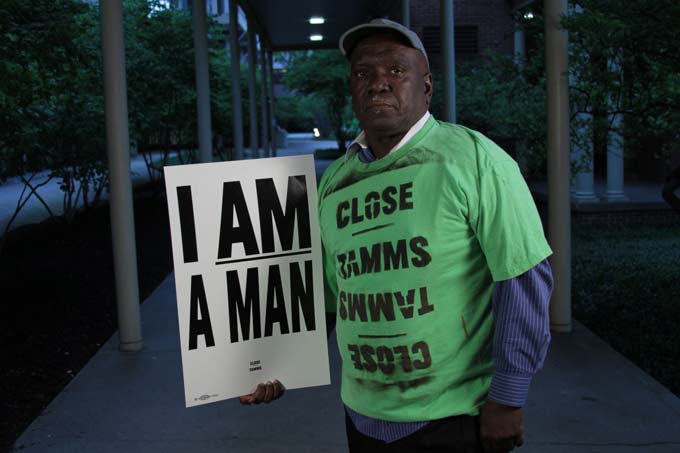

Melvin Haywood, pictured above, spent eight years in solitary confinement at Tamms supermax until the Prisoner Review Board granted him parole from prison. Though the Department of Corrections held him in isolation for eight years, as a “C#,”one of the 270 Illinois prisoners floating in the system with indeterminate sentences, the notoriously tough parole board determined that he did not need to be in prison at all. He credits Goodwill and the Safer Foundation for helping him transition back to society after 30 years of incarceration. Since his release, Haywood has worked to prevent violence by educating and mentoring youth: “To stop the violence, it’s got to come from people from the streets, from the inside—not the academics.” Photo by Lora Lode/Tamms Year Ten, 2012.

Illinois Lost Its Head

In 1998, Illinois opened a prison without a yard, cafeteria, classrooms or chapel. Tamms Supermax was designed for just one purpose: sensory deprivation. No phone calls, communal activities or contact visits were allowed. Men could only leave their cells to shower or exercise alone in a concrete pen. Food was pushed through a slot in the door. The consequences of isolation were predictable: many men fell into severe depression, experienced hallucinations, compulsively cut their bodies or attempted suicide.

Tamms Supermax was designed for just one purpose: sensory deprivation.

The first men at Tamms were transferred there from other prisons around the state for a one-year shock treatment intended to break down disruptive prisoners and make them more compliant. But the Illinois Department of Corrections (IDOC) left them there indefinitely. A decade later, more than a third of the men at Tamms had been there since it opened, and for no apparent reason.

Research has shown that supermax prisons don’t reduce prison violence or rehabilitate prisoners. On the contrary, isolation induces or exacerbates mental illness, creates stress and tension, worsens behavior and undermines the ability of people to function once they get out.

Mothers of men in isolation at Tamms supermax protest the guards union AFSCME for supporting a prison condemned by international human rights monitors. Their signs are based on the “I AM A MAN” placards first used by striking AFSCME sanitation workers, whom Martin Luther King, Jr. supported just before he was assassinated in Memphis in 1968. The mothers said that closing Tamms is about human dignity, not jobs, and reiterated King’s message that workers’ rights and human rights are inseparable. They marched to AFSCME headquarters on April 4, 2012, the 44th anniversary of King’s death, and told the crowd, “Human suffering cannot be the basis of the southern Illinois economy.” Geneva, Rose and Brenda’s sons spent nine, eight and 14 years respectively in isolation at Tamms. Photo by Adrianne Dues, April 4, 2012.

Despite its uselessness as a form of correction, Tamms had many strong supporters: the powerful union to which the prison guards belonged, the nearby towns that welcomed the well-paid jobs, and state officials who thrived on tough-on-crime politics. They all deployed a single phrase meant to paralyze any possible dissenters: the worst of the worst. This slogan was applied to the men at Tamms to suggest they deserved the worst possible treatment—long-term solitary confinement that human rights monitors uniformly describe as cruel, inhuman and degrading, if not outright torture. Challenging this label and this punishment became the project of Tamms Year Ten, a campaign launched in 2008, a decade after the supermax opened.

