The ancient City of Ani, located in the east of Turkey, near the Armenian border. Photo by Hakan Topal, 2010.

Grasping the Void

Mount Ararat, in Eastern Turkey, on the borders of Armenia, Iran and the Nakhchivan Autonomous Republic, is believed to be the site where Noah’s Ark came to rest. Since the early 19th century it has captured the imaginations of explorers and researchers convinced that the remains of the ark can be found on the mountain. Visible from the Armenian capital of Yerevan and located within the region where Armenians once lived, Ararat holds a special place in the Armenian national imagination as a reminder of the lost homeland.

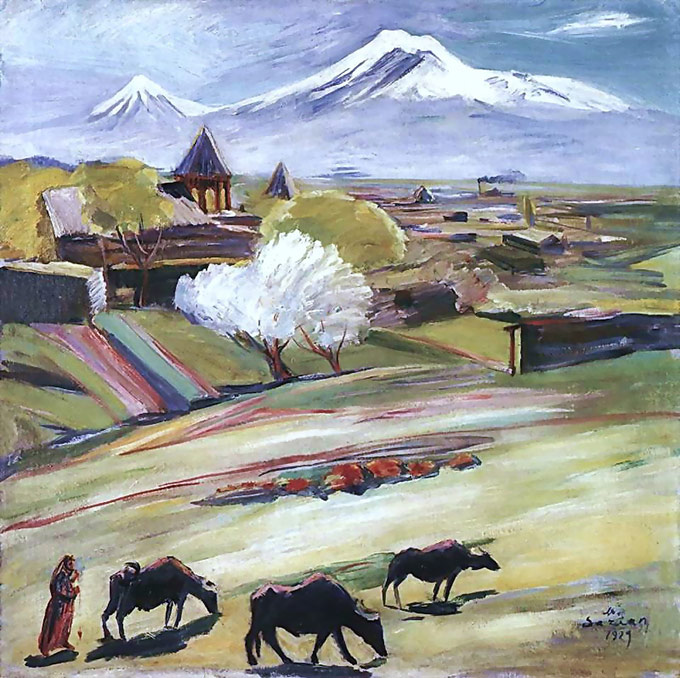

Among the many artworks that have focused on Ararat, the paintings of the Soviet-Armenian artist Martiros Saryan (1880–1972), who obsessively painted the mountain throughout his life, are especially noteworthy. In addition to depicting Ararat itself, Saryan’s works evocatively portray the forests, towns and farmlands that surround the mountain. These landscape paintings are highly personal. Although raised in southern Russia and educated in Moscow, Saryan traveled to Anatolia and the Middle East between 1910 and 1913 and worked in Armenian refugee camps after the “great catastrophe” of 1915: the massacre and displacement of more than one million Armenians by Ottoman Turks amid the upheaval of World War I. The artist’s intimate knowledge of both the land and the unimaginable acts of cruelty that took place there are bound up with his depictions of the crime scene, which is nowadays a highly politicized geographic and ecological terrain. In Saryan’s paintings, a sense of sadness seems to dim even the most joyful colors.

Martiros Saryan, Spring Day, 1929

April 24, 2015, is the 100th anniversary of the Armenian genocide. Alongside my work on the archaeology, history and contemporary politics of the Anatolian and Mesopotamian regions, I have been looking at Saryan’s Ararat paintings, which seem more haunting than ever today, as I reflect on the horrific events of 1915. I believe that acknowledging all the cultures in the Anatolian lands and grasping the void that was left in the wake of the Armenians’ decimation requires a poetic approach. As a Turkish citizen I have a sense of obligation to recognize the sorrowful silence that Saryan’s paintings so powerfully make manifest, especially in a nationalist context in which facing historical facts frequently becomes a politically charged matter.

A State of Denial

Denying the Ottoman Empire’s involvement in the massacre of the Armenian people has been Turkey’s policy since the mid-1960s, when Armenians first began to describe the events as genocide. This is not a simple terminological issue but rather a systematic dismissal of wrongdoing, as it is argued that the civilians who were killed were merely war casualties and not victims of a deliberate effort to eradicate the Armenian cultural group. This year’s anniversary of the genocide might have provided an opportunity for Turkey to face its specters at the national level. Unfortunately it has already rejected this opportunity.

In Turkey, a violent apparatus ensures that the dissenting voices of already disempowered communities are silenced and contained.

When Armenian president Serzh Sarksyan invited Turkey’s president, Recep Tayyip Erdogan, to the events marking the anniversary, Erdogan, instead of providing an answer, chose to mobilize a counternarrative to dilute the importance of the genocide commemorations. His response was to invite his Armenian counterpart, along with many other world leaders, to the centenary of the Gallipoli campaign of World War I, to be held not on April 25, a day traditionally associated with the campaign, but on April 24, the day marking the Armenian genocide. The Gallipoli campaign, which pitted the British Empire and France against Germany and the Ottoman Empire, is an integral part of the nation-building narrative not only of the Turkish Republic but also of many young nations, including Australia and New Zealand. Erdogan’s strategy was to exploit international interest in the event, creating as much noise as possible and thereby impeding the possibility for reflection on the tragic events that took place 100 years ago.

