Lawrence Abu Hamdan, The All-Hearing, video still, 2014. Courtesy the artist and Galeri NON.

Sultan Sooud Al Qassemi is a prolific art collector and sensitive political columnist, but he’s probably best known for bridging art and politics in 140 characters. During the heady days of the 2011 Arab uprisings, his Twitter account became a popular nexus of on-the-ground reports, documenting political developments as much as the culture of protest expressed in graffiti, slogans and songs. It remains an essential source for commentary about art and politics in the Middle East. Fittingly, Al Qassemi is, with Turi Munthe, co-directing this year’s Global Art Forum, which explores the theme of technologies and their impact on art and culture.

For nearly a decade, the Global Art Forum has served as a critical platform for interdisciplinary thinking in the Gulf, bringing together artists, writers and curators from across the Middle East and around the world. Titled “Download Update?” the ninth edition of the forum will feature talks by artists including Lawrence Abu Hamdan, James Bridle, Manal al Dowayan and the collective GCC together with leading figures at the intersection of technology and culture. The forum will launch in Kuwait on March 14 and continue at home in Dubai from March 18 to 20.

We spoke with Al Qassemi about the theme of this year’s Global Art Forum, as well as its cultural and political context, in the weeks leading up to Art Dubai.

Creative Time Reports (Marisa Mazria Katz, editor, and Kareem Estefan, associate editor): This year’s Global Art Forum is titled “Download Update?” Can you begin by telling us about the title and theme?

Sultan Al Qassemi: The idea is to discuss the role and impact of technology in the world of art and culture. We’ve invited a number of artists and academics to discuss the effects of technology not only on a global level but also on the regional level—specifically in the Gulf. There’s this impression that the Gulf, or the Middle East more broadly, is disconnected from the rest of the world. But a closer look makes it clear that some of the most connected youth in the world are based in Arab countries. Take Saudi Arabia—Riyadh is the tenth most Twitter-connected city in the world. Many Arab artists publish and sell their work using social media.

More generally, we have recently witnessed the globalization of Gulf culture. Many cities in the Gulf have become synonymous with world culture—especially Dubai, the home of the Global Art Forum, but also Doha, Abu Dhabi and Sharjah—and technology has played an important role in the globalization of this region.

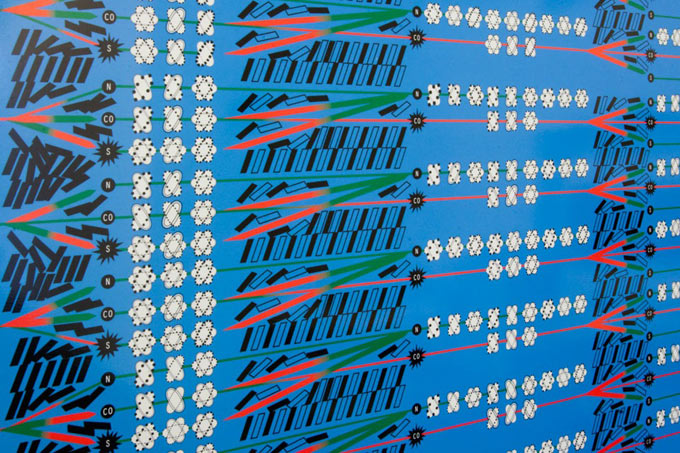

GCC, still from Ceremonial Achievements, 2013. Courtesy the artists and Kraupa-Tuskany Zeidler, Berlin.

CTR: It’s been four years since the more optimistic days of the Arab uprisings, when you became well known for translating and sharing on-the-ground reports through Twitter. What relationship do you see between new technologies and social movements? And how do you see art making political demands visible together with or in contrast to technology?

SAQ: I was active in documenting some of the popular chants that were used during the Arab Spring, but I credit technology with virtually extending that moment in early 2011. A lot of the art that was created during the uprising in Egypt was ephemeral; much of it was graffiti, and if it weren’t for technology, we would never have documented this art. A lot of graffiti artists would have their art painted over by the authorities within hours. But because of Twitter and Instagram, as soon as they finished their artwork, they’d take photographs of it, upload them to the internet and preserve the images forever. This art came to represent the culture and history of the country, whether in Egypt or elsewhere in the Arab world. We have seen a lot of art make use of technology to document slogans, chants and popular demands that some authorities would probably be happy to see forgotten.

Lara Baladi, Alone Together…In Media Res, 2012 (abridged one-channel version). Read about this video and Baladi’s archival work here.