Punching Above Our Weight

Two years earlier, a group of Chicago artists, poets and musicians formed the Tamms Poetry Committee. Two of them, Laurie Jo Reynolds included, had been members of a group that had protested plans to construct the supermax. Following the practice of two women who sent holiday cards to the prison, we sent letters and poems to every man at Tamms to provide them with some social contact. Their replies demonstrated the necessity of this project: “Hi Committee, is this for real? I can’t believe someone cares enough to send a pick-me-up to the worst-of-the-worst. Well, if nobody else has said it, I will: THANK YOU.” But we quickly found ourselves deluged with pleas for help: “Hey, this poetry is great, but could you please tell the governor what they’re doing to us down here?”

“Photo Requests from Solitary” was one of many projects launched by Tamms Year Ten to build publicity for the campaign. The men in Tamms were invited to request a photograph of anything in the world, real or imagined. The resulting requests were touching and often surprising. They included: the sacred mosque in Mecca, comic book heroes locked in epic battle, Egyptian artifacts, Tamms Year Ten volunteers and a brown and white horse rearing in weather cold enough to see his breath. Willie Sterling III asked for a photograph of a vigil at Bald Knob Cross on top of a hill in southern Illinois to pray for his deliverance from Tamms and to be granted parole. Tamms Year Ten caravanned down to the cross, held a litany of song and prayer and celebrated with a dinner. The next day, we drove family members to visit loved ones at the prison. Sterling was transferred from Tamms, and on July 27, 2012, he was paroled after 36 years in prison. Photo by Rachel Herman, May 6, 2011. See more “Photo Requests from Solitary” on The Daily Beast.

Photographers from across the country offered to fill photo requests for men in isolation. Chicago animator Lisa Barcy, Dutch photographer Harry Bos and Baltimore filmmaker Stephanie Barber each orchestrated a version of one prisoner’s detailed request for a lovesick clown: “A lovesick clown: holding a old fashioned feathered pen: as if writing a letter: from the waist up: in black and white. As close up as possible: as much detail as possible: & the face about 4 inches big.” From left to right: photos by Lisa Barcy, Harry Bos and Stephanie Barber, 2012.

Prison reform is hard enough, but getting people to stand up for “the worst of the worst” was considered hopeless.

By 2008, we had connected with men on the outside who had spent years in Tamms and family members of current prisoners. Together, we launched the Tamms Year Ten campaign. Our goal was to educate the public about Tamms and hold the IDOC, legislators and then-Governor Blagojevich accountable for the use of long-term isolation. Prison reform is hard enough, but getting people to stand up for “the worst of the worst” was considered hopeless. Attorneys and veteran prisoner advocates warned that this campaign could endanger the men and increase support for the prison. But we believed that recent controversy over solitary confinement and torture at Guantanamo Bay and Abu Ghraib opened a new space for debate. And in any case, after a decade of isolation with no end in sight, the men in Tamms didn’t have much to lose.

Outrage Properly Directed

It was hard to know where to begin. Not many people had even heard of Tamms, located at the southern tip of Illinois, 360 miles from Chicago. Our members consulted with legislators from all over the state and sought advice from every quarter. A turning point was meeting Julie Hamos, an Evanston legislator known as a problem-solver. Her moral outrage was gratifying: “Ten years? This is unacceptable.” She felt that the best strategy was to force the IDOC to publicly justify itself. But that meant we had to have enough information to stand up to intransigent prison officials and law-and-order politicians. So we read, researched, filed Freedom of Information Act requests, extracted data from the public record and gathered statements from prisoners and their family members.

State Representatives speak at a press conference introducing HB6651, a bill to reform Tamms supermax prison and the first legislation in the country curtailing the use of solitary confinement. Shown from left to right: Former Tamms prisoner Reginald “Akkeem” Berry, Sr., Representatives Julie Hamos, Karen Yarbrough, Eddie Washington and Connie Howard, and Tamms Year Ten members Stephen F. Eisenman and Jean Snyder. Snyder litigated on behalf of men in Tamms with serious mental illness while she was with the Roderick MacArthur Justice Center. Photo by Laurie Jo Reynolds, May 25, 2008.

On April 28, 2008, our friend, the late Representative Eddie Washington from Waukegan, chaired public hearings on Tamms to focus legislators’ attention on the issue. We were supported by attorneys who had litigated on behalf of men at Tamms with mental illness. The testimony was often wrenching, but the IDOC was unmoved. Nevertheless, the sheer size of the audience—more than a hundred people came out—catapulted our legislative campaign. Through forums, lobby days, press conferences, rallies, prayer vigils and parsley-eating contests, we gained the support of 70 organizations and 27 legislators for a reform bill sponsored by Hamos. She also initiated roundtable discussions between Tamms Year Ten, the IDOC and legislators. The highlight of these meetings was seeing the real experts—the men recently released from Tamms—confront their former captors.

