View of Smara, one of the Sahrawi refugee camps in Tindouf, Algeria. Photo by Mel Chin, 2011.

The HSBC ads at Newark International Airport could not have been more appropriate for my trek to the Sahrawi refugee camps in Tindouf, Algeria. As I ambled through the jet bridge with my carry-on, color-coordinated images of demure North African women met my eyes, accompanied by some facts assembled by the bank—“0.3% of Saharan solar energy could power Europe”—and a self-aggrandizing but, for me, prescient message: “Do you see a world of potential? We do.”

It was the fall of 2011, and I was on a string of flights from North Carolina to Algeria to participate in an ARTifariti convening of international artists presenting human rights–related projects at the Algerian camps and in Western Sahara. During previous gatherings, a New York–based art critic had presented a slide show to international artists and Sahrawi refugees, sharing pieces by activist artists and filmmakers such as Ai Weiwei and Spike Lee. The get-togethers offered a forum to consider artists who might do a project in the camps. And in the end, the refugees had chosen a Chinese Texan who had spearheaded Operation Paydirt’s Fundred Dollar Bill Project, an artwork that prompted Americans to draw their own versions of $100 bills (in order to raise awareness of and prevent childhood lead poisoning). Essentially they said, “Bring us the guy with the money.” So I packed my bags and left for the western lands of North Africa.

Tatiana Shelton in the “Safehouse” of the Operation Paydirt’s Fundred Dollar Bill Project in St. Roch, New Orleans. Photo by Amanda Wiles, 2009.

At an unknown hour on a starless night, I arrived in the 27 February Camp—one of Algeria’s five Sahrawi refugee camps (named after the date in 1976 on which the Polisario Front declared the birth of the Sahrawi Democratic Arab Republic)—and was led to the home of our host, Abderrahman. As we entered his compound, the seasoned warrior, dressed in a blue darrâa, emerged from a UN tent, unfurled a carpet over the sand, ignited charcoal and began to prepare the customary tea for us. We attempted to translate from Hassaniya Arabic to Spanish to English over tea, getting a taste of enthusiastic nomad hospitality.

That night I heard firsthand the history of the Sahrawi people, who today are divided between Algerian refugee camps and a sliver of Moroccan-occupied Western Sahara that they call the “liberated territories.” For nearly four decades, warfare and political powers have trapped more than 150,000 Sahrawis in the camps and separated them from their family members in the liberated territories, which are bounded by the Moroccan wall to the west and Algeria’s border to the east. When Morocco and Mauritania invaded Western Sahara in 1975 (Mauritania withdrew in 1979), they split up the land and seized the Sahrawis’ natural resources—water, rich fishing grounds and the world’s largest phosphate mine. Now, inhabiting either the arid, landlocked region of Western Sahara or the bare-bones camps of Algeria, the Sahrawi people depend entirely on international humanitarian aid for food, water and medicine. And while Western Sahara has none of the lead-poisoning problems of postindustrial America, its liberated territories have more landmines than any other place on the planet.

In the tent of Abderrahman and his family. Photo courtesy of Mel Chin, 2011.

