Ngwatilo Mawiyoo, Moyale’s wholly segregated residential neighborhood, 2013.

Getting to Moyale from Nairobi takes two nights and a day by lorry, nonstop, with one driver intermittently chewing khat along the way. That’s how I go. There is a bus, but I am advised that the lorry will be more comfortable, especially once the tarmac ends. The badness of the road is legend, so everyone who can flies to Moyale instead.

Leaving Nairobi by highway, you learn that Moyale is 488 miles away—north. North into the place the colonialists named the Northern Frontier District. Beyond where the rest of us in the south believe good news can be borne. North into that bush where they ask you for news of Kenya. Past Isiolo and the shiftas (“bandits”) on the loose beyond it. Past the deserts and the oasis at Marsabit. Almost Ethiopia: Moyale.

In the lorry I sit beside a Borana man. I can’t tell that he is Borana, he tells me. I’m wearing a hijab, newly acquired from the Somali and Woria outpost in Nairobi—Eastleigh—because I imagine it will help me blend in, and it does. The old man thinks I look Borana. “Blood calls to blood,” he says in Kiswahili. And my blood calls to him. He blesses me. He says he prays that I will find a rich husband. He tries to speak Borana to me, even though I tell him I do not understand it. He says he does it to test me. I only hear syllables hurriedly beating past my ears, and fading off quickly as if they’d died when they came too close.

Ngwatilo Mawiyoo, Log Logo, looking south, 2013.

Somewhere between Isiolo and Marsabit, in the heat of the day we stop in an outpost called Log Logo. It has no electricity, no phone signal. There are many small shops on either side of the road. The sign over one, announcing “COLD DRINKS AVAILABLE,” sells a fiction. Two vehicles pass by: one from an NGO, the second, a government vehicle. An oil tanker sits parked, likely also on the way elsewhere. The land is flat. I see only dust and occasional bush.

The old man beside me gazes at the Rendille warriors leaning against their staffs beside our truck. “They are not even animals,” he says. To me, the warriors look ready for their photographs to be taken by National Geographic. Their skin gleams in the sunshine, hair perfectly braided and ocher red, protected from the dust by hairnets. Around their waists they have wrapped bedsheets that sit like skirts, leaving their torsos naked, except for two strings of beads draped across each shoulder like sashes, crossing at the sternum. I’m not sure what exactly offends the old man about them other than the hairnets they wear “like women.”

Everyone has a gun, whatever they tell you, whatever they tell the government. In this area, you need one.

Blood and blood and dust will mix after Election Day on March 4 if the Gabbra win the Marsabit County governor’s seat. We’ve reached Moyale. It’s my third day in the border town. I’m speaking with one of Moyale’s white-collar Somali Garre professionals. He’s insistent that our conversation must not be taped, and that he remain anonymous while talking about the politics of Moyale, lest his people consider his words a betrayal and come after him. People are ready for war, he says. He is ready. He owns a gun, which cost him about $465. They are sold at the market like potatoes in Ethiopia, he says. Everyone has one, whatever they tell you, whatever they tell the government. In this area, you need one.

My host family is Gabbra. The father, Ali, is well into his forties or fifties, and looks after his aging mother, his two wives and their six children, one of whom is away in the south of Kenya—what they call “Down Kenya” here—in high school. Safe. Ali’s mother has her own house, a single room that shares a wall with Ali’s first wife’s bedroom and living room. The second wife lives in a separate building in the homestead, which contains her bedroom and living room. There is one kitchen and one pit latrine and bathroom outside. Beside their homestead they also have a patch of land where they recently harvested what they called a relatively poor crop of maize and beans. Beyond the whole property up on a neighboring hill, is their local mosque, where the men go for daily prayers. The women pray inside their homes.

It takes me a while to know which child belongs to which woman. I sleep alone in the living room of the first wife and cannot tell how I’ve disrupted the family’s sleeping arrangements. The three young children—a girl, a boy and a second girl, about nine, seven and five years old, respectively—sleep in the second wife’s home. One evening, the first wife returns from town with new underwear for the boy, and a new schoolbag for the five-year-old, who started nursery school that week. Elated, the boy tries on the two pairs of underwear right there in the living room. “Alhamdulillah!” he says over and over again. He was wearing no underwear beneath his jeans, so he leaves a pair on. The older boys sleep at the boarding school nearby. One is a student in his final year of high school; the second is in his gap year, waiting for exam results, having finished high school last December.

