The stage at the Bardo Square sit-in moments before Hamma Hammami, a member of the National Front party, speaks to the crowd, Tunis, Tunisia. Photo by Nadia Ayari, August 24, 2013.

To readers unfamiliar with conventions used for text messages and online chatting in Arabic: please note that the number 9 refers to the phonetic sound of the letter Qāf (ق). Additionally, 3 refers to Ayin (ع) and 7 to Hā (ه).

“Hani 9oddem el UIB,” says Sarah Zaafrani, a 33-year-old Tunisian lawyer speaking to her friend on a cell phone. “I’m in front of the UIB [Union Internationale de Banques or International Union of Banks].” She is coordinating with fellow protesters who are attending an August 24 rally as part of the continued sit-in outside Tunisia’s National Constituent Assembly (or ANC, its common French acronym) in Bardo Square, in the nation’s capital, Tunis. The sit-in began in late July as a response to the assassination of Mohamed Brahmi, a leader of Tunisia’s socialist Popular Front. Like many, Zaafrani has chosen the sidewalk in front of the International Union of Banks as a gathering point. She is certain her friend will know the spot. It is so iconic that the statement she just uttered is the title of a popular Facebook page that regularly posts updates on the protest.

Days earlier, Zaafrani had expressed her skepticism of the Bardo Square sit-in, a sentiment shared by many in her community: “I think the opposition’s demands are off-putting. They are asking for the dissolution of the appointed government and the elected ANC. I know these goals are up for negotiation, but it seems to me too much to ask for at once. The country is stuck and we need things to move fast.” Zaafrani lives with her son in El Menzah VI, a middle-class neighborhood in Tunis. She rents an apartment not far from the one in which she grew up. Recently divorced, she supplements the income she earns from her new law practice by teaching at the local law school. She is well traveled, casually dressed and speaks impeccable French. When asked about her religious beliefs, she answers, paraphrasing Khalil Gibran’s The Prophet: “Our daily lives are our temples and our religion.”

Sarah Zaafrani (right foreground) gathering with fellow protesters at Bardo Square, Tunis, Tunisia, with the National Constituent Assembly in the distance. Photo by Nadia Ayari, August 24, 2013.

Since the fall of Zine Abidine Ben Ali’s regime in 2011, this small North African country has experienced a deepening economic crisis and unprecedented cultural divisions, both of which have led to widespread political discontent. Many Tunisians, mainly urbanites like Zaafrani, were distressed by but accepting of the October 2011 election results. Ennahda, a self-proclaimed moderate Islamic group, won by securing 89 seats in the 217-member parliament. Ennahda supporters coined the phrase sfir facil sfir (“zero point zero”) to refer to the anticipated percentage of opposition voters. The losing parties, making light of their new marginalized status, appropriated the expression for themselves and used it sarcastically when they turned out in impressive numbers to anti-Ennahda protests.

“What is most frustrating is that the people in power today were not present at the revolution. It was a populist uprising motivated by socio-economic factors, not religious ones,” says Zaafrani. In fact, most Ennahda leaders were either in prison or in exile during the ousting of the former president. Members of the Ennahda movement had been brutally prosecuted for their religious practices and political ambitions during Ben Ali’s nearly 25-year rule. “In the ‘90s women were harassed for wearing super-long skirts and men were stopped for sporting beards. Today, the norm has completely shifted. Storeowners tell me to cover up while I am shopping for groceries,” she continues.

Alarm escalated over the course of the year following Ben Ali’s January 2011 overthrow. In early March 2012, a group of Salafis—an ultra-conservative faction of Sunni Muslims—protesting at Manouba University replaced the campus’s national flag with the Salafi flag. The incident followed the announcement from the university, one of the largest in Tunisia, that it would continue its classroom ban on full-faced veils. When authorities did not intervene and instead blamed the school’s dean, who had been physically attacked in his office by some Salafis, of mishandling the matter, many Tunisians found their fears confirmed. The new government would not protect secular civilian life.

