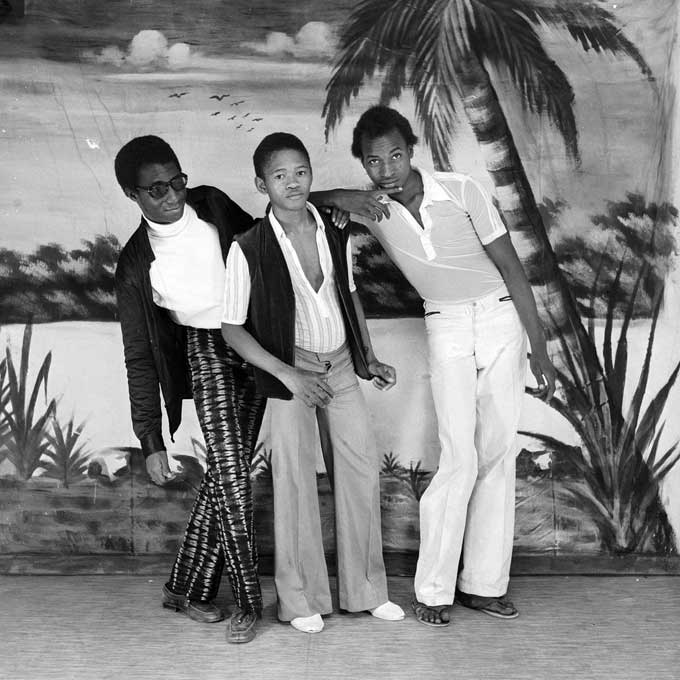

Adama Kouyaté, Les trois amis, 1971.

The entire studio fits in a small room, just over 40 square feet. There’s no need for more. Two high-voltage lamps are plugged into a round, made-in-China power strip, just in case, to light a striped curtain. Behind the curtain, a bit of wallpaper representing a seaside landscape with palm trees and flower beds can easily be made out—a landscape of Chinese dreams. This decor serves as backdrop for the images to come. In front of this scene, an ordinary wooden stool awaits. Outside, seated on a nylon-strap chair, the studio photographer also awaits potential clients. If, after this ritual waiting, one shows up, the photographer has him sit on the stool in front of the backdrop. He turns on the lamps. He leans over his camera, glues his eye to the shutter and shoots. He winds up the roll of film, sets an appointment for the customer to pick up the photo and begins awaiting the next likely client.

Confined inside the territory of their studios, a few of these “sentry-duty” photographers have imagined tricks and perfected strategies to attract a clientele. They have acquired accessories (radios, briefcases, Vespas, bouquets of plastic flowers), built sets (multipart frescoes, painted backgrounds, various wall hangings) and prepared costumes (bowler hats, close-fitting jackets, multicolored ties)—all bought at top prices—so that the person being photographed can become more beautiful than he might be otherwise for the duration of the shoot.

With each passing shot, these silent magicians, servants to a narcissistic luxury, have become artists. They are true directors, awaiting the arrival of a subject they can magnify inside a “perfectly decked out,” space. The African photo studio is an artistic space par excellence. There, intimacy can be invented and freedom is always present.

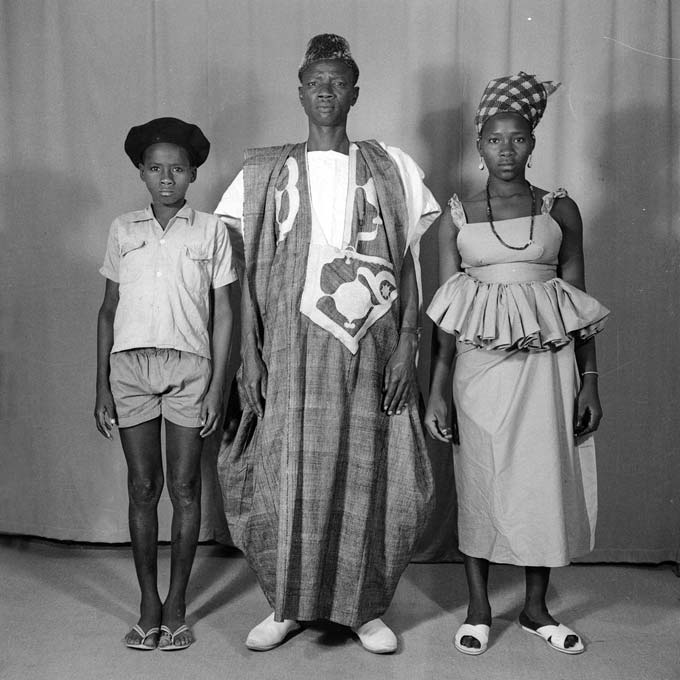

Adama Kouyaté, La famille, 1954.

