On April 13, 1975, a group of Christian militiamen opened fire on a bus full of Palestinian refugees, killing all its passengers and initiating a chain of deadly battles between Christian nationalists and the PLO and its leftist and Muslim allies.

I was six years old when Lebanon’s civil war started. During the “events,” as they were referred to, which preceded even the bus massacre, my mother survived a bullet fragment to her head. It was not long until my parents made the decision to leave Lebanon for a few days in the hope that the situation would soon improve. Little did I know that the fighting would continue for 15 years and that my parents’ choice to leave would determine the rest of my life. I grew up between Cairo, Paris and London, moving back to Lebanon only in 1994, when the country was in the early stages of a long process of recovery and reconstruction.

The Arab Image Foundation (AIF) was founded in 1997, contributing to a broader movement to foster cultural memory and critical analysis in the Middle East by discovering and preserving the photographic heritage of the region. For me, becoming a member of the AIF at the moment of its inception was also part of a personal journey of reconnecting with my origins. Stepping into the past to collect archival images was an instinctive undertaking in the face of precarious post war times. I felt drawn to these images documenting a history that was contested and raw—still in the making.

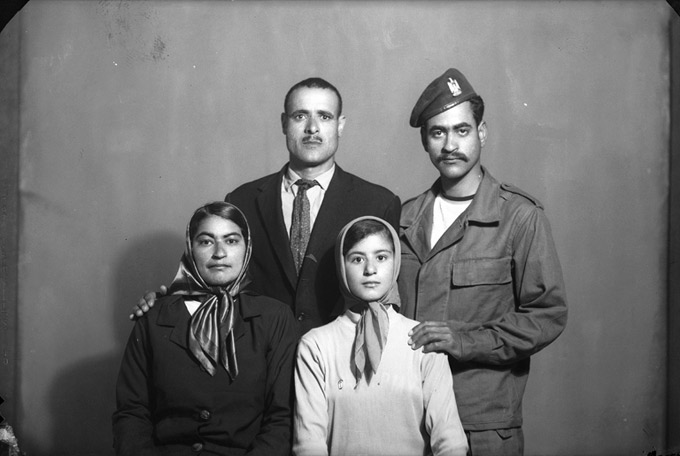

Members of the Palestinian resistance and family, 1980. Photo by Chafic el Soussi. Collection AIF/Chafic el Soussi. © Arab Image Foundation.

One day in 2005 a massive truck bomb from a passing motorcade exploded underneath Starco, an iconic building in downtown Beirut where the AIF was located. Although the archive’s office was on the top floor, its windows were shattered to pieces while the then-director, Zeina Arida, and her assistants were working. Rafik Hariri, the former prime minister, had just been assassinated.

Hariri’s assassination and the events that followed reminded me that our efforts to archive aspects of Arab history, including the Lebanese civil war, were not a straightforward task. The material damage to our office revealed the vulnerability of our collection and suggested that the civil war was not really over.

