A.L. Steiner, 2003. Photo courtesy of Stop Onestar Press.

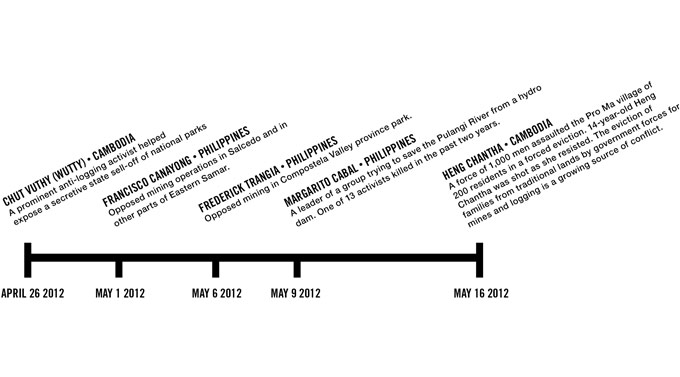

Environmental leaders killed between April and May 2012. Data courtesy of Global Witness.

Approximately one environmental activist was killed per week over the last decade.

We have entered a new phase, a new era, a new epoch—it’s visible, palpable. Population and credit grow exponentially, straining and eroding natural resources. The economic crisis is intrinsic to the ecological one: it’s been calculated that “we are using 50% more resources than the Earth can provide. By 2030, even two planets will not be enough.” Technology cannot keep up with our use of—and impact on—the planet, but those who recognize and fight against this dire fact endanger themselves: approximately one environmental activist was killed per week over the last decade, according to a report from Global Witness. From 2002 to 2011, approximately 711 people were murdered “defending their human rights or the rights of others related to the environment, specifically land and forests.” Among these activists, 106 were killed last year alone—nearly twice the death toll from 2009. The report clarifies why these activists were intent on disrupting the mining, logging, agricultural, hydropower, urban development and wildlife-poaching industries, and why such violence will worsen:

“The pressure on these finite assets has already taken its toll—only 20% of the world’s original forest remains intact and 25% of land has become increasingly degraded in the past 20 years. Yet global demand for land and forest (for food, fuel, fiber and other resources) is predicted to increase—pushing the frontiers of investment further into areas with inadequate governance, tenure rights and rule of law.”

Capital is our political system and money our shared language. Our pleasure is enmeshed in materiality.

The murders of environmental activists are intrinsically linked to resources needed to fuel the U.S. economy: forests, land and sea crops, fuel, water, and precious and raw materials. Extractions, fracking and harvests of these resources result in an endless stream of violence, destruction, disruption and abuse, which only occasionally receive press or celebrity attention. Waste and destruction are the lifelines of these opaque economic structures, and resistance to these exploitative processes is often classified as “eco-terrorism.”

Ecological activists attempt to stop forest destruction in Khimki Forest, near Moscow, and clash with security forces, 2011. Photo by Yuri Timofeyev.

We’re psychologically stuck in a destructive cycle of short-term growth and long-term memory loss.

As things stand now, economic “rights” trump human rights. A radical ecological consciousness is detrimental to the prevalent capitalist framework. Imprisoned environmentalist Tim DeChristopher—who successfully stopped an illegal Bureau of Land Management timber sale in Utah—underscored this tragic impasse when he stated, “Maybe greed and competition weren’t the best values to be basing our civilization off of.” The silencing, harassment, abuse, indictment, imprisonment and murder of environmental activists hinder broad ecological awareness and systemic change. As a country, we fail to recognize or willfully ignore the severe injustices that befall those who advocate for these radical and necessary changes. Mostly because we want our stuff.

Simple math tells us that we can’t continue on this path for long. As our post-industrial economy transitions, falters and attempts to shift toward renewable/reusable/zero-waste systems, we’re psychologically stuck in a destructive cycle of short-term growth and long-term memory loss. The bulk of Earth’s inhabitants are part and parcel of exploitative economic schemes, a majority of us caught in the throes of a machine which keeps us competitive, overwhelmed, under/uncompensated, distracted— unaware of its intentions, effects and illogic. We participate in systems of production and consumption fueled by false notions of scarcity, heteronormativity, white supremacy and success. For those who do not or cannot acquiesce, these profit-based systems will deny housing, water, food, education and healthcare; they will offer violence, poverty, imprisonment or military enlistment as primary alternatives.

