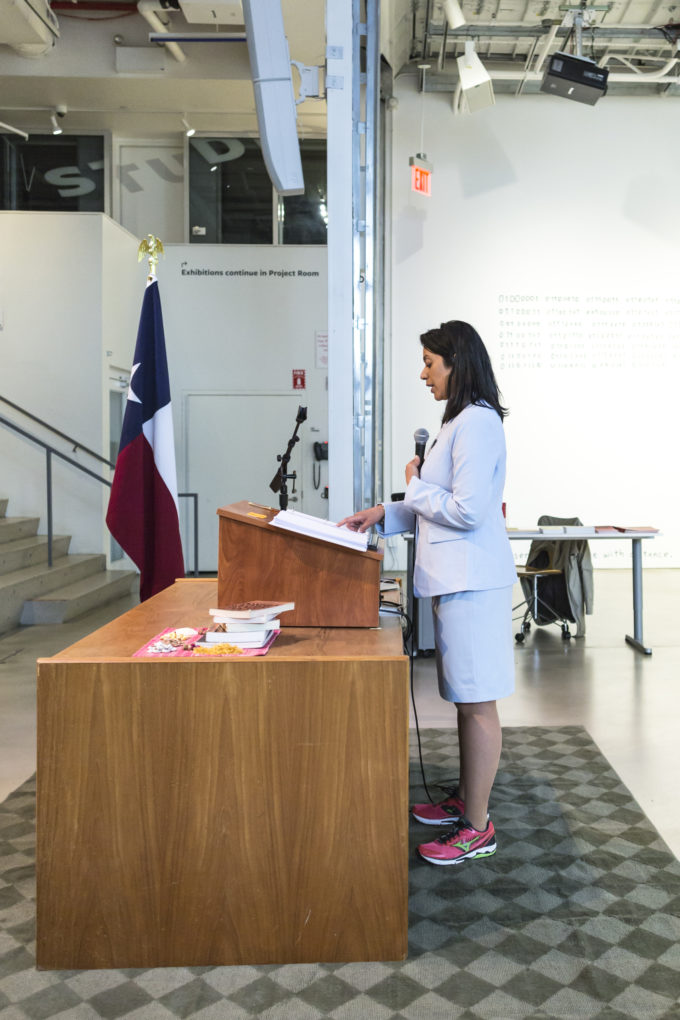

BRIC House. Alicia Grullón, Filibuster, April 13, 2016. Photo by Angelys Ocana.

I remember crowding around a laptop with friends to watch Wendy Davis’s filibuster in the Texas State Senate. Her eleven-hour speech was an attempt to block a bill imposing restrictions that would cause many abortion clinics to close. Even on a tiny computer screen and halfway across the country, you could feel the energy and tension in the statehouse, all the way up until she completed the filibuster, to the raucous chanting of supporters that filled the statehouse hallways. So when I heard about Alicia Grullón’s reenactment of the filibuster at BRIC House as part of the exhibition “Whisper or Shout: Artists in the Social Sphere,” I wondered what it would be like to see a a reenactment of a moment that had already been so well documented.

Grullón’s performance piece was urgent and moving. Hearing the text of the filibuster spoken aloud by someone who is not a lawyer or a politician gave the words new weight, and it was striking to see Grullón in person, dealing with fatigue as well as the often openly hostile environment. After her performance, we talked about how she came to incorporate reenactments into her artistic practice, what it means to change the identity of one of the actors in a political moment, and the radical empathy of putting yourself into someone else’s shoes. On June 17th, Grullón will perform a reenactment of Bernie Sanders’s eight-and-a-half hour filibuster of the Bush tax cuts, as part of the Of the People exhibition at Smack Mellon in Brooklyn.

Creative Time Reports (Rachel Riederer, associate editor): How did you start to do reenactments as a part of your artistic practice?