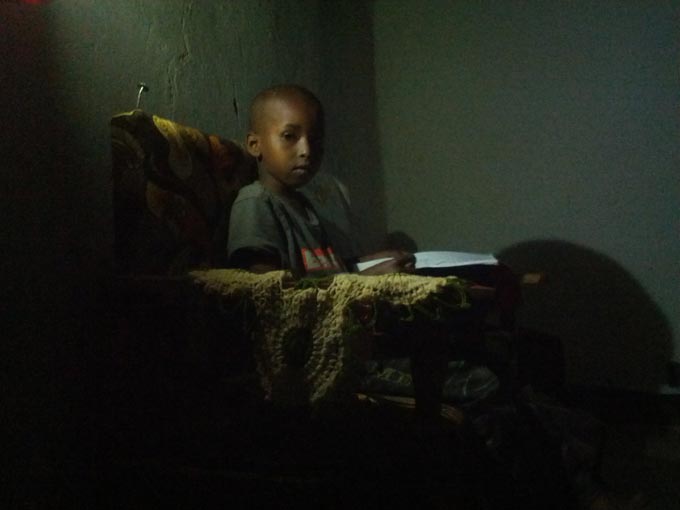

Ngwatilo Mawiyoo, My host brother looks up from practicing his numbers in the solar lamplight, 2013.

In the end I decide all five children I see belong to the second wife, and that the girl away in boarding school belongs to the first wife. But the father’s affections seem shared equally between both wives: one night he sleeps with one wife and the following night with the other. At suppertime, everyone speaks easily and participates in the discussion, including the women and children. The women always seem to eat last, although they do not appear oppressed by the habit. The youngest girl is most playful; her father lets her climb on his back and sit close beside him and tell him stories.

This is the volatile north, the region where people who speak the same language, who cannot tell each other apart on sight, are accustomed to making war with each other. We in “Down Kenya” understand even less of the nature of the trouble, because we tell ourselves that our mistrust for other southern ethnicities is based on more absolute differences, like language and culture; that we, unlike the people of the north, are getting over our differences with our neighbors and moving on. But whenever conflict occurs in the north or south, its root is pretty much always political.

There are four ethnic groups living in Moyale town and the larger Marsabit County: the Rendille, the Burji, the Borana and the Gabbra. There are also some Garre people in Moyale, one of the Somali clans. I read that the Borana and Gabbra both originate from the ancient Oromo people of Ethiopia.

In July 2005, 90 Marsabit County residents—including 22 children in primary school—were murdered just southwest of Moyale.

When the people I meet try to explain the cause of the historic conflict between the Borana and the Gabbra, they tell me that these lands, from Isiolo near the center of Kenya northward beyond the border, were originally Borana lands. They say the tension emanates from the settlement of other groups, especially the Gabbra in the Moyale area and the Rendille farther south, given the limited pasture and water resources for their animals.

In July 2005, 90 Marsabit County residents—including 22 children in primary school—were murdered just southwest of Moyale, in what became known as the Turbi massacre (PDF). The Borana fear that the Gabbra will use the governorship to take revenge for the killings, which targeted them. The following April, four parliamentarians who represented the Rendille, Gabbra and Borana died in an airplane crash as they attempted to land in Marsabit, ahead of a meeting they had arranged to call for peace among the county’s ethnic groups. Their death threw the peace effort into disarray. But a local community worker I met, who also preferred to remain anonymous, believed the deceased parliamentarians were responsible for arming their communities ahead of the massacre. At The Truth, Justice and Reconciliation Commission hearing in Marsabit six years later, the local police division likewise testified that the politicians had incited locals against one another in the period leading up to the massacre.

Ngwatilo Mawiyoo, Off to a political rally, 2013.

Tensions rose again in Moyale starting in October 2011, reaching a crescendo in January 2012. The Kenya Red Cross Society reported that at least 60 people on both sides were killed and another 57 seriously injured, and that over 1,000 homes were burned down and 5,000 families displaced. The report cited “competition over positions in the County Government structures as designated in the New Kenyan Constitution and land-related issues, following a review of boundaries by the IEBC (Independent Electoral and Boundaries Commission)” as the alleged cause of the conflict.

I am ready, in case the time to run comes early.

At night my host family shares the evening meal on a mat outside, under the stars, often eating from one tray or in pairs sharing a plate. The older daughter daughter in my family, Aliya, a mere child in grade six, tells me how she and her family ran in January, 2012 under the gunfire, out of their neighborhood through the Garre homes, out and across the border into Ethiopia, directly to the home of the relatives they have there. They left with nothing but the clothes on their back. She tells how they were met with tea and water and bread when they arrived, and the joy of the other children who had found new playmates. How her grandmother trudged in some time after they had rested, together with one of her mothers, her grandmother near death with exhaustion. And how her older brothers were left to deliver supplies to the fighting warriors. Ibrahim, the eldest, thinks there must have been more people who had died—300, he estimates—lying on the narrow paths between the homes in the heat of January. Hyenas would eat them at night, he says.