We must understand how to “share or die,” begin to know the languages, processes and implications of sustainability.

A nationalized suspension of disbelief distorts and erases so many urgent and intertwined environmental socioeconomic geopolitical issues, encouraging the under-reporting of accurate and critically necessary environmental news and information; the replacement of income with debt; the mass expansion of for-profit prisons, pensions and health care; the rationalization of perpetual global-finance thievery; the demonization of solidarity, social justice and community-based movements; and, the establishment of a privatized police state to protect this system of “organized irresponsibility” known as the GDP. Questioning the accepted terms of this economic framework, feminist economist JK Gibson-Graham, posit:

“How we represent something like an economy influences how we think about what is possible. If we see the economy as naturally and rightfully ‘capitalist’ then any economic activity that is positioned as different (e.g., involves non-market transactions, or non-waged labor, or shares surplus) cannot be viewed as legitimate, dynamic or long-lasting. The ‘capitalocentrism’ of economic discourse subsumes all economically diverse activities as ultimately the same as, the opposite of, a complement to or contained within capitalism. One effect of allowing a representation of the economy as ‘really capitalist’ to stand unchallenged is that something like the social economy is automatically drawn into comparison and devalued, and its innovative potential is considerably undermined…”

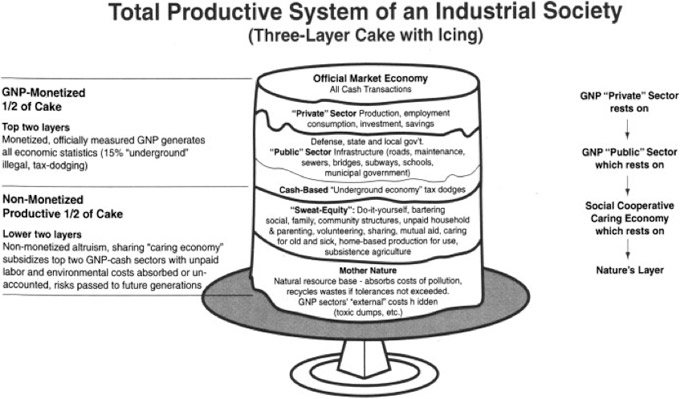

Hazel Henderson’s “Layer Cake With Icing” helps illustrate these formulations of “capitalist realism.”

Hazel Henderson, Total Productive System of an Industrial Society, 2005.

In order to flip this cake, economist Juliet Schor proposes that we rethink “the question of scale, knowledge transmission, the role of informal economies and social capital, new consumer patterns, and the relation among productivity growth, output and hours of work…what was efficient…in an industrial economy is not what is efficient, optimal or profitable in an ecologically-oriented economy.” So, how do we make this leap?

Short-term decisions must be fused with long-term goals, allowing us to participate in the systems-at-large differently. We have to look in order to know what we’re looking at (SEE: Surviving Progress). We need to find ways to understand and solve problems, reprioritize, redistribute, change and learn from activists such as Vendana Shiva, Tan Kai, Caroline Cannon, Julia Hill, Rueben George, Chico Mendes, Ken Saro-Wiwa, Wangari Muta Maathai, Carla Cloer, Yevgenia Chirikova, Judi Bari, Ma Jun, Rachel Carson, Anote Tong, Adelino Ramos, José Cláudio Ribeiro da Silva and Maria do Espírito Santo, Naomi Klein, Annie Leonard, Chief Raoni Metuktire, Edward Mazria, Cesar Chavez/UFW, José Bové, Bill McKibben, Josh Fox, Evo Morales, The Seikatsu Cooperative, Ursula Sladek, Prigi Arisand, and thousands of others who have put their careers, livelihoods and lives on the line. We must understand how to “share or die,” begin to know the languages, processes and implications of sustainability. There are dire consequences resulting from our everyday decisions, cravings, follies, distractions and waste: the sacrifice and death of other humans, species and environments that surround and sustain us. Individually and collectively—at all moments—we must attempt to choose paths other than those of consumption, disposability, insatiability and complicity. Sign up and sign on. We’re in for the fight of our lifetime, and beyond.

This piece, commissioned by Creative Time Reports, has also been published by visualMAG.