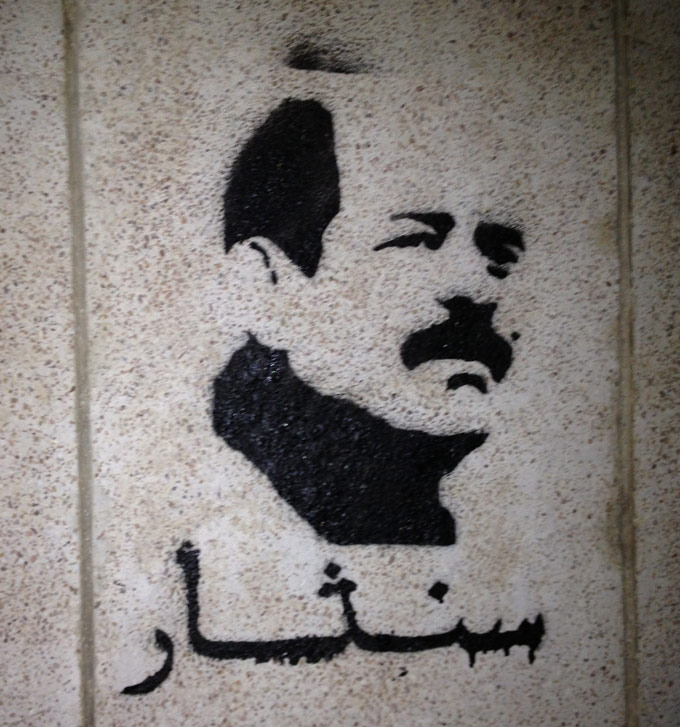

A graffiti portrait of Chokri Belaïd, the lawyer and opposition leader assassinated in February 2013, with the words “we will revolt” stenciled under it. Photo by Nadia Ayari, Tunis, Tunisia, 2013.

Belaïd: “The issue is that there is a place for them [Islamists] in our plan but there is no place for us in theirs.”

In the year and a half following the university incident, cultural divides widened. The abuses of the Leagues for the Protection of the Revolution

(a vigilante group with ties to Ennahda); the unsubstantiated arrests of journalists, artists and social-media activists and the February 2013 assassination of the left-secular politician Chokri Belaïd, who was well known for his fervent criticism of the Ennahda government, galvanized the diverse opposition and its supporters. Most of them accused the Islamist party of ordering the killing. Still the opposition’s major parties—Nidaa Tounis, Al Joumhouri and the Popular Front—as well as its smaller groups and independent politicians could not reach a consensus on what to do next and many citizens started to wish the thawra (“revolution”) had never taken place. But when on July 25 people took to the streets in large numbers to protest the killing of Brahmi, the opposition decided to come together and mobilize as one.

The resulting sit-in has found traction, gathering hundreds of thousands of protesters. It has also been met with criticism. Ennahda supporters fault the i3tisam (sit-in) for representing the values of the old regime and the interests of the elite. They claim that the opposition has been impairing the Troika—the coalition established by three of the parties elected to the ANC after the revolution (Ennahda, Ettaktol and the Congress for the Republic)—by boycotting official orders across all levels of government. When asked about the urgency with which the organizers have been handling the sit-in, Zaafrani points to its blunt official name: I3tisam El Rah7il (“The Departure Sit-In”). She explains that with the risk of violence on academic campuses as they open across the country this month, it is imperative that negotiations between the Ennahda-led government and the opposition begin as soon as possible. “I feel the country is divided like never before. We have always been a diverse community, Carthaginians in Rome. Today, that history is in danger.”

An advertisement promoting diversity, part of a campaign funded by the Tunisian Union for Advertising Agencies and a few private institutions. Photo by Nadia Ayari, 2013.

“Diversity” (Ikhtilaf) is a word significant to Tunisian vernacular of late. Its ideological and socio-economic implications are the subject of a large advertising campaign funded by the Tunisian Union for Advertising Agencies and a few private institutions. One of its taglines is, “Diverse but always united.” Another banner states, “There is no loyalty but to Tunisia.” However, believing in unity and patriotism is challenging these days, especially for Zaafrani. As a young divorced mother, she is directly affected by the country’s economic and cultural woes. She is experiencing a sense of loss and fears the new trends toward repression and violence will continue for some time. Convinced Tunisia will become another Islamic regime, she quotes the late Belaïd: “The issue is that there is a place for them [Islamists] in our plan but there is no place for us in theirs.” Belaïd, an eloquent and charismatic speaker, was an unrelenting advocate for peaceful protests and it is his legacy that protesters at Bardo Square have upheld so far.