That night and for the rest of my nights in Moyale, I sleep under the net on that mattress in the floor of the living room with my passport, my phone, lip balm and wallet so I am ready, in case the time to run comes early.

—

My host family got off lucky. They lost their donkey, their furniture was stolen, and whatever wasn’t stolen was either broken or burned. But they made it out alive, and their houses were not damaged too seriously, although the looters tried to burn them down.

Ngwatilo Mawiyoo, My host family’s back yard, and its broken reminders of the January 2012 Moyale clashes, 2013.

Ali’s herd of camel remained safe out in the bush, looked after by someone in his employ. Ordinarily they would graze close enough to supply the family with milk, ferried by donkey, but during that conflict, and now in the face of potential election-related clashes, he’s sent them farther out, beyond where they could get caught in the crossfire.

When we walk through the neighborhood, we see that others have not fared as well. Some houses still lie damaged and abandoned. Their owners have not returned from Ethiopia, Ibrahim says.

Making war is strangely easy in Moyale. Each community lives in a particular place, so if one means to harm the Gabbra or Borana or Burji or Garre, one will know exactly which neighborhood to hit. It’s not safe for Ibrahim to take me into the Borana neighborhood, but I know they, too, have scenes like this. Before the 2012 clashes, Ibrahim says, they used to invite and receive invitations from their Borana neighbors to family celebrations and functions. The past year has been decidedly different.

Moyale Girls High School is running at half its student capacity. Teachers have also left; because of the insecurity in the area, they have been granted transfers without conditions. Classrooms lie empty. At the school’s high point, over 70 students sat for the national exam. Last year there were about 49. This year only 38 candidates are expected to sit. The low numbers speak to the continued vulnerability of families who send their children to this school; some have not even come back from Ethiopia. Parents with greater means usually send their children to study in Down Kenya, saving them the disruptions of life at home.

—

The Gabbra candidate will win the race for governor because the Gabbra have come together with the Burji, Rendille and Garre to act as a single voting bloc. The Borana know this, and may cause chaos on Election Day to disrupt the voting process. I learn this over dinner with my family. They think if there’s sufficient security on Election Day, disruption might be prevented.

Making war is easy in Moyale. If one means to harm the Gabbra or Borana or Burji or Garre, one will know exactly which neighborhood to hit.

Already, they say that there are local non-state patrols—militia—ready to thwart off any attacks in the neighborhood.

I speak with Mohammed, a local working toward food security for communities in the region. I’m concerned about how in this state of crisis the county will reach the development and self-sufficiency of Kenya’s other counties. Mohammed isn’t hopeful. “We may never catch up with the other [Kenyans] because the community is not focused on trying to reach them . . . People vote for leaders for absurd reasons here: the candidate’s good looks, his public-speaking prowess, his ethnicity.” I know from my travels that the story isn’t too different in other parts of Kenya, but the cost seems worse here. I’m told there are families in the surrounding area who have practically raised their children on relief food.

World Vision did a baseline survey two years ago in the neighboring Gulbo area. It found that 91 percent of its residents were illiterate. Thus it estimates that the general Moyale region cannot score better than 85 percent. By the end of the first week of February 2013, just one month away from elections, there was no civic education happening in Moyale, and very little voter education.

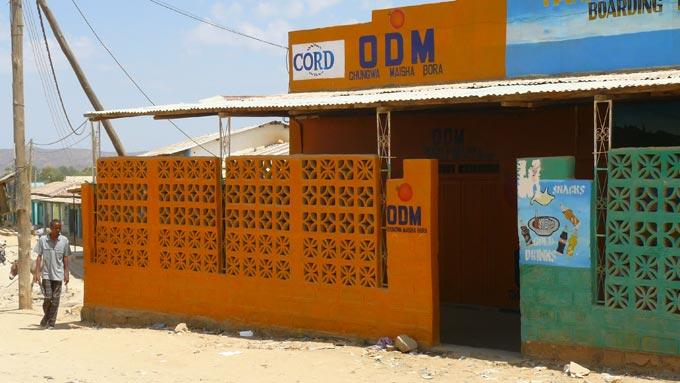

Ngwatilo Mawiyoo, Raila Odinga’s Orange Democratic Movement (ODM) office in Moyale town and the CORD Coalition office, which brings together ODM and other parties, 2013.