When Opportunities Are Seized, They Multiply

In 2009, the stars began to align. Amnesty International issued a statement condemning the conditions at Tamms as “harsh,” “unnecessarily punitive” and “incompatible with the USA’s obligations to provide humane treatment for all prisoners.” The organization contacted Illinois state officials, urging them to support our reform legislation. So did Human Rights Watch. Then Representative Luis Arroyo encouraged us to present our case to the House Appropriations Committee during its annual review of the IDOC budget. He opened the session with remarks about how international human rights monitors—and his own constituents—wanted the torture at Tamms to end. The hearing became a referendum on the supermax.

A month later, and just a year after the campaign went public, our new governor, Pat Quinn, announced he was replacing the IDOC chief with a reform-minded director whose first task was to review the supermax. This was followed by a Belleville News Democrat exposé that described men at Tamms with untreated schizophrenia and knots of scar tissue from self-mutilation. It also documented cases in which men entered Tamms with short sentences but wound up with life terms because of their mental illnesses. Their investigation revealed that more than half the men at Tamms had never even committed an offense in another prison. Amnesty released another, more strongly worded statement asserting that “the conditions at the supermax flout international standards for humane treatment.” In September 2009, the IDOC director announced a 10-point plan for reform that included an improvement in conditions, meaningful due process hearings and an administrative review of each man in Tamms. We had cracked the nut.

Torture Is a Crime, Not a Career

By 2011, the promised reforms were stalled, in spite of a new federal court ruling that men at Tamms had been deprived of their due process rights. But at just this point, Representative Arroyo became Chair of the House Appropriations Committee, and pushed not for the reform, but for the closure of Tamms. And in February 2012, Governor Quinn followed suit due to the state’s budget crisis and human rights concerns. In response, downstate legislators and the guards’ union (AFSCME) orchestrated a scare campaign, falsely asserting that closing Tamms would make the prison system more dangerous. Family members, outraged by the union’s shamelessness, responded: “Torture is a crime, it shouldn’t be a career.” The battle played out in the media, the courtroom and especially the budgeting process. Last year was considered “one of the most contentious episodes in the history of Illinois penitentiaries” and the mothers, sisters, nieces, children and spouses of Tamms prisoners were at the forefront of the struggle to shut the supermax down. They lobbied legislators weekly in Springfield and led marches and rallies in Chicago.

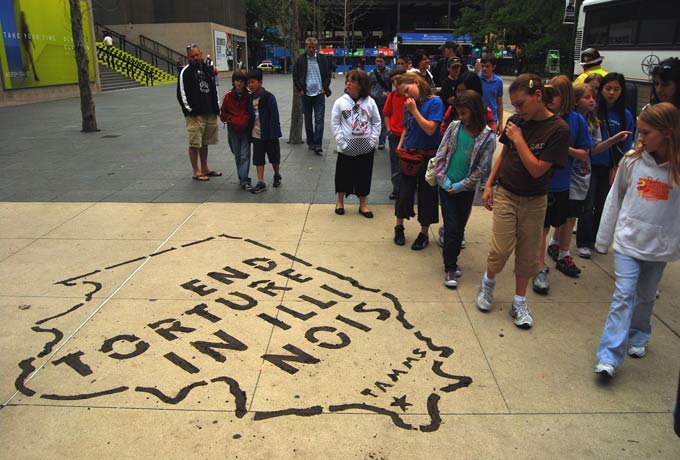

Children look on at a mud stencil outside the Museum of Contemporary Art, Chicago, part of a tactical media project led by Nicholas Lampert and Jesse Graves to publicize the torture at Tamms. Teams of activists traveled the city with buckets of mud and imprinted walls and sidewalks with this unique form of ecological messaging. Photo by Sam Barnett, April 11, 2009. Design: Mathias Regan.

As political artists with real-world political goals, we needed to engage with government systems.