Tonight the atmosphere at Bardo is buoyant. Protesters of all ages assemble, young women and men hand out colorful flyers and Pink Floyd’s The Wall blares from a set of loudspeakers. A white ice cream truck parked in front of the UIB is marked in black paint. It reads, Glace el I3tisam or “Sit-in Ice cream.” As Zaafrani walks by it, a familiar political chant swells from the crowd: 7al el 7okoma / wajib! (“The dissolution of the government / is a duty!”). “The dissolution of the assembly / is a duty!” she joins in. Yet, despite her singing, Zaafrani does not agree that the ANC should disband.

A “Sit-in Ice Cream” truck parked in front of the UIB [Union International de Banques] in Bardo Square. Photo by Nadia Ayari, August 24, 2013.

Many Tunisians find the opposition’s proposal to dissolve the ANC, which was elected to devise a new constitution in October 2011, unrealistic. The opposition hopes to pressure Ennahda members to consent to the termination of the current government and its replacement with a temporary, non-partisan expert committee. This committee would run the country until the new constitution is ratified, and then oversee the first head-of-state elections since the former dictatorship. But even with Ennahda’s popularity at its lowest since it was voted into parliament, it is unlikely the party will relinquish power.

Two and a half years into a transitional government, Tunisians of all backgrounds wake up wondering what is next.

Other proponents of the opposition believe a clean slate is necessary. They cite the delay past an agreed-upon one-year mandate and corruption as the main reasons to consider the constitution’s current draft invalid. Since Brahmi—who was a constituent of the ANC—was killed, over 60 assemblymen and woman have frozen their memberships. In turn, the assembly’s activities have been officially suspended since August 6, and the constitution, rumored to be in its final stages since July, remains untouched. Widely regarded as political sabotage, Brahmi’s assassination is suspected to have been planned by a faction other than Ennahda. Whoever is responsible for the murder has successfully put the country on hold.

Weeklong talks between Ennahda and the opposition seem to be going nowhere. Reports on the negotiations, mediated by the Tunisian General Labor Union (UGTT) and the Tunisian Union for Industry, Commerce and Handicraft (UTICA), are abstract but reflect the country’s polarization, suggesting each side’s unwillingness to make concessions. Zaafrani sighs, “It feels like we are losing ground.” Indeed, with each passing rally, the sit-in’s attendance has diminished. The turnout on September 7, commemorating Brahmi’s arb3een (the fortieth day since his death) was estimated in the tens of thousands. This is a decline from August 6, the six-month anniversary of Belaïd’s death, when as many as 100,000 or more demonstrators packed the two-kilometer stretch of streets from Bardo Square to Bab Saadoune to commemorate both Belaïd and Brahmi.

At the same time, Ennahda is falling out of favor with its own base. As most Tunisians watch their businesses suffer and their country sink into civic disarray, a considerable number of them have started to regret their 2011 Ennahda vote. Lately, the ruling Islamist party appears busy; calibrating its next moves, fearing it may meet the same fate as Egypt’s Muslim Brotherhood. And yet the opposition idles, unable to articulate a persuasive position to convert disenchanted Ennahda voters.

As she gets in her car to head home from the rally, Zaafrani remembers breaking into tears when driving past a statue of Habib Bourguiba, who fought for Tunisia’s independence from France and served as the country’s first president from 1957 to 1987. “It happened last year. My kid, who was in the back seat, got so upset when he saw me sobbing. It was hard to explain to him.” But last year feels like a lifetime ago, before the public assassinations and current deadlock. Today, two and a half years into a transitional government, Tunisians of all backgrounds wake up wondering what is next. While they do not share the same views on how to resolve the crisis, they agree on this: no matter what the future of Tunisia is, it is taking a very long time to get there.