Anahita Razmi, Anahita Razmi Promo on TV Persia, 2014.

The media landscape in Iran is a paradoxical one. Freedom of the press remains a far-off wish, while the Internet is largely censored and—even worse—speed limited. The country’s only legal television broadcaster, Islamic Republic of Iran Broadcasting (IRIB), is a large state-owned network whose director is appointed by the supreme leader. While there are ongoing struggles between hard-liners and more moderate factions of the Islamic Republic’s rulers, IRIB’s programming remains far from independent and has undergone only superficial transformations to more modern and open forms of news and entertainment over the years. Yet within this highly regulated context, satellite TV has come to occupy a unique position. Officially illegal to watch, it is nonetheless widely popular. Unofficial figures state that up to 60 percent of Iranian citizens watch satellite TV. Dishes are to be found on almost every roof. Although official state campaigns have been waged to take down and destroy satellite dishes, an extensive black market ensures that dishes are installed much faster than they are destroyed.

Video still from TV Persia commercial footage. Courtesy of Anahita Razmi.

This sphere of illicit media consumption provides the backdrop for my video-based artwork Anahita Razmi Promo. This work borrows its concept from Chris Burden Promo by the American artist Chris Burden, who died of melanoma earlier this month. Originally shown in 1976 during commercial breaks on American TV channels, Burden’s work comprises a sequence of names of famous artists in bold graphics: “LEONARDO DA VINCI,” “MICHELANGELO,” “REMBRANDT,” “PABLO PICASSO”—and then “CHRIS BURDEN.” The list of names is followed by the disclaimer “paid for by Chris Burden—artist.” With Anahita Razmi Promo, I am repeating Burden’s work under different circumstances, transposing it to a radically different media landscape. My own clip aired in autumn 2014 during regular commercial breaks on a selection of Iranian satellite TV channels. In place of the names listed by Burden, my work presents the names of famous Iranian artists: “REZA ABBASI,” “SHIRIN NESHAT,” “KAMAL-OL-MOLK,” “PARVIZ TANAVOLI,” “ABBAS KIAROSTAMI”—and finally “ANAHITA RAZMI” and “paid for by Anahita Razmi—artist.”

The channels that I contacted about airing Anahita Razmi Promo are Iranian channels but do not actually broadcast from Iran. Operating from Los Angeles, London or Dubai, they constitute in-between media spaces connecting Iran with the country’s diaspora and providing alternatives to Iran’s state-controlled TV channels. Iranians who watch satellite TV have access to a large selection of international programming, including an array of Farsi-language channels. In addition to providing an alternative to state-controlled information, satellite channels offer a means to enjoy officially banned entertainment. They also provide an important platform of expression for the many voices opposed to Iran’s political system.

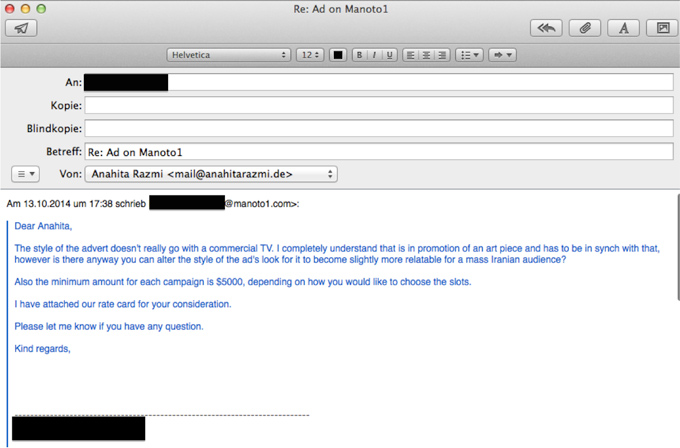

Screenshot of an email from a Farsi language TV channel. Courtesy of Anahita Razmi.

I contacted a number of the more popular channels about broadcasting Anahita Razmi Promo. While some of them rejected the request, struggling with the somehow impalpable commercial intention of the clip, the channels TV Persia and Andisheh TV aired Anahita Razmi Promo 26 times in total during prime-time viewing hours.

Dubai-based TV Persia is home to “Next Persian Star,” the popular Iranian version of “American Idol.” Andisheh TV, a channel airing from California, combines DIY political analysis with shows predominantly made for the Iranian diaspora in the United States. During commercial breaks on these channels, one finds ads from Iranian matchmaking agencies, Iranian retirement homes and expensive perfume companies, along with teasers for imported soap operas and pop music videos. These commercials offer glimpses of the sorts of realities that the preaching authorities of the Islamic Republic disdain: easy entertainment, capitalism, gharbzadegi (or “weststruckness”), lifestyles disconnected from religion.

The power of these media within Iran could be seen last November, when massive crowds flooded the streets following the death of the pop singer Morteza Pashaei. Pashaei died of cancer when he was just 30 years old. His songs were largely banned from state media for being “too romantic.” Yet thanks in part to satellite TV, they still managed to make their way into the hearts of a mass audience. While media inside and outside Iran—and even many of those attending the gatherings—mostly denied that the events were linked to politics, I cannot avoid seeing them as such. While the death of the high-ranking cleric Ayatollah Mohammad-Reza Mahdavi Kani just a few weeks earlier did not elicit public outpourings of grief, the funeral of Pashaei completely incapacitated buzzing Tehran.

Anahita Razmi, Anahita Razmi Promo on Andisheh TV, 2014.

By appropriating Burden’s promo within this complex cultural and political context, my work transforms the original parameters of the piece. Whereas the artists Burden lists are all drawn from the easily recognizable canon of Western art, the Iranian artists I have chosen for my work are a disparate group: some are celebrated within Iran, others are banned or living in exile, but all of them are part of the strange history of Iranian art, a history lacking any popularly accepted canon. Shirin Neshat may be one of the most famous contemporary Iranian artists outside Iran, but the influence of the Iranian censors means that she lives and works in exile. By stealing from Chris Burden and paying people outside Iran to show my video to people inside the country, I am at once affirming the scattered nature of this history and claiming my place within it. I am sneaking in in a double sense: I was born and raised outside Iran, and I continue to reside outside the country. Half of my blood is Iranian, but as I don’t believe in blood ties, my “Iranianness” needs to be promoted to exist. In this sense Anahita Razmi Promo might be seen as an infiltration in a manifold sense, one that lays claim to a piece of my cultural identity while transgressing national, commercial and cultural-historical barriers.