The top of a mosque moved more than a mile by the 2004 Indian Ocean tsunami, as depicted in a poster displayed at the Aceh Tsunami Museum, Banda Aceh, Indonesia. Photo by Ivan Sigal, 2012.

Last year I visited Banda Aceh, a provincial capital located on the northwestern tip of Sumatra. The Indonesian city was the epicenter of the December 26, 2004, Indian Ocean tsunami, which tore through communities from Thailand all the way to Somalia, killing approximately 230,000 people. While I had traveled to Sri Lanka to help right after the storm, I followed Banda Aceh’s story of recovery closely over the years. I wanted to see for myself the choices a community made in rebuilding and memorializing those lost in the disaster. What I discovered was both haunting and instructive, a monument to a past catastrophe and a harbinger of things to come.

Banda Aceh was substantially rebuilt within five years, although traces of the tsunami remain visible on the margins of the city, in the shape of seawalls and remnants of the old bridge across the bay, and in the continuing home-reconstruction projects at the town’s edges. The province of Aceh, of which Banda Aceh is the capital, also experienced a political transformation; the armed separatist rebellion across Aceh’s interior concluded with a peace deal and substantial regional autonomy. Although international donors provided some $7 billion in funds to aid in the reconstruction, by some accounts it flowed disproportionately to the city at the expense of smaller towns and more remote regions, as well as to the political victors of the conflict. Along with urban and residential reconstruction, the city built memorials, a mass grave and a museum. These spaces preserve the memory of the 160,000 killed by the tsunami in Aceh, but they also play other roles, offering both moral instruction in civic engagement and tsunami tourism.

Diorama depicting Banda Aceh’s Baiturrahman Grand Mosque, Aceh Tsunami Museum, Banda Aceh, Indonesia. Photo by Ivan Sigal, 2012.

Diorama depicting people clinging to roofs, Aceh Tsunami Museum, Banda Aceh, Indonesia, December 2012.

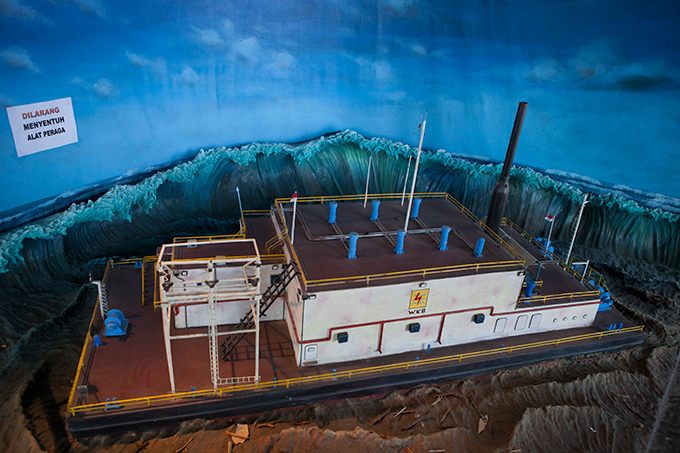

The Aceh Tsunami Museum in particular embodies this goal of civic instruction. Photos of death and destruction, taken after the tsunami, loop endlessly; video monitors play images of traumatic moments, now pixelated and bordered by benign blue-bubble backgrounds. Colorful dioramas restage scenes of terror and death: clay figures hang from model boats or flee massive blue papier-mâché waves. A miniature of the city’s famed Baiturrahman Grand Mosque, one of the few buildings not destroyed by the waves, stands alone in front of a painted screen of rough sea and sky. Rusted motorcycles and seismographs, encased in glass, have been repurposed into objects of reverence and sentiment. Interactive maps depicting the changes in coastline are cast in rough gray fiberglass. A model house built on a hydraulic jack simulates the experience of shaking earth. These objects allow us both to look directly at horror and to distance ourselves from it, through facsimiles reduced in scale, rendered in clay and captured and framed in glass. They keep the experience at a safe remove while providing instruction in the value of creating and preserving order—implicitly supporting the post-conflict state.

New homes customized by their inhabitants, Banda Aceh, Indonisia, Photos by Ivan Sigal, 2012.

Beyond the memorials, Banda Aceh is a rebuilt city, now comprising neighborhoods of identical houses built with aid agency funds and supported by international contractors. Every house has been customized by its owner; variously colored facades, porches, patios and additions provide each with an individual personality. Neighborhoods are now protected by sea walls and acres of mangrove. Here is a city returned to its former pace, an ocean becalmed. Aceh’s story seems to be in the past, but the idea that the disaster it experienced can be confined to symbolic representations in museums is an illusion: the clay figurines drowning in papier-mâché waters are, I fear, projections of our own future.

When I first traveled to Sri Lanka in the days after the tsunami, witnessing the scale of destruction and trying to help in the aftermath changed my life. It opened in me a sense of urgency and an understanding that frequently the scope of disaster is the result of human failure rather than natural catastrophe. After the tsunami came Hurricane Katrina, the Kashmir earthquake, the Haiti earthquake, Superstorm Sandy, Typhoon Haiyan and numerous other calamities. With each of these events, it has become clearer that our efforts to mitigate the destruction unleashed by natural disasters are grossly inadequate. Forecasts of stronger and more frequent storms caused in part by a warming ocean mean that we will have to manage the threat of similar disasters for many years. We are only beginning to recognize what needs to be done, and how vulnerable we become the longer we wait.

Diorama depicting people fleeing a wave, Aceh Tsunami Museum, Banda Aceh, Indonesia. Photo by Ivan Sigal, 2012.

Diorama depicting a floating diesel power station, Aceh Tsunami Museum, Banda Aceh, Indonesia. Photo by Ivan Sigal, 2012.

Diorama depicting people fleeing a wave, Aceh Tsunami Museum, Banda Aceh, Indonesia (detail). Photo by Ivan Sigal, 2012.

Diorama depicting people fleeing a wave, Aceh Tsunami Museum, Banda Aceh, Indonesia (detail). Photo by Ivan Sigal, 2012.

Poster of tsunami victims, displayed at the Aceh Tsunami Museum, Banda Aceh, Indonesia. Photo by Ivan Sigal, 2012.

Foundation for a new home in Banda Aceh, Indonesia. Photo by Ivan Sigal, 2012.

Long-term effects of beach erosion in Banda Aceh, Indonesia. Photo by Ivan Sigal, 2012.

Women sitting by a seawall in Banda Aceh, Indonesia. Photo by Ivan Sigal, 2012.

Remnants of a bridge in Banda Aceh, Indonesia. Photo by Ivan Sigal, 2012.

This piece, commissioned by Creative Time Reports, was also published by Global Voices.