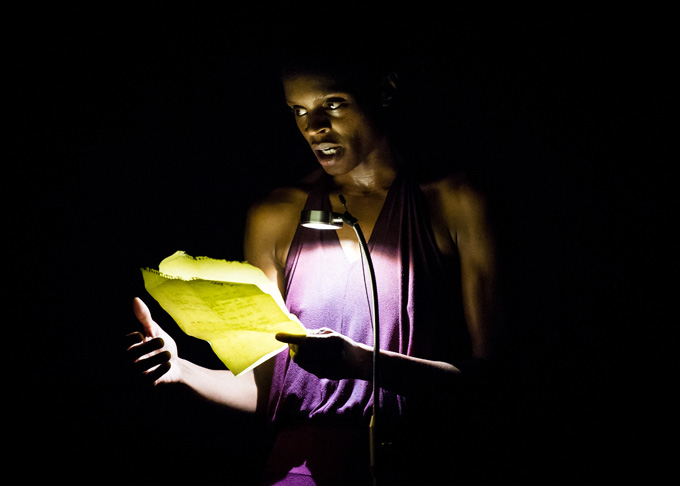

Photo by Izzy Zimmerman. From Bronx Gothic: The Oval, LMCC River to River Festival 2014.

Okwui Okpokwasili is no stranger to stamina. The performer, writer and choreographer has been known to start a performance with over thirty minutes of impassioned physical movement before even uttering her first word of dialogue. Earlier this year, Okpokwasili was selected by The Times Square Alliance, in partnership with New York Foundation for the Arts, for the fall “Residency at the Crossroads” program in which she and her longtime collaborator, Peter Born, will take to Times Square and create a song from encounters with passersby on the iconic junction. I caught up with Okpokwasili to talk about her practice and how she came to see the body as the place, the message and the way that she wanted to communicate.

Creative Time Reports (Marisa Mazria Katz, editor): You once wrote that you think “primarily about the body, and the body in relationship to a body of witnesses, a body in the process of becoming unknown to itself. The brown body and the accumulated readings that position it within a cultural constellation of desire, pathology and pain.” That’s a beautiful passage. How would you characterize the relationship with your body as a performer?

Okwui Okpokwasili: The body is inescapable, and as a performer there is an awareness that you have to have about what your body is doing. You have to really sharpen a proprioceptive sense—what is happening externally and what is happening internally for me and what my body is signaling to people watching me.

I’m interested in how brown bodies are read, how anger might be placed on the body but not pain, sadness and vulnerability. How is an internal sense of self and an internal psychic condition articulated? How is that articulation received? There is a space where what I mean and what I say with my body may not be what a viewer understands, and that’s interesting to me, a zone where multiple meanings are in a dynamic and charged exchange. How do I unmoor some of the common readings of the brown body? But then how do I not only resist readings but also use and acknowledge them?

CTR: This seems to be a place where your practice almost resides.

OO: There are practices that I engage in which I actually stop being concerned about controlling how my exteriority is read. My primary concern is to find a practice that serves as an engine for the performance so that I’m not initially concerned about external forms and signs, but I discover and develop the internal conditions of the character in the piece. How do I find the practice to shape the body beginning with an internal practice and let go of an attempt to control its outward form, what it looks like? So that’s one of the things that I’m interested in doing. I spent some time at Body Weather Farm in Japan, founded by Min Tanaka and his collaborators. While I was there, I found that what we were doing was a practice of sensation, how to allow the body to be in a deep and intentional sensory relationship to the land. The movement practice in the workshops would sometimes directly relate to what your body was doing while farming. We worked on sensation, the sensation of wind, the sensation of moving through streams. You moved, and you watched. And when I looked at performers, I had no idea what imagery people were working with and what their internal sensations were, but I was aware of myself projecting meanings and ideas onto bodies. I also tried to be attentive to my feelings of wonder when I encountered a lovely confusion when bodies would refuse to remain fixed in one meaning or reading. It was clear to me that I’m always reading bodies through my own lens. And then I asked how I could also try to make a space for that, to make a space so that people can think I’m doing something, but also have an awareness of themselves that’s projecting their own ideas onto the forms and shapes it might be taking.