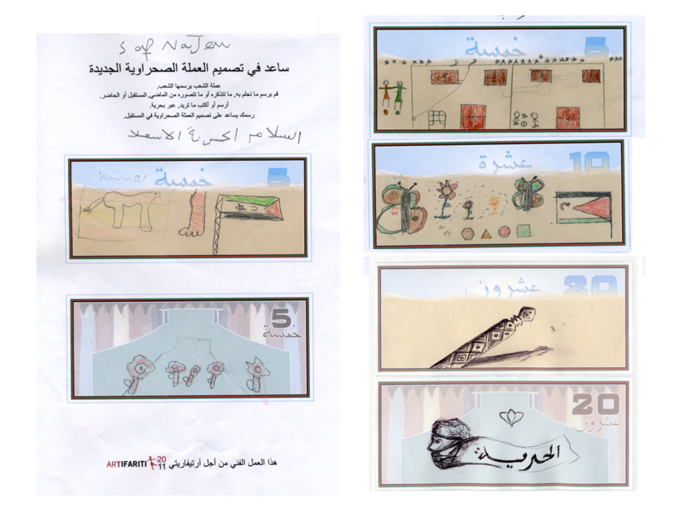

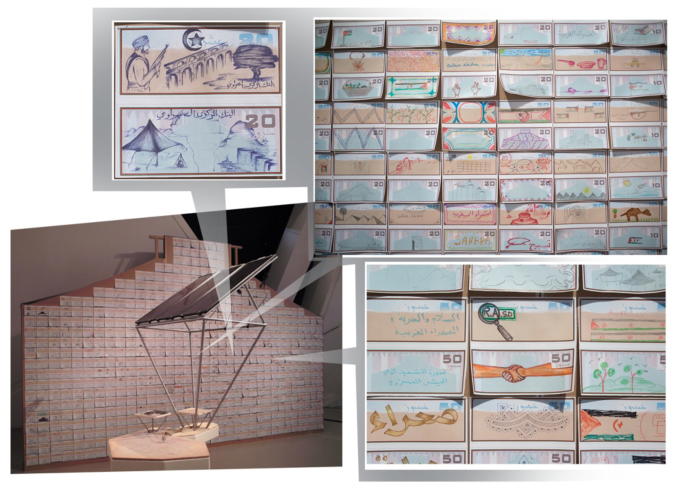

In the morning I awoke from this harrowing chronicle in a land of sand and rock that was brutally burnished by the sun—and I can guarantee that there was no bank in sight. I soon learned why the Sahrawi people were so interested in the Fundred Dollar Bill project: they have no currency of their own and deal mostly with Algerian dinars. In response, we created a background template for their currency, printed thousands of blank bills and distributed them through the camps, announcing a design opportunity. After we curated their drawings, the Sahrawis would vote on the designs for what might become their first currency.

The denominations for the currency, called “sollars,” were 5, 10, 20, 50 and 100. Children and teens drew the 5s and 10s; young adults, the 20s; and of course, the elders, the 100s. But the designs for the 50s would have two adult versions, one male and one female. The survivalist family culture that has emerged from the hostile desert climate has enforced a long-standing code of equality between the sexes. In a region where food is scarce and hot summer temperatures and freezing desert nights can kill, whoever survives the elements must be allowed equal rights in the tribe to barter and represent the family, regardless of religious dictates.

The children’s school at the 27 February Camp. Photo by Mel Chin, 2011.

Submissions for the “Sollar” currency design competition. Photo courtesy of Mel Chin, 2011.

While I was in the camps, I came to understand that the symbolic and therapeutic benefits of designing the first Sahrawi currency with the refugees were not worthy enough goals. The Sahrawi people need a real economy. And to make that happen, the fictional currency I helped the refugees design had to be backed by something real and exchangeable on international markets. As I mulled over the problem under the blazing sun, I realized that the desert holds the potential to bring Sahrawis economic and political independence—and the leverage necessary to help us all combat climate change.

What the world needs now is the first Bank of the Sun.

The first solar energy–backed currency in the world could bring the Sahrawi people an independent economy and offer a major breakthrough in an environmental quagmire. We would create a new model of banking and currency, free from the dominance of gold and oil, for first-world countries to follow. And this model would be delivered by the Sahrawi people, who have been waiting for freedom and self-determination for 39 years! By achieving worldwide renown for freeing people from hydrocarbon dependency, the Sahrawi could then barter with the global community for another form of independence: their right to self-determination.

Freedom is the concept propelling my action with the Sahrawi people. The sun on this poster for the Bank of the Sun is composed of the Arabic word for “freedom,” repeated 38 times—once for every year the Sahrawis have waited for the right to self-determination (as of last year). Poster designed by Mel Chin, 2013.

I admit that it was a pretty far-out and grand idea, but I suppose I did see a world of potential in Saharan solar energy, just like the jetway HSBC ad said. I was thinking like a bank.

After getting back from the Tindouf camps, I found myself in Texas, accepting a national award for my efforts in public art and, most likely, boring everyone with crazy talk about a Bank of the Sun in landmine-laced Western Sahara. My friends were more concerned about my diminishing sense of self-preservation than about anything I said—especially after I told them that my trip to Tifariti had been interrupted by the armed kidnapping of three foreign-aid workers from a neighboring refugee camp. They didn’t even entertain my ideas with any questions about how the bank idea could be pulled off.

As with most such gatherings, there was not much left to do after the award ceremony but drink and dance. So, with friends in tow, we honky-tonked through San Antonio, taking over a bar by the River Walk and proceeding to do what had to be done. While taking a break from the floor, I noticed a man about my age sitting at a table with a beer, tapping his feet to the bluesy beat. I had my posse pull him onto the floor. He began to move in a calculated way, like an engineer. Intrigued, I joined him and the party on the floor.

Over the din, I shouted, “What do you do?”

