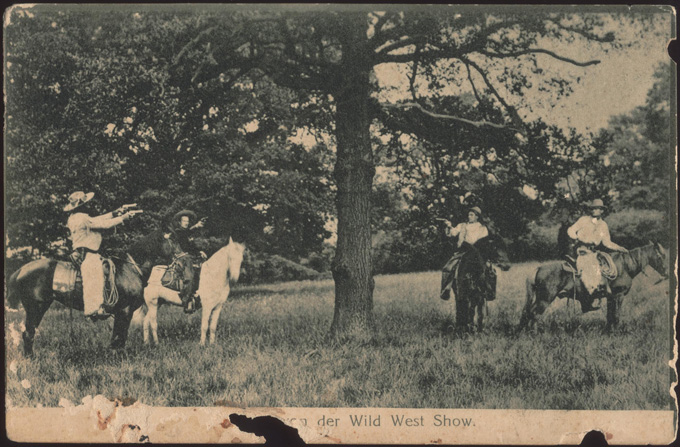

Ken Gonzales-Day, der Wild West Show, Erased Lynching Series, 2004-2016, chromogenic print, 4 x 6.5 inches. Image copyright, Ken Gonzales-Day. Courtesy of the artist and Luis De Jesus Los Angeles.

Black Lives Matters mobilizations in the United States include brown bodies, brown bodies marching, brown bodies protesting and brown bodies bearing witness. This solidarity makes sense, especially as blacks and Latinos in the United States also have a shared past—from the mid-1800s through the 1920s, mobs in the West and Southwest murdered thousands of Mexicans, many of whom were hung from the same trees as African-Americans. And today Latinos often live in the same neighborhoods as black people—like Ramsey Orta, the 24-year-old Puerto Rican man who filmed the chokehold arrest that resulted in the death of his friend Eric Garner. Many who identify as Latino see firsthand—and identify with—the epidemic of police violence that disproportionately beats, bruises and kills black bodies.

And yet at a national level the black-white binary—the widespread idea that race relations in the United States involve only these two groups—reduces the country’s 55 million Latinos to nonentities, left out of national conversations about anything except immigration and the frenzied pursuit of the “Hispanic vote.” Little national attention is paid to police shootings of unarmed Latinos, even though police in the United States kill Latinos at a higher rate than they kill whites—and the tallies are growing. Many in the nation rightfully mourn the loss of Michael Brown, Freddie Gray, Tamir Rice and Eric Garner but have never heard of Alex Nieto, a 28-year-old security guard killed by police while eating in a park in the rapidly gentrifying San Francisco neighborhood where he grew up.

The problem of unacknowledged police violence and the deaths of brown bodies is only the most immediate and violent effect of the black-white binary. Latino lives do not register in most of the nation’s majority institutions—including the media, which systematically erase Latinos from both Saturday Night Live and the Sunday political shows; philanthropic entities, which allocate about 1 percent of their collective giving to Latino organizations; and major literary prizes can’t seem to see Latino literary brilliance west of the Appalachians.

By focusing on Latinos only in the context of immigration, the media reinforce the deeply held notion that Latinos are foreign and hostile.

You’d never know it from the news media, which consistently equate “Latino” with “immigrant”—even though most people called Latinos are U.S.-born. By focusing on Latinos only in the context of immigration, the media reinforce the deeply held notion that Latinos are foreign and hostile. I write a lot about immigration, partly because of my immigrant family but also because editors operating within the black-white binary won’t pay me to write about much else. The possibility that we might have something important to say about race, climate change, war or class conflict remains just that, a possibility.

But frustration is beginning to turn into action. The tireless efforts of Refugio and Elvira Nieto, Alex Nieto’s parents, are one example. After a mostly white, suburban jury found four officers not guilty of using excessive force when they shot the unarmed young man 59 times, the Nietos led a crowded vigil, protesting their son’s murder and the twisted class and racial dynamics unleashed by Silicon Valley–led gentrification.

At the core of these digitized dynamics is the necessary (for gentrifiers, that is) erasure of Latino history, which enables gentrification and national amnesia, even in the massive part of the United States that was once Mexico. During the war in El Salvador, I learned that it’s easier for human beings to kill other human beings if they can first turn those human beings into “others,” if they can first take away their humanity. Growing up in pre–Silicon Valley San Francisco, I learned a similar lesson: you can’t displace an entire community without first dehumanizing and then erasing the memory of that community, for to remember would be to acknowledge the tragedy of living in a space that’s been ethnically cleansed for profit and hipster fun.

The need to give Latinos their rightful place in our history of struggles for equality could not be more clear.

But fighting the injustices of the present isn’t enough. We also need to complicate our country’s history. A new, more accurate historical narrative is being unearthed in the greater Southwest, where most Latinos live. Scholars are studying, for example, the myth of racially neutral “frontier justice,” revealing that in sunny California, from the Gold Rush into the 1930s, hundreds of Latinos were lynched in violent public spectacles chillingly similar to the lynchings of African Americans in the South. Tejano scholars are confirming stories told by elders in small towns in south Texas about the “Matanza,” the killing of up to 5,000 Mexicans by the Texas Rangers during the 1910s, stories of headless bodies floating in rivers and skulls found in the brush with holes in the backs of their heads.

The great brown hope of this research is that Mexicans and other Latinos will no longer simply play the role of foreign bad guys at the Alamo or tropical sidekicks in the civil rights stories told on plaques along roadsides and in historical exhibits and documentaries—the stories that shape our national identity. The need to give Latinos their rightful place in our history of struggles for equality could not be more clear, especially at a moment when Latino voters are offered this “choice”: a candidate who has openly supported jailing and deporting small children (possibly sending them to their deaths) who are fleeing a coup to which, according to leaked memos, she gave tacit support, and a candidate who launched his campaign with rhetoric that has already inspired violence against Latinos.

Better understanding and representing the Latino history of the United States not only gives more value to those lives by confirming their existence but also reorganizes our sense of national history, race and media so that the deaths and lives of the Alex Nietos of the world are given their appropriate weight in the national conversation.

Today, on the same coastal plains that hold the mass graves of victims of the Matanza, the remains of Central American and other immigrants are being buried in new mass graves. Latinos—as well as non-Latinos—who do not remember the past are condemned to repeat it.