Illinois has no private prisons and a Democratic supermajority in both chambers, yet it is notoriously difficult to close any state facility. We don’t have 50,000 people in prison because of an amorphous “prison industrial complex” hell-bent on selling uniforms, steel doors and honey buns. This state’s mass incarceration can be explained by a powerful guards union, Democratic legislators beholden to it, downstate legislators zealous to protect jobs in their districts, and mass media that promote fear-based policies. It takes guts to close a prison anywhere, but it is especially hard in Illinois. Yet Governor Quinn exemplified true leadership and closed Tamms on January 4, 2013. He chose fiscal prudence over pork-barrel spending; evidence-based policies over myth and fear; and human rights over vengeance.

Why Artists?

Artists were fundamental to the campaign to close Tamms. Accustomed to attempting the impossible, artists are well qualified to affect law and policy. And compared to the typical political players, they have the freedom of the outsider: they are in the world, but not of it.

For centuries, artists have been concerned with systems of ratio, perspective, symmetry, geometry, anatomy, tactility and optics. For the last 50 years, they have taken on ecology, real estate, advertising, media, cybernetic, genetic, language, gender, racial and class systems. As political artists with real-world political goals, we need to engage with government systems. That’s legislative art. Prison policies are made by the state, so you go to the state to change them.

In 2012, the School of the Art Institute of Chicago exhibition “Tamms Year Ten Campaign Office,” in the Sullivan Galleries, served as the hub for the campaign to close the supermax. The office contained all the files and ephemera from the then five-year-long political battle and was the site of an active campaign. Volunteers met and worked around the clock while gallery visitors stopped by to observe, ask questions and even sit down and help. Photo by Tony Favarula, 2012.

It is therefore fitting that the Tamms Year Ten office—filled with five years of files, fact sheets and ephemera—became an art exhibition in the Sullivan Galleries at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago last year. It served as the hub of the Tamms closure campaign, on view and in action, without any division between art and politics.

This campaign required the endurance, commitment and even obsession characteristic of an artistic practice, as well as the faith and unity of hundreds of people working together. Tamms prisoners sent critical information, galvanizing testimony and prayers. Men once active in rival gangs publicly spoke side by side about the damage of isolation. Even families of men no longer in the supermax lobbied for sons left behind. Artists lent their skills, advocates issued statements, attorneys battled in court—and principled public officials stood their ground. Those who had stumbled alone for years forged a collective path. Out of isolation came solidarity.

We are enthusiastic about legislative art because it is engaging, unpredictable and rewarding. But mainly because it is necessary.