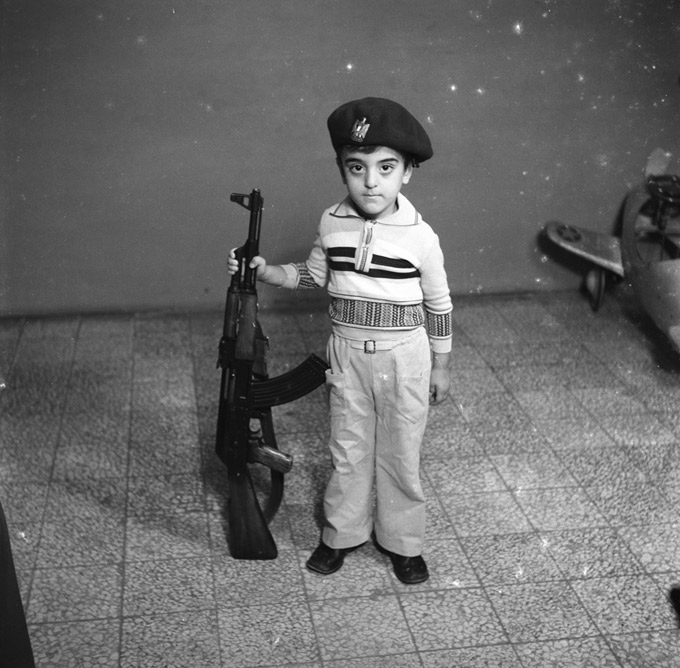

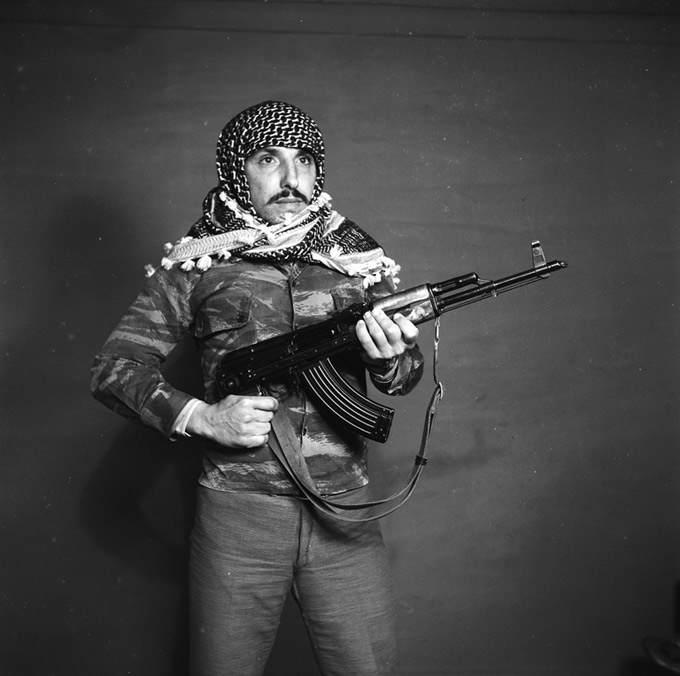

Palestinian Resistance. Studio portrait, 1967. Photo by Hashem Madani. Collection AIF/Hashem Madani. © Arab Image Foundation.

For many years mounted studio photographs portraying Palestinian resistance fighters greeted visitors at the entrance of the AIF’s office. Palestinians played a significant and too often forgotten role in the early days of the Lebanese civil war. To me, these images of fedayeen were emblematic of the visual culture that often served to frame an ideologically fractured Arab world, giving form to its various political factions, cultural identities and currents of self-determination. These black-and-white prints of fighters, an integral part of my experience of the AIF, were quintessential images of the past. Or so I thought. After Hariri’s assassination I looked at them differently. They reflected the need to think of the war as a series of ongoing conflicts rather than as a closed chapter of a recent past.

Zarif, Palestinian resistance fighter, 1970-1972. Photo by Hashem Madani. Collection AIF/Hashem Madani. © Arab Image Foundation.

Indeed, since the AIF was founded nearly two decades ago, it has been the organization’s policy to build a collection through artists’ research projects so that the images remain singular, never resolving into a fixed identity, temporality or ideological representation. The idiosyncratic collection that has resulted, which is multifaceted enough to contain archetypal images of war and resistance alongside vernacular photography and often humorous portraits, counters the West’s orientalist visions of the region and Arab nationalist clichés alike.

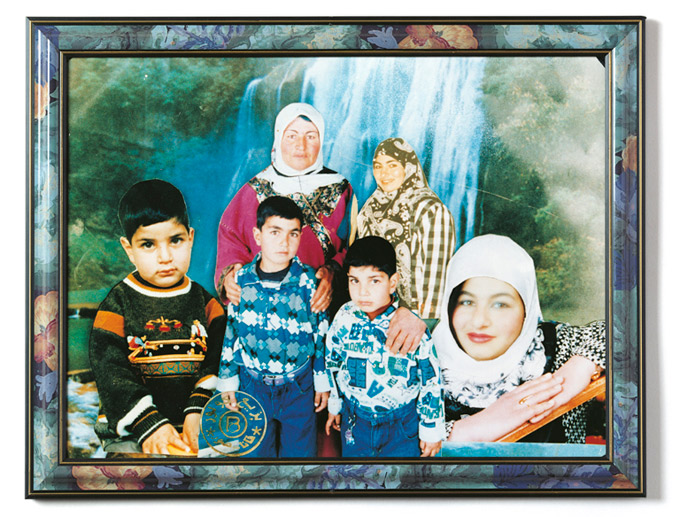

Photographs from the AIF’s collection infuse many of my own photo-collages and installations. In early 2006, as I was researching the iconography and social construction of paradise (and its loss), I selected portraits from the 1996 Qana massacre, in which more than a hundred Lebanese civilians were killed by Israeli shelling. The photos of the victims were cut and pasted by their loved ones onto landscapes of natural beauty, with waterfalls and mountains, and enshrined in golden frames. They seemed to answer my quest perfectly.

Portrait of victims of the Qana Massacre on the 18th of April 1996. Anonymous photographer. Collection AIF/Doha Shams. © Arab Image Foundation.

Perfumes & Bazaar, the Garden of Allah (2006), a large-scale digital montage in which I included some of the AIF’s Qana images (researched and donated by the journalist Doha Shams), is essentially a portrait of my mother. She poses in front of baroque furniture in an illusionary living room inspired by photos from the 1970s of our lost home in Lebanon. Behind her the walls have disappeared to reveal a “garden of Allah,” a bucolic landscape inhabited by portraits of the martyrs from Qana and other images. During the summer of 2006 the south of Lebanon—including, once again, Qana—was devastated by Israeli attacks that left more than a thousand dead and utterly destroyed the area’s infrastructure.

Lara Baladi, Perfumes & Bazaar, the Garden of Allah, 2006.

Over the years the AIF has not only grown and preserved its own collection but has also become a “mother of archives” and adviser to private and institutional collections in the region. As part of that additional role, the AIF has been helping to evaluate the work needed to preserve the collection of Beit Beirut, one of the few remaining landmarks of the civil war, which will soon open as a civic museum and cultural center dedicated to preserving the city’s memory and shifting identity. Until recently the house stood majestically, full of holes, astride the invisible “green line”—the partisan boundary that divided Beirut for so many years. The collection was found underneath the rubble of Photo Mario, a studio that used to be on the ground floor of the building now being renovated. Today the process of excavating images from the completely shrouded negatives can be seen as a metaphor for how the war is always latent, how it continues to shape the present.

Gelatin silver film negatives in a deteriorated state and digital positive images of those negatives, before and after cleaning treatment. Collection Beit Beirut.