Photographic production in Mali began with the first European explorer missions and continued with photo studios established in Bamako, the capital, and run by European or Lebanese traders. African photographers entered the picture only toward the end of the 1930s. Printing apprentices, errand boys or housekeeping attendants at first, almost all of them learned the trade through their contact with the master photographer, a white man, who employed them. Then the magic reeled them in. And with varying degrees of success, they opened the first people’s photographic studios and began producing images of their fellow citizens.

Early in the 1960s, there were few photographers in Bamako—six at most. You would find them in the city’s poorer central neighborhoods (Madina Kura, Bamako Kura, Bagadadji, Dravela). Lively and warm, these districts of the capital were inhabited by carefree young people happy to be living in a society that had been launched on a path of high hopes. Every Malian believed that independence would bring about even more reasons to hope.

Adama Kouyaté, Le couple à moto, 1971.

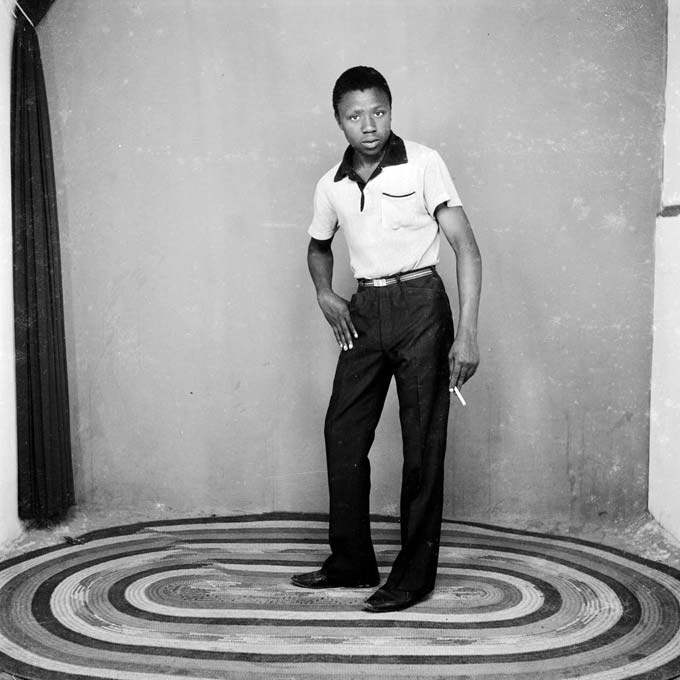

Euphoria was permitted and prevalent. People celebrated and danced with joy at every occasion. Adults were working to build a society that promised prosperity; young people were bound by rigorous social and civic codes, yet at the same time encouraged to experience their age group’s pleasures. In clubs with unambiguous names like “The Friends,” “The Carefree,” “Beach Boys” and “Charming Ladies,” they dressed in the “Yé-yé” fashions shown in European celebrity magazines: bell-bottom pants, tight-fitting shirts and shoes of the darkest brown. They danced to American pop music. They swung to James Brown and Aretha Franklin.

The photographer was witness to and guardian of the happiness of a Bamakoan society that yearned for its image—the image of its new independence.

Adama Kouyaté, Joe Brin, 1967.

In the 1990s, a decade of renewed euphoria for Mali after 23 years of despotism, the West discovered and celebrated two men it considered—and still considers—the greatest photographers of the “dark continent”: Seydou Keïta and Malick Sidibé. The works of these two nearly retired Malian photographers became all the rage in galleries and museums in New York, Madrid, Barcelona, Paris and London.

Anonymous portrait galleries, joyful memories of a famous family, glowing faces from a day’s happiness—a thousand and one images resurfaced and began to circulate in the Western art market, which succumbed to their charms. Mali’s recent and tangible past was now being summoned before the spectators of Africa’s democratic renewal—as if the memory of the hopes that had been reclaimed from oblivion were coming to reassure the new hopes.