—

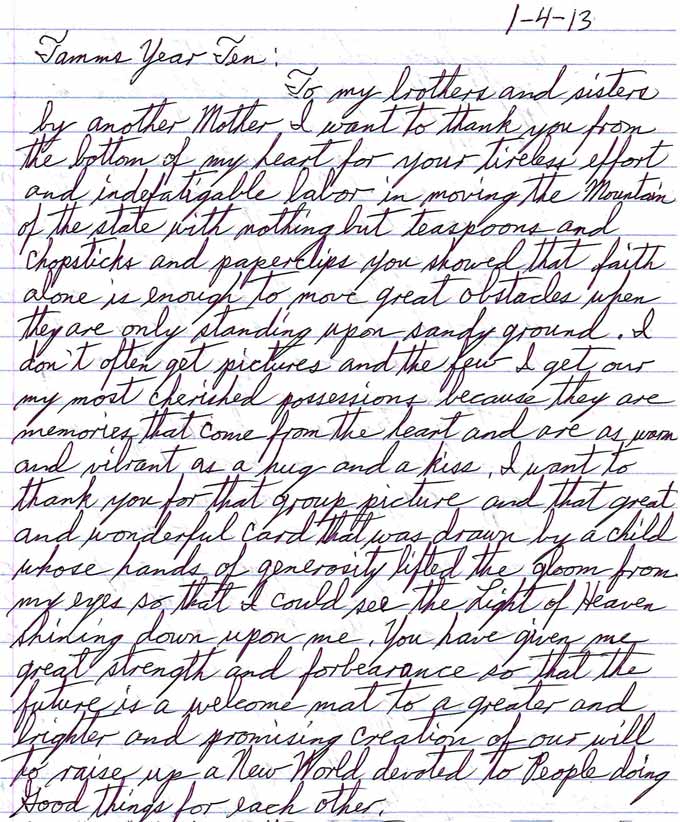

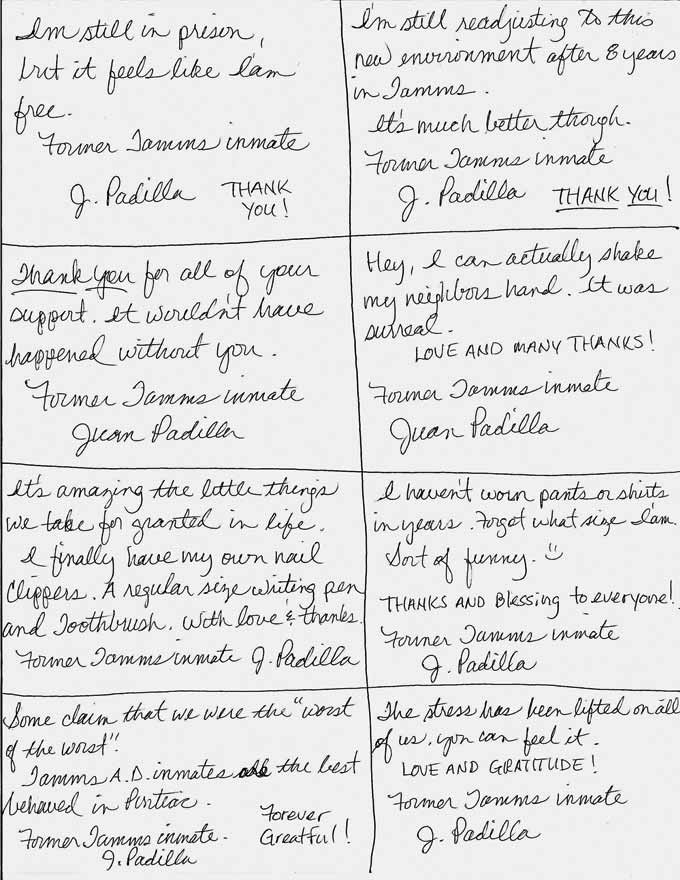

Below are a selection from among dozens of letters written by men after they were transferred out of Tamms, thanking Tamms Year Ten volunteers for their help in closing the supermax.

“To my brothers and sisters by another Mother, I want to thank you from the bottom of my heart for your tireless efforts and indefatigable labor in moving the Mountain of the state with nothing but teaspoons and chopsticks and paper clips. You showed that faith alone is enough to move great obstacles when they are only standing upon sandy ground.”

The Tamms prisoner who wrote this letter started to hear voices and cut himself while in solitary, and was subsequently diagnosed with several mental illnesses. In the same letter, he wrote that “all the medication in the world won’t make me forget what I suffered at Tamms.”

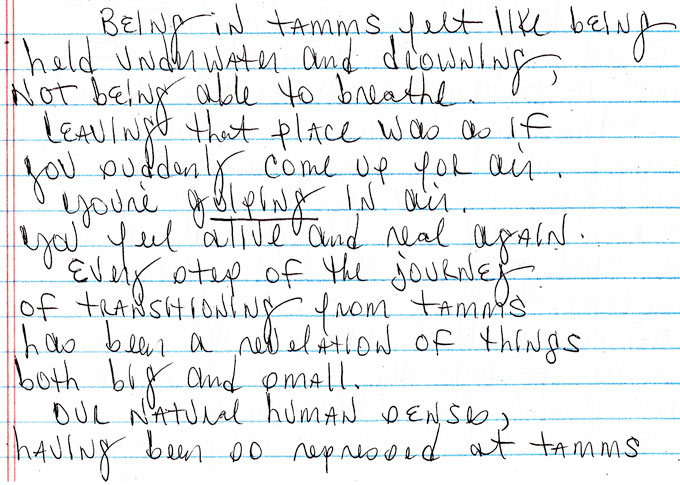

“Being in Tamms felt like being held underwater and drowning, not being able to breathe. Leaving that place was as if you suddenly came up for air. You’re gulping in air. You feel alive and real again. Every step of the journey of transitioning from Tamms has been a revelation of things both big and small. Our natural human senses, having been so repressed at Tamms, were suddenly and shockingly activated simply by boarding the I.D.O.C. bus. The smell of diesel fumes was overpowering, its presence a turbulent mixture of ambivalent sensations; foreign yet familiar, comforting and nauseating, pleasurable yet unsettling. Shuffling into the bus was a formidable task: the waist and leg shackles severely hindered our movement and were as uncomfortable as they were difficult, yet every prisoner from the first to the last man had the biggest smiles on their faces.”