Meanwhile, huge amounts of money are being dished out to buy voter attention and influence in Moyale and Marsabit County. During my ten-day visit, Ibrahim makes six dollars one day after attending a youth meeting where one of the political aspirants spoke. He will attend more meetings. He tells me the more influential older men can receive over $1,000 from a single candidate. To date, Martha Karua is the only presidential candidate who has declared that her campaign has and will be free from those handouts. She faced nearly violent protests at one meeting, signaling how connected free money is to our country’s electoral process.

My host families in Nyeri and Kwale counties agree that this strategy was introduced by former President Daniel Arap Moi to hold on to power. Its endurance into Mwai Kibaki’s presidency suggests that despite the progress of the last ten years, parts of our democracy are still broken. President Moi’s legacy of corruption is still alive and well, and both front-runners, Uhuru Kenyatta and Raila Odinga, will take it forward into the “Second Liberation” that our new constitution—ratified in 2010—promises. The cost of these handouts is real, if difficult to perceive when more than 30 percent of the national budget is lost to corruption. Many have come to believe that election time is the common man’s time to eat, after which leadership will continue to synonymize itself with corruption. But we enduringly hope for better.

They’re starting to woo us with more than their personalities and kinship, but some promises sound more like fairy tales than achievable plans.

Lost in the story of Moyale and the March 4 elections are the actual issues that would better the lives of the communities. One suggestion was for a slaughterhouse and meat-processing plant, given how central livestock is to the county’s economy. At the moment people must pay to transport their animals to Athi River just an hour outside Nairobi to access the same services. The deputy head at Moyale Girls lamented that the area MP, now a contestant for the governor’s seat, did not once come into the school during his term, or issue the bursaries his Constituency Development Fund money is supposed to facilitate. Safe water is still far off in the entire county, necessary not just to curb waterborne disease infections, but also toward peace and security in the region. And there are many other issues. But when I spoke to one of the area aspirants, she asserted that it is impossible for leaders to speak about issues even if they wanted to, given the ferocity of the ethnicity-based competition. You have to secure your win first.

Across Kenya the issues candidates wish to address are more audible. Both Kenyatta and Odinga pledge to spend 10 percent of the budget on infrastructure these next five years. Both promise free secondary education, an advance from the free primary education instituted by President Kibaki. Kenyatta’s team goes further to pledge a solar-powered laptop for every primary-school student. Both teams also promise universal health care and investments in agriculture. It’s not clear what will come first, or how they would have us citizens pay for all of this exactly, but it feels like they’re starting to woo us with more than their personalities and kinship, even though some promises sound more like fairy tales than achievable plans.

Kenya’s new constitution takes a decisive step away from the former centralized government system in introducing the 47 counties, each wielding power to direct its own development, assisted by a portion of the national budget and a new freedom to generate additional funds. The new constitution effectively brings power closer to the people, which couldn’t be more useful in the largely ignored backwoods of Marsabit County. One might have hoped that counties would set aside any local politics to set themselves up for new competitiveness and development. But in Marsabit, county politics is the powder keg; the question of whether Odinga or Kenyatta will be president is neither here nor there.

Ngwatilo Mawiyoo, Uhuru Kenyatta’s National Alliance office, alongside the office of his running mate William Ruto’s United Republic Party, 2013.

From Nairobi out to the rest of the country, loud appeals for peace reverberate on TVs and radios everywhere, meeting with whispers of fear and hope in the streets and villages. There are even ad spots with each presidential candidate pledging to accept the results of the election, to concede the presidency if they lose. Hardly a week before the March 4 elections, the candidates publicly embraced during national prayers. Surely, Kenya has armed herself against the seduction of violence. Surely.

But news always reaches Moyale last, if the length of the road trip or the two-day-late newspaper are anything to go by. Only time will tell whether this effort is reaching Marsabit county candidates and their supporters, since it’s always a matter for discussion whether they are in Kenya or not in the first place. But even if we get through the elections in Marsabit County peacefully next week, the new county leadership will need to do some real honest work to create a harmonious, secure and peaceable living and working environment for itself and its residents.

I head home disillusioned about the future beyond these elections. In Nairobi, an entirely different script and host of narrators are inciting peace, speaking it into being, and succeeding, effectively using the same tools leaders used in 2007 to create the opposite effect. I don’t want to rock this boat. So after writing these words, I begin to wonder whether I shouldn’t simply discard them and keep quiet about the trouble brewing in Marsabit, as my contribution toward a peaceful election. But an artist friend tells me if things go well, people will need to understand what we overcame. So be it. Until everyday people create the peace, become it wherever they are, until they can’t be enticed away from it. Until then.