It is not surprising to see Erdogan employing this underhanded political strategy. Every time his Islamist government has faced a political impasse, it has utilized smoke screens, at times bluntly fabricating deceptions in order to sideline the political consequences of state crimes. For instance, when Turkish warplanes bombed and killed 34 Turkish citizens in Roboski, on the Iraq border, in December 2011, instead of opening an independent investigation, Erdogan began attacking his critics. He then tried to cloud the issue by shamelessly likening the incident to women undergoing abortions, which he argued is an equal but less criticized crime.

How can one conceive of a “homeland” in a manner that is inclusive of the overlapping ownership claims of Armenians, Kurds, Turks, Arabs and Assyrians?

The Armenian genocide is an important historical event that Turkey needs to face honestly. But the task of scrutinizing crimes committed by the state is exceedingly difficult, since the traces of these events have been intentionally erased from public memory and discourse. Within Turkey the subject of the genocide is still largely taboo. It is definitely not an easy subject to bring up in conversation, especially given that only 9 percent of Turkish citizens believe that the republic should recognize the massacre as a genocide, according to a recent poll. Moreover, any effort that is seen as “degrading the Turkish nation” is deemed punishable under Article 301 of the Turkish penal code, a legal framework that the European Commission found “fails to provide sufficient guarantees for exercising freedom of expression.” Nationalists routinely threaten writers who dare to speak about the possibility of reconciliation. When Ogün Samast, a 17-year-old Turkish nationalist, murdered the Armenian-Turkish journalist Hrant Dink in January 2007, he was subsequently treated with respect by the Turkish police and given a Turkish flag for a photo op with officers. Over the last seven years the state has handled Dink’s murder as an isolated case and has been reluctant to seek out the underlying nationalist terror network of which Samast was a part.

Ironically, state representatives have been quick to cite “freedom of expression” when it comes to those propagating genocide denial. Take, for example, a recent European Court of Human Rights (ECHR) case pitting the world-famous human rights lawyer Amal Clooney against ultranationalist Armenian genocide denier Doğu Perinçek. At the trial, Perinçek had a team of flag-waving supporters that uncharacteristically brought together Islamists, nationalists and social democrats for the national cause. In a ruling that many in the human rights community decried, the court found that Perinçek is indeed entitled to disseminate his detestable views. To make matters worse, Perinçek’s denialist Talaat Pasha Committee went on to distort this ruling, claiming that the ECHR had confirmed that the Armenian genocide is a lie.

xurban_collective, Mount Ararat, from the research project “The Containment Contained,” 2003.

In Turkey, a violent apparatus ensures that the dissenting voices of already disempowered communities—which include not just Armenians but also Kurds, Alevis and other ethnic minorities—are silenced and contained. Amid this grim sociopolitical landscape, any inquiry into the Armenian genocide on the part of an artist or concerned group requires extreme care and attention. When alluding to state crimes in venues appealing to Turkish people, who are sensitive about the term “genocide” and have been conditioned to reject it, less confrontational language may need to be used while retaining the underlying account and historical importance of the genocide. Yet it is important for artists and writers to continue to try to shift the national discourse on crimes of the past. Equally crucial is the effort to envision a future for the entire region that is less influenced by the rhetoric of nationalism and religious sectarianism. In my view this involves deconstructing, reformulating and reimagining conventional notions of the “homeland,” ancestral belonging and property rights.

A New Homeland is Possible

When we look at the Anatolian and Mesopotamian territory, we find the cultural, religious, urban and historical traces of numerous people who for the most part were erased or appropriated by the Kurdish and Turkish populations that moved to towns left vacant after the exodus of Ottoman Armenians. This ethno-cultural layering makes the question of territorial entitlement especially difficult and complex. Finding forms of restitution and reinstating the property rights of displaced populations without actually dislocating the current residents is extremely difficult. So how can one conceive of a “homeland” in a manner that is inclusive of the overlapping ownership claims of Armenians, Kurds, Turks, Arabs and Assyrians? Can the idea of “homeland” allow for a multilayered interpretation that remains in flux? And can we, moreover, include within that interpretation an ecological dimension that extends to the native plant species and animals so beautifully represented in Saryan’s landscape paintings? If one considers the geologic and ecological context of the lands surrounding Mount Ararat over billions of years, claims of territorial belonging begin to seem less significant. To resolve long-standing disputes over the land in this region, it is therefore necessary to envision less anthropocentric definitions of “homeland.”

The injustices that the Armenian people have endured, from the 1915 genocide to its ongoing denial, necessitate an honest and steadfast reconciliation process. Armenia, the Armenian diaspora and the Turkish Republic need to establish committees of reconciliation to heal old wounds. As happened in post–World War II Europe, we need to envision and implement large-scale social and educational programs to face grim histories and establish efforts to protect cultural heritage and ecology by “communizing” geographic sites that belong to all.