Thanks to the West’s infatuation with photographs produced in Africa in the mid-1950s, numerous African studio archives were unearthed, either by researchers driven by an anthropological approach or by curators of all stripes promoting a previously unknown African photography aesthetic. It was at this time that the name Adama Kouyaté finally surfaced, north of the Mediterranean and across the Atlantic.

Adama Kouyaté, Les minieuses, 1971.

Kouyaté was born in Bougouni and remained in this small southern Malian town until age 17. After his cobbler father died in 1944, Kouyaté found himself at the family’s helm. Without resources to provide for everyone’s needs, he decided to leave for Bamako, the capital, hoping to find work there. He began an internship with a master cobbler while waiting to find a better position.

On December 25, 1946, Kouyaté gave his girlfriend a Christmas present: he invited the photographer Bakary Doumbia to her house so that he could take their portrait. “The photo was so beautiful that I wanted to be a photographer myself,” Kouyaté says. “And I never let go of Bakary Doumbia again.” At the time, Doumbia and his brother Naby were two well-known and acclaimed Bamako photographers. Bakary ran the studio in the Dravela district and Naby was employed as a photographer with the National Police Force.

Kouyaté began an apprenticeship at Bakary Doumbia’s side. Very quickly, he familiarized himself with photography and its magic, also becoming acquainted with other photographers’ apprentices and the city’s studios. Finally, he met Pierre Garnier, the master teacher of all the city’s photographers, while admiring the images Garnier had taken and was exhibiting in the window of his “Photo Hall Soudanais.”

Adama Kouyaté, Les deux amies, 1971.

As a result of spending time at the Photo Hall Soudanais, Kouyaté was eventually hired by Garnier as his photo-enlarging assistant in 1947. Two years later, Kouyaté opened a studio in Kati, some nine miles from Bamako, and christened it “Photo Hall Kati.” Becoming a truck driver a few years later, he entrusted the studio to a young man he had trained, who managed the studio while Kouyaté was away. Over a period of ten years, Kouyate traveled all the roads in West Africa, staying in Lomé, Togo; Abidjan and Bouaké, Ivory Coast; and Ouagadougou, Burkina Faso. In Bouaké, a small trading town, he opened another studio, “Photo Hall Ivoire,” operating it until 1968, the year of the military coup in Mali. This event put an end to Kouyaté’s African adventure.

Back in Mali, investigating business opportunities and gathering information about the practice of photography, Kouyaté soon learned that Ségou’s Agence Nationale d’Animation (ANIM, or National Animation Agency)—which served as a photo studio, among other things—was about to close. No studio in town existed to replace it. Kouyaté knew the town of Ségou: in fact, he already owned a house there. An important city in the country, a trading crossroads counting several kings in its history, Ségou had a say in all of Mali’s national affairs. The great Bambara and Somono families kept a vigilant eye on local prosperity. Convinced of Ségou’s commercial opportunities, Kouyaté sold his car and, with the proceeds from the sale, set up a studio specializing in portraits called “Photo Hall d’Union,” in the Adama Seck building on Elhadj Oumar Tall Street, in the heart of the commercial district. The studio was inaugurated on September 22, 1969.

Adama Kouyaté, Mère fille, 1969.

For a long while, Adama Kouyaté remained the only photographer in town. On ordinary days, he was content with taking two rolls of 24 exposures each. In times of celebration—Tabaski (Eid al-Adha), Christmas, Ramadan, baptisms, weddings—he shot as many as six rolls per day. Other photographers eventually settled in Ségou, but Kouyaté never suffered from the competition. Women and young people, the majority of his clientele, always came to him to have their pictures taken.

Today, at the age of 82, Kouyaté continues to take picture IDs in his studio on Elhaj Omar Tall Street in Ségou.

Translated by Christine Schwartz-Hartley. With thanks to Art Dubai 2013, which hosted Amadou Chab Touré’s gallery Maison Carpe Diem in its Marker section.

Adama Kouyaté, Transistor, 1967.

This piece, commissioned by Creative Time Reports, has also been published by Aperture and Whitewall.