Alicia Grullón: It comes from needing to document and thinking of different ways to document. I started off in a Drama BFA and realized I hated it. I didn’t hate performing, but just everything that went along with it: auditioning, casting, needing to rely on others to do something. You need a place, a writer, a director etc.—I wanted to be more self-sufficient.

So when I made the decision not to pursue acting anymore, I started thinking of other choices, which went back to my interests, mainly photography. Being trained as a photographer and looking at photography’s practice, process, and traditions I see I have always had a need to document. I think these questions come up with my reenactments: How can I document with my body through performance? How is this different from traditional forms of documenting?

CTR: What was your first reenactment?

AG: My first reenactment was Illegal Death, in 2007. That was in response to an undocumented worker from Honduras who was found frozen to death in the forests of Long Island in February of 2007. Temperatures had dropped to about minus 2 F°. The area where he was found was very close to an LIRR train station. What stood out the most for me was the absence of dignity and the loneliness. This city has a huge homeless population and many have died on the streets in the same manner.

CTR: How did that work? Were you reenacting the process of freezing and dying…?

AG: I staged the reenactment in Van Cortlandt Park in The Bronx. It was a couple of weeks after the incident, and there was snow on the ground. I went into the forest and looked for a location that would act like shelter if I were to be in that situation. I took some things with me—a backpack and the documenting gear I needed. There was a fallen tree with branches around it forming a hut-like structure. That’s where I set up.

I had intentionally chosen an area away from walking paths but still relatively near to one. My idea was to follow as closely as I could choices he might’ve made not to be found, be safe and still within reach. This may have been pragmatic. Perhaps he was close to the LIRR station in order to get to work. The path from me was barely visible. I watched it as laid in the snow for about two hours or so, cold. No one passed by. It was winter and people were indoors less likely to go out for a walk.

In 2010, I was asked to re-stage the piece for the Bronx Latin American Biennial at the Bronx Museum of Arts. I set it up on the balcony with the same idea: “How could I re-stage it here on the balcony of the museum if I needed shelter?” I collected branches and leaves from the area and set up a found wooden pallet. I laid on the balcony for about 4 hours. It was early autumn so it got chilly at the end of the night. The following year I re-staged it again for El Museo del Barrio’s S-Files at Socrates Park. Each time it changed a little bit. At Socrates Park, I set up a little fire pit, had a cooler with some religious items in it and a few blankets. I laid there for 4 hours as well.

CTR: You’re literally putting yourself in other people’s shoes. It’s a radical act of empathizing and relating. How do you feel at the end of one of these reenactments?

AG: I’m exhausted. Each one is different though. For Illegal Death, I really wasn’t talking, so I was very much aware of my body. Being able to be motionless and focus on my breath impacted me the most.

Being able to be motionless and focus on my breath impacted me the most.

No Cookies, was much more engaging. I reenacted the ten-month strike of Stella D’Oro workers in Kingsbridge in the Northwest Bronx and their striking of a Wall Street corporation, Brynwood Partners, which bought the company in 2006.

Stella D’oro had provided real working wages, insurance and pensions—everything that we want to provide our workers with. People were sending their kids to school and they were thriving. When Brynwood bought the business, they refused to provide these benefits. So workers struck. They were out there in the rain and snow everyday. The case went to court and the workers won. After 3 months, Brynwood sold the company and operations were shipped to South Carolina.

When I did the reenactment, the strike had ended a year earlier and the factory had closed down. I recreated some of the signs I had kept account of and made cookies. It was interesting to have people pass by and say, “Yes!” Go!” Some didn’t realize the strike was over and didn’t know the results of it. At some point I did tell them. Some Stella D’oro workers who still lived in the area came out and participated. They told me their stories.

I grew up in the area so for those ten months, I saw people fight to keep living with a bit more dignity—that experience was tremendously empowering. Doing No Cookies was different from Illegal Death because I was talking, moving around and getting fired up about issues on neighbor’s minds. It was very thought provoking. I had conversations on what changes could take place. We talked about worker’s rights, our changing neighborhoods, and what that meant. It was also fun at the same time—offering people cookies getting their attention and having them talk. It was more hopeful and social.

