed Forces’ operations in Sinai have reportedly killed more than 2,000 people so far, including an unknown number of civilians (the Egyptian government acknowledges virtually no civilian deaths). The Egyptian people are so disillusioned that hardly anyone showed up to vote in the most recent parliamentary elections. Not even fatwas could get people to the polls—and why should they vote, when Sisi’s actions have made it clear that their votes do not matter? But none of that is stopping the United States from supporting him.

In March President Obama lifted a military funding freeze, making Egypt once again the recipient of the second largest U.S. foreign military aid package (Israel receives the largest package). Following the unfreeze, Egypt received 10 Apache helicopters from the United States. One such helicopter was used to conduct a mistaken aerial attack on a tourist convoy in Egypt’s Western Desert that killed 12 civilians, including eight Mexican tourists. Had they been American tourists, perhaps someone in the White House would have cared.

There’s plenty of political repression in Egypt as well—the kind the U.S. is quick to censure when it takes place in China, Russia or Iran. Many of the protestors, secular opposition groups, student groups, and vocal dissidents whose mobilization resulted in the initial jailing of Mubarak are incarcerated in Egyptian prisons, as are journalists; it is estimated that Sisi’s government has arrested 40,000 political prisoners. And while the atrocious conditions of Egyptian prisons have long been the subject of prisoners’ letters, the incarcerated have at least been dealt a better hand than the scores who have mysteriously died while in police custody.

The U.S. tends to posture about democratic values, but its role in Egypt has always belied this position. Not only was Mubarak, Egypt’s dictator for 30 years, backed by the U.S., but under his rule Egypt was a key destination for prisoners transferred by U.S. authorities for torture and interrogation. It is laughable that President Obama calls the U.S. “the envy of the world” when people around the world are suffering because of American hypocrisy. The Egyptian people have experienced this kind of hypocrisy firsthand: when Obama went on television in 2011 to say, “the United States will continue to stand up for the rights of the Egyptian people,” those Egyptians standing up for their rights were simultaneously being hit by tear gas canisters that were proudly marked Made in U.S.A.

This piece, commissioned by Creative Time Reports, has also been published in Salon.