He shouted back, “I’m an engineer.”

“Really?” I asked. “What kind?”

“A solar engineer.”

I challenged Texas style: “So, ever heard of Western Sahara?”

Matter-of-factly he replied, “Yes, we designed a power station for the refugee camps there.”

For me, a light flicked on, burning away the haze of booze and turning the blaring R&B into a background of sweet birds; the bodies in frantic motion seemed to stand still. I urged him off the dance floor. He told me, in an Australian accent, that he was Dr. Richard Corkish, head of photovoltaic engineering at the University of New South Wales in Australia. Not only that—his colleague had just been in the same refugee camps I had visited, advising on how to power a women’s clinic. It was a profound coincidence, to say the least. We closed the bar, and I left clutching Dr. Corkish’s business card.

Installation view of The Potential Project for “Climate is Culture” at the Royal Ontario Museum, Toronto, Canada. Photo by Susana Resiman, 2014.

Since our night on the floor, Dr. Corkish has been an adviser to the Bank of the Sun, which is on its way to becoming a reality. He has assigned students the project as part of his curriculum and counseled us on the design of a modular, pragmatic stand-alone solar power plant in Western Sahara, as well as a cost-effective method for transmitting power. Following Corkish’s methodologies, we could generate more than enough energy for Sahrawi needs, creating a surplus to sell to neighboring countries or even to Europe. By working in the Western Sahara to retool our approach to energy, we would prove that the most advanced methods of solar-power storage and delivery are feasible even in a place with no infrastructure. The most appropriate technology for us all could be built from the sand up.

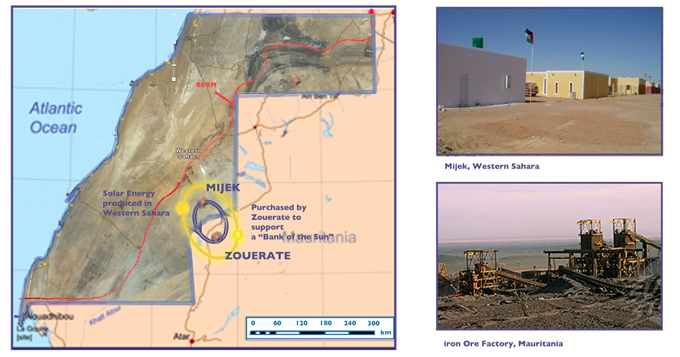

In February 2013 I discussed the project with Ahmad Bukhari, the Polisario representative to the United Nations, and later with Mohamed Yeslem Beisat, the ambassador to the United States for the Western Saharan people. Skeptical at first, they have both become advisers and creative collaborators. To make the first Bank of the Sun a reality, we have to find a place where electricity can be generated that is both safe from armed conflict and close enough to someone interested in buying energy. Bukhari suggested placing the stand-alone solar power plant not in the camps but in Mijek, a nomadic outpost in the liberated territories. Mijek continues to be the most likely site because the energy could be sold to Zouérat, a town in northern Mauritania where an iron ore mine needs more power than is available. The Mauritanian ambassador recently confirmed that the country would buy any energy offered. I have started to seek funds for a fact-finding trek, during which I will finally step on the sands of Western Sahara.

The site and plans for the potential Bank of the Sun. Image by Mel Chin, 2013.

During my time in the Sahrawi refugee camps, I relearned a lesson I picked up in the flood-wracked and environmentally poisoned parts of New Orleans: you are not inspired by tragedy or human suffering—you are compelled. My brilliant translator, a young man named Mohamed Sulaiman Labat, was born in the camps and has never traveled beyond his host country, Algeria, or the shameful wall of sand and explosives erected by Morocco in Western Sahara. Sulaiman is majestic in his capacity for optimism and his aptitude for imagining alternative futures based on ideas we discussed during my stay. On our last night together, he spoke with me about staring each night into the vast sky above the camps. He then asked, “No disrespect, but why is it so easy for an artist to see our need for justice when the rest of the world can’t?” A question like that makes you think about what could be and about how our humanity is challenged if we don’t take action to amplify his question—and to force an answer.

Correction: May 1, 2014

An earlier version of this article misstated the number of Sahrawi refugees living in the camps of Algeria. The number is estimated to be 150,000, not 250,000.

Climate Reports is made possible by the Robert Rauschenberg Foundation. This series is produced in conjunction with the 2013 Marfa Dialogues/NY organized by Ballroom Marfa, the Robert Rauschenberg Foundation and the Public Concern Foundation.