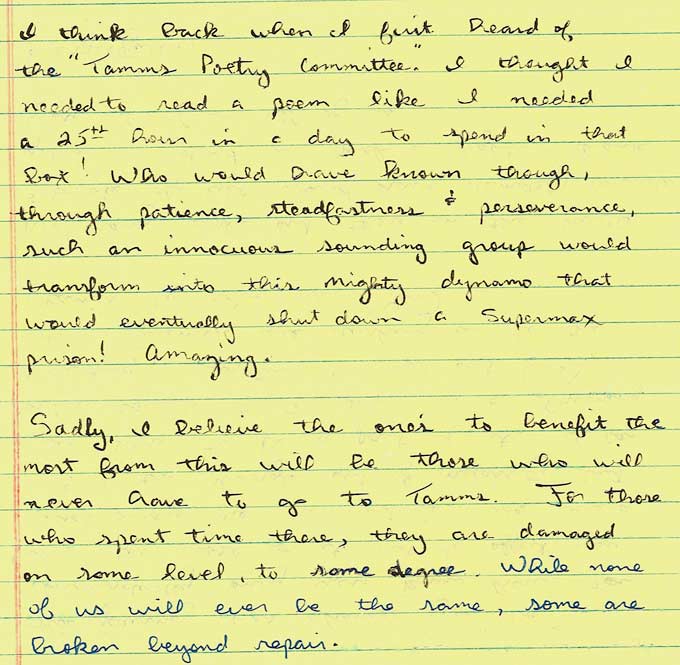

“I think back when I first heard of the ‘Tamms Poetry Committee.’ I thought I needed to read a poem like I needed a 25th hour a day to spend in that box! Who would have known though, through patience, steadfastness + perseverance, such an innocuous sounding group would transform into this mighty dynamo that would eventually shut down a Supermax prison! Amazing.

“Sadly, I believe the ones to benefit the most from this will be those who will never have to go to Tamms. For those who spent time there, they are damaged on some level, to some degree. While none of us will ever be the same, some are broken beyond repair.”

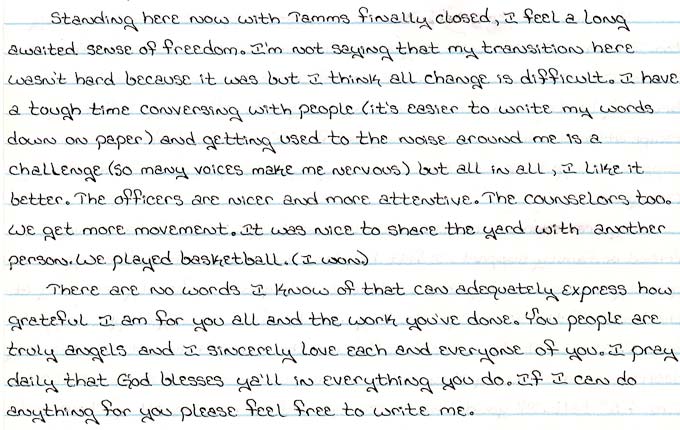

A former Tamms prisoner shares his elation at experiencing relative freedom in small ways. Elsewhere in the same letter, he writes:

“Hey, we can finally go outside with more than one person. Still takes time to get use to it. THANK YOU! …

“The support we received from everyone is inspiring and emotional. YOU WILL NEVER KNOW HOW MUCH YOU ALL TOUCHED US! THANK YOU ALL! …

“I can finally wear some sweat pants. No more jumpsuits. I even have my own bowl. It may sound trivial, but I haven’t had one in over eight years. A MILLION THANK YOUS!”

This drawing was made by a boy whose father was held in Tamms, as he anticipated the closure of the supermax. Once it closed, Tamms Year Ten sent a copy of the drawing as a New Years Day card, signed by volunteers, to each man transferred from Tamms to other prisons. The positive feedback has been tremendous.

—

“Tamms Is Torture” is part of an ongoing Creative Time Reports series on U.S. prison reform, which also includes dispatches on solitary confinement from filmmaker Angad Bhalla and photographer Christoph Gielen. This piece, commissioned by Creative Time Reports, has also been published by Alternet and TruthOut. You can view more of the “Photo Requests from Solitary” featured above via The Daily Beast.