Of course, political art thrived long before digital media, and it has always ranged from subtle critique to in-your-face advocacy. In some ways the genre of political art depends on the national or social context it’s addressing as much as the artist who is making it. In 1930s Egypt, there was the Art and Freedom group associated with the surrealists, who forged their own vision of liberty. A generation later Nasser mobilized art and culture for propaganda—to promote his pan-Arab narrative. Today, similarly, one sees propagandistic art in newspapers across the region.

CTR: Is there more pessimism about the relationship between technology and politics today than there was during the 2011 uprisings? Do you think activists still believe in the capacity of decentralized networks organized via social media to effect political change?

SAQ: There have certainly been shifts, not just from the early days of the Arab Spring but also from earlier moments in the history of media activism, as in 2006, when people in Lebanon shared the devastating effects of Israeli air strikes with the world. To speak to where we are today, I just published an article about social media in the era of ISIS. I don’t think people have lost faith in social media; however, the dynamic has shifted. Governments have introduced draconian restrictions on internet use, and a spectrum of extremists—from ISIS to conservative clerics—have increasingly taken to social media, which was until two years ago dominated by secular activists, as far as politics are concerned. Many left-leaning activists have either made their accounts private or turned to direct messages and private Facebook groups. However, this only emphasizes that they have not abandoned social media networks; they are just using them in different ways.

The “Friday of Victory” after Hosni Mubarak’s fall, Tahrir Square, Cairo, Egypt. Photo by Lara Baladi, February 18, 2011. Read Baladi’s essay “When Seeing Is Belonging: The Photography of Tahrir Square” here.

Of course, the internet will always have its good and bad sides. People around the world are understandably concerned about surveillance, for instance, but I don’t think the threat of being watched will turn anyone away from using the internet. It is a fact of life, a tool for communication, education and business that will not be abandoned, only used differently. Some people have become more attentive to what they share online; others still act as if their information is secure. But negotiating who we are and what we do online is now an accepted fact of life.

CTR: How do you think the ways in which people conceive of art—what they consider to be art or to be innovative in art—are changing as a result of their awareness of what new technologies can do to change, convey or document culture?

SAQ: I think there is more of an acceptance in the Gulf and in the Middle East of conceptual art. You see more performance art now. You see more video art now. You see more photography. You see 3-D printing. And you see hybrid practices, as in the work of Lawrence Abu Hamdan, who produces audio essays and installations concerned with freedom of speech, surveillance, borders and other human rights issues. Such practices were not around 10 years ago, or at least there were very few artists who were doing this kind of work.

Lawrence Abu Hamdan, Conflicted Phonemes, 2012. Installation view Casco Utrecht. Photo by Emilio Moreno. Courtesy the artist and Galeri NON.

CTR: Can you talk about the decision to have the Global Art Forum begin in Kuwait this year before it comes to Dubai? Kuwait was at one time a leader of the regional art scene, but attention shifted away from the country in the years after the Gulf War, and now there appears to be a resurgence of interest in Kuwaiti art and culture. What attracted you to bringing the Global Art Forum to Kuwait City before Dubai this year?

SAQ: Kuwait was the launchpad for the globalization of Gulf culture over half a century ago. Kuwait is where some of the earliest radio, cinema, theater and even political and social movements of the Gulf originated several decades ago. Kuwait was also the launchpad for the first Gulf publication in color that was sold not only in the streets and markets of the Gulf but also in Cairo, Damascus and Beirut. So for the first time, the Gulf had moved from being a receiver of culture—from the West, India and other parts of the Arab world—to being a broadcaster, a publisher, a producer of popular content. This is our way of tipping our hat to Kuwait and recognizing its pioneering role in the globalization of culture.

James Bridle, “Rainbow Plane,” installation, Pinchuk ArtCentre, Kiev, Ukraine, October 2014.

CTR: How does the Global Art Forum fit in with burgeoning cultural scenes in Sharjah, where you’re from, as well as in Dubai and Abu Dhabi?

SAQ: The Global Art Forum is an international forum, but we’re very keen on presenting some of the best practices from our hometown and from our region. And over the years it has encouraged artists to look beyond the local and formulate their thoughts, ideas and practices with a global audience in mind, especially since it coincides with Art Dubai and the Sharjah Biennial. This year the Global Art Forum will be hosting more artists and experts from the region than it has during any previous edition. We have invited local emerging artists, like the young collective GCC, as well as artists and thinkers who have been involved in the art scene for half a century. For example, Dr. Sulaiman Al-Askari, who was head of Kuwait’s National Council for Culture, Arts and Letters for several years, will discuss how the Gulf art scene has evolved over decades.