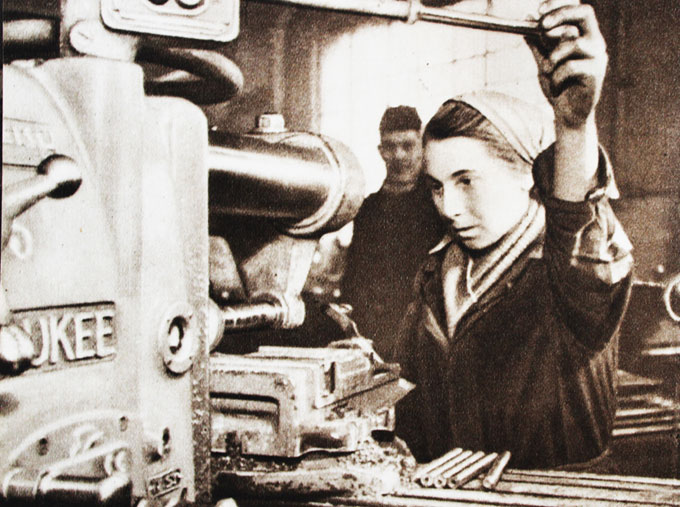

Reconstruction of the country, metallurgy. 1948.

“You abolished our organization! Our men are free to go everywhere, go hunting or drinking. That organization was the only place where we were allowed to go, where they couldn’t prohibit us from going. And now you abolish even that!” When Neda Božinović, a Communist Party official from Serbia, visited Bosnia and Herzegovina in the mid-1950s, she encountered a group of angry village women voicing their disappointment about the dismantling of the Antifascist Front of Women (Antifašistički Front Žena, or AFŽ), an organization that operated from 1942 to 1953 in the former Yugoslavia. Though the AFŽ has been largely forgotten, it was once an extremely important organization for individual women and for the country, helping to expand the possibilities that the women of Yugoslavia imagined for their lives.

During a time of war, issues of defense, freedom and a country’s independence become everyone’s issues; women too become part of the struggle against war and fascism. In April 1941 the kingdom of Yugoslavia was occupied by Axis forces and divided between Hungary, Germany, Italy and Bulgaria. Yugoslav Partisan forces, under the control of the Communist Party and led by Josip Broz Tito, started Yugoslavia’s resistance movement and grew into the organized National Liberation Army (NLA). With great support from the women of the AFŽ, the NLA got recognition from the Western Allies, which helped Yugoslavia gain freedom and autonomy.

Delegation of AFŽ welcomes Maria Šaričeva, chief delegate of Soviet women. 1948.

The mobilization of women, one of the primary tasks of the AFŽ, was happening at a steady pace; it did not take long before every village, town and county in Yugoslavia had its branch.

At the founding of the AFŽ in December 1942 in Bosanski Petrovac, Bosnia and Herzegovina, President Tito addressed the assembly, welcoming 166 delegates from all parts of Yugoslavia: “Women, my comrades, have passed the maturity test; they have shown that they are capable, not only to run households, but to fight with guns in their hands, to rule and hold power in their hands.” These words, multiplied in various forms, echoed throughout the entire country, reaching women of all social backgrounds. The mobilization of women, one of the primary tasks of the AFŽ, was happening at a steady pace; it did not take long before every village, town and county in Yugoslavia had its branch. By the end of the war more than 100,000 women had participated in the NLA as combatants, nurses, couriers, cooks and delegates. Others acted in the background, running the country’s economy, managing production and distribution of food and healing the wounds of war.

Women from Kordun carrying food for partisans. Year unknown.

Women’s contributions to the struggle for liberation were legitimized after the war, when the women of Yugoslavia were given the well-deserved right to vote. In 1946 the equal rights of men and women in all state, economic and sociopolitical life were inscribed in the new constitution of the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia. The AFŽ grew into a well-organized structure headed by a central committee that oversaw and managed the work of local, village, municipal, district, county and provincial committees, and after a short period of autonomy it was absorbed into the People’s Front / Communist Party. The organization’s postwar activities included reconstruction of war-torn Yugoslavia, humanitarian activities and the cultural and educational empowerment of women. In fact, the empowerment of women and the modernization of women’s lives complemented the prevailing socialist idea that the degree of a society’s civilization is measured by the position of women in that society.