It wasn’t Illegal Death, where the solitude was immense and it weighed a lot and it was hard to talk afterwards. After the doing it at the Bronx Museum, my childhood friend waited for me. Reengaging again with another human being was difficult.

BRIC House. Alicia Grullón, Filibuster, April 13, 2016. Photo by Angelys Ocana.

CTR: That’s interesting because in Filibuster, you’re engaging with other human beings through recordings. What was that like?

AG: Goodness that was all about the moment. I didn’t rehearse it.

CTR: You didn’t? I just assumed that you had. I watched a lot of the Wendy Davis filibuster and a lot of your cadences were so reminiscent of hers.

AG: I watched the recording many times and I guess that’s the difference between theater and performance art. You’re not meant to rehearse it; it’s meant to happen. That’s something that I’ve always identified with. The improvisational parts of performance, just being there and letting the words take you where they need to go. She didn’t rehearse. She just wrote it. She’s a lawyer, so she can spew out specific legalities like nobody’s business. I cannot.

I was there and reading it, responding to some of the dumb things that were being said by the conservative state senators in opposition. There were very much gut reactions for me. After having read the testimonies from families—and knowing the law more specifically, it’s kind of like a video camera zooming in and the feeling becomes that much more heightened.

CTR: I had forgotten about the parts where legislators were threatening her with jail time.

AG: Yes and it was a quite dysfunctional moment to threaten her with that. I think right after that, Senator Deuell used the specific words of, “I’ll let you”. He changed his verb from ‘let’ to ‘go ahead’. This goes back to the patriarchal control of everything; especially white, male control over situations. For me, that was a very present and large part of what fueled me to do the filibuster. Yes, it is a women’s issue. When you highlight and focus on women of color, you can’t just deny all the choices that have been made to deny us access to life. That’s quite a contradiction to what these senators are promoting.

CTR: You have mentioned the idea that having a woman of color—instead of a white woman—in this position transforms the experience. Can you talk about that?

AG: It goes back to that absence in dialogues about feminism. It goes back to recognizing that there have been many women’s voices that have been left out of this greater dialogue. I think that is one of the reasons why the feminist movement in the past wasn’t more, because of the absence of women of color’s experience as the feminist experience. Feminists didn’t deal with the signification of race here. When we deal with pro-choice measures, we also have to think about things like forced sterilization and experimentation. Women of color did not have a choice in those instances.

The set of reproductive choices that one woman may have because of her economic and/or educational freedom is a different set of choices for someone else that does not have those choices. For me, the filibuster is one of those moments where that absence is made very present.

CTR: I noticed that you had a copy of Angela Davis’s Women, Race & Class. Can you talk about that stack of books you had? Were they something you added?

AG: It was something I added. Angela Davis has a whole chapter devoted to reproduction rights. She takes us through a history of it in that particular book. The other books were Art on my Mind by bell hooks, Coco Fusco’s The Bodies That Were Not Ours. All these women write about that absence of women of color in larger discourses of art, politics, culture, and history. They’ve always been inspiring for me, got me through graduate school and I thought it fitting to have them there as my resources other stages on feminism that has always been.

CTR: It’s really nice to think of that particular set of people being right there with you.

AG: That’s as close as I’m getting to them. [chuckle] It was comforting, in a way, to think I have these great thinkers’ books on my desk and their books are their way of filling in the absence. They’re very much there and not apologetic about it in any way.

CTR: You had some other objects up there on the desk beside you as well. What were those?

AG: There were cowry shells, and corn and beans and rice, marigold leaves, jasmine buds and rose buds. These are medicinal herbs and cultural connections for me. They represent other women’s voices and histories I wanted to have with me on that day. Many women are persistently absent from these dialogues because of institutional economic, class, and educational structures. They’re pushed aside and not acknowledged but are very much part of the experience and history.

CTR: For the filibuster, how long was the performance all in all?