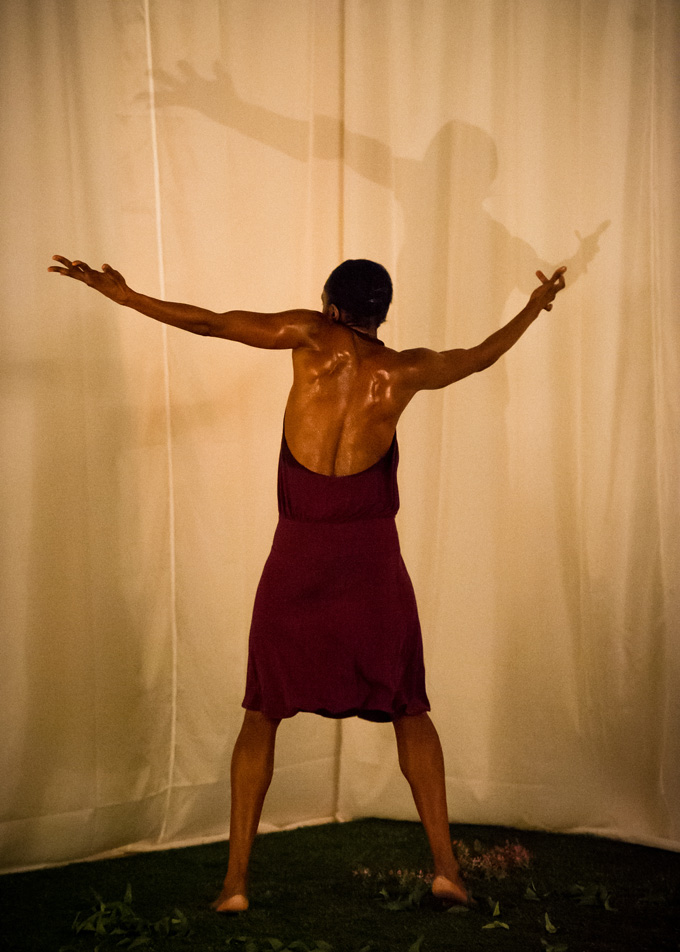

Photo by Izzy Zimmerman. From Bronx Gothic: The Oval, LMCC River to River Festival 2014.

CTR: In terms of your body and working, one of the powerful parts of Bronx Gothic for me was the 30 minutes you spent moving before you say the first word of dialogue. How would you say that informs the performance? How did you conceive of such an intense commitment? I don’t know that I’ve ever seen anything quite like that.

OO: I saw Min Tanaka do his work in Performance Space 122 on the Lower East Side in the 1990s, and he seemed to understand “time” as mutable material and as space—the speed at which I think things should normally happen was not the speed at which it was happening. I’ve always been interested in this idea of time and how long it takes for the audience to come to be in the time that you are in.

I have also worked with Ralph Lemon quite a bit. I feel like there are ways in which he pushes the audience in terms of when they think something should end and when it does end. What do you need to do as an artist to change something for yourself in the body physiologically, and then what do you need to do? How long do you have to keep doing that so that can start to happen to the audience? I’m just really interested in what I consider to be these strange, almost imperceptible but very deep shifts that can happen.

CTR: What happens when you go to that space?

OO: I feel that I am no longer in a place that I know. And whether that means that the space is dressed in an interesting way and shifted from a normal theater space or whether that means I’m looking at something and I don’t know what I’m looking at. Of course, we live in a time when we have lots of information; I get whatever I want as quickly as I want it. And what happens when you go into a space, into a live space? My question is whether we could have a different engagement, a different contract with one another in which maybe you’re not gonna get what you want and definitely not as quickly as you want it.

CTR: So in a way the live space over the past decade (with the advent of smartphones) has taken on a whole new meaning.

OO: I think so.

CTR: I wanted to talk about Poor People’s TV Room. It is very similar to what is at the heart of Creative Time Reports: getting artists to weigh in on what’s happening in the news. I was really struck by this project and how it came about. I loved what you said about how the Bring Back Our Girls campaign inspired the project: “Why was I surprised that the voices of the indigenous Nigerian women who sparked a movement were erased under a swarm of celebrity Twitter feeds. Can I undermine that erasure?” Can you talk a little bit about what you said and how the project speaks to that?

OO: There’s a part of me that feels like the erasure is actually inevitable and perhaps in another Twitter feed we’re all being erased, you know? And that’s OK. However, I guess it did, for me, spark again this need to go excavating, to undo the erasure against all odds and all reasonableness. It started around the time when the Bring Back Our Girls movement happened following the kidnappings of the Chibok girls by Boko Haram. I believe there were around 300 kidnapped, and 70 ran away. The movement began with a group of Nigerian women determined to expose the ineptness of the Nigerian government in protecting these schoolgirls and what appeared to be total disinterest in getting the girls back. I was impressed by how this self-advocacy is in direct contradiction to narratives of African women being victims. The ability of the indigenous women—along with some other pretty powerful women (like the person who started saying, “Bring back our girls,” who actually happened to be the vice president for the World Bank’s Africa Region, a woman)—to spur an international outcry moved me. I do think that there were some men involved in the movement too, as well as all the mothers of these girls, who were fighting to get someone to see the madness that this many girls can just be taken, stolen, and the government is doing nothing. To me it was powerful, especially in the face of a government that was sometimes denying that this had even happened.

