Marina Abramović Institute West Facade rendering ⓒ OMA / Courtesy Marina Abramović Institute

I once met a shepherd in Sicily. Every time I asked him a question, he closed his eyes as he answered me. I asked him why he did this, and he replied, “When I talk, I don’t need to see.”

Multitasking and shortened attention spans have been common subjects of lamentation in the age of the internet and smartphones. We are equipped with time-saving technologies, but somehow we have less and less time. But I believe our society is primed for a counterpoint, especially in the realm of art.

How often do we see people rush past a few works of art in a museum, exit and immediately tweet about what they’ve just seen? Long-durational work, that is, art that elapses over extremely long periods of time, functions as an antidote to that distracted rush, by allowing us to reclaim time as a natural resource in the context of art. This work demands presence, which is required less and less in the digital age. It recalibrates our senses of time, space and self.

Marina Abramović Institute Main Performance Space, first draft rendering ⓒ OMA / Courtesy Marina Abramović Institute

The Artist Is Present was my three-month retrospective performance at New York’s Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in 2010, during which I stared into the eyes of anyone who wished to sit across from me. Close to 1,400 people participated, and many more waited to do so. This demonstrated to me a very strong desire from the public to be still, breathe, make eye contact and exchange energy. I like to think the Sicilian shepherd would have enjoyed it.

After I completed this performance, I was very moved not only by my experience, but also by the public’s enthusiasm for the piece. That’s when I had a vision to create an institute that would be dedicated to long-durational work. While the Marina Abramović Institute (MAI) will be a venue mainly for performance art, it will also host dance, theater, film, music, opera and other art forms, in the context of long-durational work.

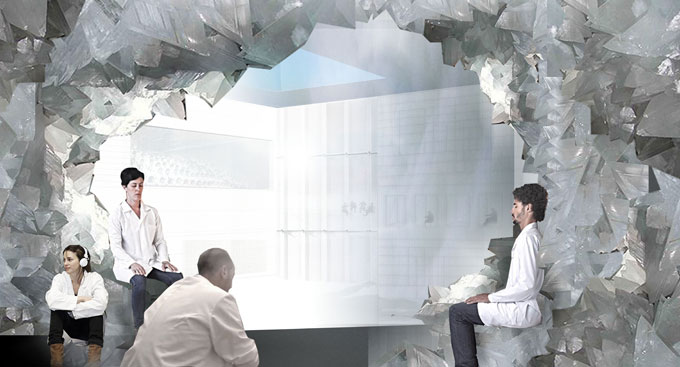

Marina Abramović Institute Crystal Room rendering ⓒ OMA / Courtesy Marina Abramović Institute

Performance art remains a relatively underrepresented art form, despite its recent rise within the art world, and long-durational works are especially rare to see. Few spaces specialize in performances that take place over many hours—let alone days, weeks or months. With residencies at the Institute, artists will have a space to develop and to present this kind of work. It’s a form that needs an audience, and therefore a community. I am so pleased to see performance gaining prominence in the world of art; I needed the audience’s participation and energy to complete my retrospective performance.

For this reason, The Artist Is Present could only have happened at this later stage of my career—not only because performance has never been as widely recognized as it is today but also because I needed to reach a level of physical and mental ability to complete the work. It took 40 years of performance experience and research of other cultures to achieve that state.

I have synthesized this work and research into a series of exercises called the Abramovic Method that I practice myself and teach my students in performance workshops. The exercises are used to test the limits of the mind and body and increase awareness of the present moment.

Marina Abramović, The Abramovic Method, PAC (Padiglione d’Arte Contemporanea), Milan, Italy, 2012 © 24 ORE Cultura S.r.l. and Laura Ferrari. Courtesy Marina Abramović Archives.

One of these exercises is the slow-motion walk: slowly lift one leg, stretch it outward, touch your heel to the ground and move forward. Then repeat. By breaking down the simple activity of walking into these separate parts, and concentrating on each individual motion, we sensitize our bodies and minds to an activity that we usually take for granted. We do one thing 100 percent, instead of 10 things 10 percent.

I’ve come to realize that people from all walks of life, not just performance artists, may benefit from these techniques. The needs of performers in training, and the needs of the broader public yearning for a digital detox, actually coincide. These exercises help us to look inward, a tall task in a world with a million stimuli competing for our attention. I think it’s especially crucial for digital natives to learn these techniques for concentration—doing nothing and entering a silent state.

At MAI, visitors who attend a performance or lecture will be able to practice the Method. They will receive lab coats to create a spirit of experimentation. They will also be given optional noise-canceling headphones, and asked to leave their watches, cellphones and any other electronic devices at the door. The entire experience, including attending a performance, is designed to last a minimum of six hours.

Marina Abramović, The Abramovic Method, PAC (Padiglione d’Arte Contemporanea), Milan, Italy, 2012 © 24 ORE Cultura S.r.l. and Fabrizio Vatieri. Courtesy Marina Abramović Archives.

I would love to see a farmer or a businessperson experimenting with performance art techniques. In this spirit of unlikely juxtapositions, my dream is for MAI to be a place for thinkers of all disciplines to come together and pave new ground.

Throughout my life, I have spent a great deal of time immersing myself in other cultures, like that of Tibetan Buddhists, Australian Aborigines and Brazilian shamans. These experiences have profoundly impacted my own work, and so I know firsthand the value of being open to different modes of thought. I think our specialized sectors of knowledge could benefit from community collaboration and experimentation, in the spirit of the Bauhaus, but even beyond art, into science, spirituality and other fields.

I strongly believe in the powerful possibilities of combining the intuition of artists and spiritualists with the rigors of science and technology: the Abramovic Method plus the scientific method, you could say. Art asks questions, but doesn’t necessarily get answers. So I’m interested in taking the next step and staging a dialogue with top minds in other fields, allowing the varied modes of thinking from different disciplines to enhance one another.

Marina Abramović, The Abramovic Method, PAC (Padiglione d’Arte Contemporanea), Milan, Italy, 2012 © 24 ORE Cultura S.r.l. and Fabrizio Vatieri. Courtesy Marina Abramović Archives.

One example of this kind of interdisciplinary collaboration came on the heels of my MoMA show. After the performance was complete, many scientists approached me, intrigued by the extremely emotional reaction of the individuals sitting across from me. I, too, was curious to know more about the public’s reaction. So I collaborated with neuroscientists on a project called The Magic of Mutual Gaze, which essentially restages The Artist Is Present, but with each participant wearing EEG caps on their heads. Brain waves are displayed in real time, visualizing the moments that the two people are “on the same wavelength.” We’re also working on a brain-powered cart that moves when our brain waves are aligned.

As a performance artist, I have devoted my life to experimentation and discovery through art and interdisciplinary collaboration. I am lucky to be able to work with the brightest minds of not only the art community but scientists and spiritualists as well, who have enriched my work and my life. At MAI, my legacy will not be my artwork, but rather, the opportunity for all to experiment and discover in the same way. I believe the time is ripe for such an opportunity.

In this new century, our experiences are quickened, truncated and virtual. To counteract this often-alienating reality, MAI will be a physical space where we can decelerate and recalibrate our bodies and minds. It is a new and urgent undertaking materializing at a time in history that needs it most.