AG: It was from 10 am – 9 pm. I finished at nine and it was eleven hours. I only looked at the clock twice because I had to look up for a second. We ended at the eleventh hour.

CTR: I’m curious about the experience of standing and talking for eleven hours. It sounds like you really engaged by not watching the clock. Were you exhausted or was it giving you energy?

AG: There was a point where my shoulders hurt a lot. I had a nice conversation with Wendy Davis in preparation for this. She was very supportive with her time. It was an incredible twenty minutes of my life talking to someone I admire. I remember she said there was one point where she was especially fired up. At that moment, time just flew for her. There was a moment where I thought, “This must have been it.” It was the second attempt to derail her. After that it just felt like I flew and I didn’t want to stop.

BRIC House. Alicia Grullón, Filibuster, April 13, 2016. Photo by Angelys Ocana.

CTR: Did you feel like it was a challenge to stay focused that entire time or did the material keep you in it?

AG: The material certainly kept me in it. That’s the incredible thing about this particular filibuster; it takes you through all of these different perspectives on this issue. It’s a women’s health issue, it’s an issue of accessibility, it’s an issue of class, and it goes back to the issue of race.

It’s a women’s health issue, it’s an issue of accessibility, it’s an issue of class, and it goes back to the issue of race.

I had to be alert because there was legal terminology that was really difficult. I had to make sure I was making sense—if something I said wasn’t making sense to me, I know it really wouldn’t make sense to other people.

CTR: In the part that I saw, there was this huge emphasis on the part of the male senators who were giving comments—almost an obsession—on keeping the tone collegial. They prefaced everything by saying how much they appreciated the nice tone that everyone was maintaining. It struck me that it was this weird denial of the fact that they were in combat with each other. That tone changes a lot over the course of the eleven hours.

AG: They had to keep civil. It’s funny because when Senator Davis is called out, it seems that they just want her to stay in her place because she’s a woman. As a woman of color, it’s a doubly “stay in your place” message. Their needing to keep a nice tone and demeanor comes across as arrogant and comical at some point. I don’t know if it’s cultural, but it’s funny that you pointed it out because no one is really being nice.

I think the only person who was actually civil towards her was Senator Lucio. Their interaction was quite moving. We know he voted for the bill because he’s a Catholic and pro-life. She went to the extent of saying that he was her dearest friend and colleague in senate and the bill was the only thing they’d disagreed on. Everyone else was just calling her out on things unjustifiably.

CTR: The condescending tone of the questions is really striking. I wonder if you were thinking about modulating your responses in a certain way. In terms of tone, were you tempted to fight back more? There is this weird disconnect between the commenters tone and the content. I’m wondering how you experience this on your side by reading the material and responding to their voices.

AG: In a sense, it’s still playing the game. Even though you want to tell them to piss off, you can’t. I know she couldn’t. You’re still at your job, and this is part of your job. We’ve all had moments where someone says something condescending, mean or flippant. It’s the workplace so you can’t really say “You’re a jerk” although you’re thinking it. That was the adrenaline that kept me going and kept me focused: Knowing to keep our decorum and respond in a way that promotes more dialogue that’s actually getting us somewhere. We want to say these things, but at the end of the game it just makes us angry. How are we going to get point b?

CTR: Do you have plans to take this performance elsewhere?

AG: No, I don’t think so. This may be a once-in-a-lifetime kind of thing. Senator Davis isn’t going to do this particular filibuster again.

CTR: It’s a pretty incredible feat.

AG: It’s incredible to have completed it. I’m very grateful for having been invited to participate in this show. I think all of the artists address very pressing issues in different ways and are trying to promote more dialogue. It’s very timely. Everything has changed. There are movements all around the world led by everyday people pushing progress forward. Seeing that art is a tool is very important to understand in order to access dialogue and action. We’re compromised everyday and need to be pushed to really change how we live and are in this world. I think that all of us in this particular show are trying to present the alternatives.