Left: Reconstruction of the country, railway, working action of women. 1948. Right: Harvest. 1942.

One of the AFŽ’s most important tasks was organizing and implementing literacy courses on a massive scale. As a result, just one year after the war, 400,000 women learned how to read and write. Educated urban women were sent to rural areas to exemplify emancipation and encourage the wider engagement of women in all civic matters. In addition to literacy courses, the AFŽ offered lectures on history, politics and economics, as well as practical lessons concerning hygiene and health, work and motherhood. By organizing public kitchens, communal agriculture and kindergartens, the AFŽ supported the implementation of Tito’s five-year plan for postwar reconstruction and development. Masses of women gave countless hours to state-sponsored volunteer work building roads, factories and railways in the new socialist Yugoslavia.

Literacy courses. 1948.

Through this state-sponsored volunteer work, women entered the public sphere. Though they took on these new roles, they never left the private sphere, where their primary roles were still those of mothers and caretakers. The involvement of women in the political and decision-making processes of Yugoslavia was limited and did not reflect the degree of their participation in World War II and postwar reconstruction.

Meanwhile the implementation of Tito’s five-year plan soon became too costly. The newly established system of “workers’ self-government,” in which workers’ collectives took over the governance of state-owned institutions, reduced the need for a massive workforce, especially for less qualified female workers. By introducing high child subsidies that encouraged people to have more children and simultaneously reducing public child-care services, the government directed women back to their homes and to the private sphere. The AFŽ was dismantled in 1953 as there was allegedly no need for a separate organization.

Textile industry, 1948.

It comes across as science fiction: imagine two million women today, working together for common goals. It seems quite unimaginable.

The dissolution of the AFŽ marked the end of the golden era of Yugoslav feminism. Even though feminism was at the time considered a bourgeois concept, one cannot but interpret the movement as feminist par excellence. The work and relevant achievements of the organization represent incredible progress in women’s emancipation and social emancipation in general. Yet in official histories such as school textbooks and political narratives, the story of the AFŽ is absent, and so there is little public knowledge of the organization. As a matter of fact, it comes across as science fiction: imagine two million women today, working together for common goals. It seems quite unimaginable.

Aspiring to make known the historical facts and to preserve and affirm the emancipatory heritage of the AFŽ, in 2011 the Association for Culture and Art CRVENA in Sarajevo started a transdisciplinary research project called What Has Our Struggle Given Us? The title takes the name of a popular partisan song and turns it into a question. The project includes the collection and archiving of documents related to the period and the production of new artworks based on those findings. On March 8, 2015, CRVENA launched the online Archive of the Antifascist Struggle of Women of Bosnia and Herzegovina and Yugoslavia. The archive comprises five collections: periodicals, audio, books, documents and photographs. It is constantly developing and is envisioned as an ongoing program with different phases and structures, varying from research and data collection to production of new knowledge and artistic and cultural interventions. By reviving the bonds with the past, common to all countries of the former Yugoslavia, the archive not only defies cultural amnesia but also generates possibilities for new and responsible forms of action.

Today’s women’s movement, fragmented and dependent on the neoliberal politics of NGO support and funding, suffers greatly from a lack of transparency, coordination and unified work, the qualities that so strongly characterized the activities of the AFŽ. It was an impressive achievement to organize such a large movement of women, and looking at the structure and dynamics of the AFŽ might give us ideas for how we can do something like this again, even in today’s challenging sociopolitical circumstances. This is why the archive is about learning, imagining, doing, and most importantly believing that women in fact did and can make revolutions—and that the time is right to start new ones.

Left: Reconstruction of the country, women working in fields. 1948. Right: Reconstruction of the country, working action of women. 1948.

This piece was made possible, in part, thanks to the generous support of the Trust for Mutual Understanding.