Look at what these African women did. They’re not just victims, right, they are active advocates for their own liberation, their own struggle. And I started to think, it’s not even new. There’s a legacy of this. In the southern part of the country there is a history of collective action and embodied protests. And I started to look into something called the Women’s War that happened in 1929, and I was able to find reports on people who were speaking about what was going on, women who were involved. They were protesting what they thought would be their taxation by the colonial government. And in the course of their protests, I think there were at least 50 unarmed women who were shot and killed. I was also really interested in the forms of the protests. They would threaten to reveal their naked bodies. They would make collective songs of grievance. They would go to the representatives of the colonial government, the homes of those representatives, and they would sit on them. They would sit on a man, which means that they would sit in the compound, in a gated area, and inside of this area is the man’s compound, and they would go in and sit and sing all of the bad things about this person.

CTR: What would they do once they got inside the compound?

OO: They would just sort of stay there and make them miserable until they had to concede and give up. I think that all of that is incredibly powerful, and these embodied protests keep happening. I was looking at some examples. In 2002 a group of women in the southern part of Nigeria, around the delta region, were holding the employees of a Shell station hostage. They held about 700 people hostage and also threatened to bare their naked bodies in order to get Shell Corporation to accede to their demands, some of which were cleaning up pollution and making sure that people in the villages had jobs and that the company was doing something to acknowledge that the resources are coming from these indigenous people.

CTR: Next up you have your Times Square Arts residency.

OO: Yes, that’s Poor People’s TV Room and some of the embodied practices, particularly this kind of collective song that I will be generating. I’m so curious about what that can be. I feel I can use Times Square as a deep well or resource to see what sort of information people want to share, in particular if it could be shared in a song. If they could say something to the world, if they could have their voice be amplified, what is the thing that they would say? Times Square is such a strange place. It’s just an interesting intersection of commerce and at the same time a place where people have gone collectively to watch debates. Black Lives Matter has been through there. I just think it’s an incredible history.

CTR: And your plan is to explore the “common cry,” or the ideas and desires that emerge from these comments of people in Times Square?

OO: I don’t necessarily want it to just be maudlin. The world is on fire. Some of us feel that, but not everybody feels that. I wanted to see if I can ask some questions to get at some kind of common concern or condition. Or is everything so wildly divergent? Maybe that’s just impossible; there’s no way that can happen. And then I want to see if I can construct a song and share it with people again.

CTR: And how does Peter Born, your longtime collaborator, fit into all of this? How will you guys work together?

OO: He will design the space that I’m going to be in because part of my desire is to not seem overly solicitous. I don’t want to be roaming around asking people things; I want to have a base and hopefully make it interesting enough that people will come or be drawn toward it, and then I can kind of snare them in. And so Peter will be designing the space because that’s generally what we do together. We do porous things. I’ve been going over questions with him, and we have our arguments about how much of a conversation I am going to have. What’s working, what’s not working. We want to help establish the relationship between me and whoever comes in. And we are asking, “What space can facilitate the kind of relationship we want?” And then he’ll probably be with me as we try to construct a song together.

CTR: In some respects it feels like people are being heard more than they’ve ever been before—they can now comment on articles in unprecedented ways, share their thoughts on Facebook and Twitter—and with this project you are working on negotiating that in real time. We have to listen to our audiences. There’s a negotiation that’s happening. And you’re bringing it here in the moment.

OO: There’s a lot of mask work online. Sometimes you can read what’s sincere, and then sometimes it just feels like there are people trolling, which is something I don’t even understand. It is along the lines of throwing a bomb into a room and watching people kind of sputter and come apart. I almost feel like that desire is mostly fed only when you’re alone. It’s like you have to be a psychopath to really throw a bomb into a room. And there is something weird about how the internet allows everybody that little secrecy. I just think there’s something about being with somebody and being embodied with each other. It can be quite fraught and strange.

CTR: How do you respond to the physicality of the person you are interviewing?

OO: Someone says something, but then they move their head a certain way, and I am given more information; they are distracted or they come in to listen more closely. I had an interesting conversation with a couple in Times Square, but even when we were talking, there were certain ways that their body language seemed to belie some of what they were saying. I wanted to believe that they were having a really good time, but I don’t know if it’s about me asking these questions and trying to force some intimacy that’s uncomfortable. I’m gonna have to figure it out: How do I help people say what it is they want to say and not what they think they should say. And how do I read people? How do I even read authenticity? How do I know anything at all?

Photo by Ian Douglas. From Bronx Gothic, Danspace Project, COIL Festival 2014.