Left: Andres Serrano, Black Jesus, 1990. Right: Andres Serrano, Black Mary, 1990.

Even within the world’s strongest democracies, an artist’s free expression can be fraught with difficulty and danger, as the recent massacre by Islamist extremists at the satirical newspaper Charlie Hebdo in Paris has shown. I know something about those hazards firsthand. When I created the photograph Piss Christ, in 1987, I never thought that it would prove so controversial. I too was threatened, and the work was vandalized several times by those who considered it blasphemous.

Nearly 30 years later, in response to the Paris massacre, the Associated Press removed an image of Piss Christ from its editorial archives. We’ve seen the same impulse for self-censorship in the West before, as we see it in the refusal of many media outlets to publish the Charlie Hebdo cartoons at the heart of this recent tragedy. Given the seriousness of the violence, such self-censorship is understandable; it’s also a step backward at a time when we need to reassert the importance of free expression by artists, activists, journalists and editors alike.

For me, Piss Christ was always an act of devotion. I was born and raised a Catholic and have been a Christian all my life.

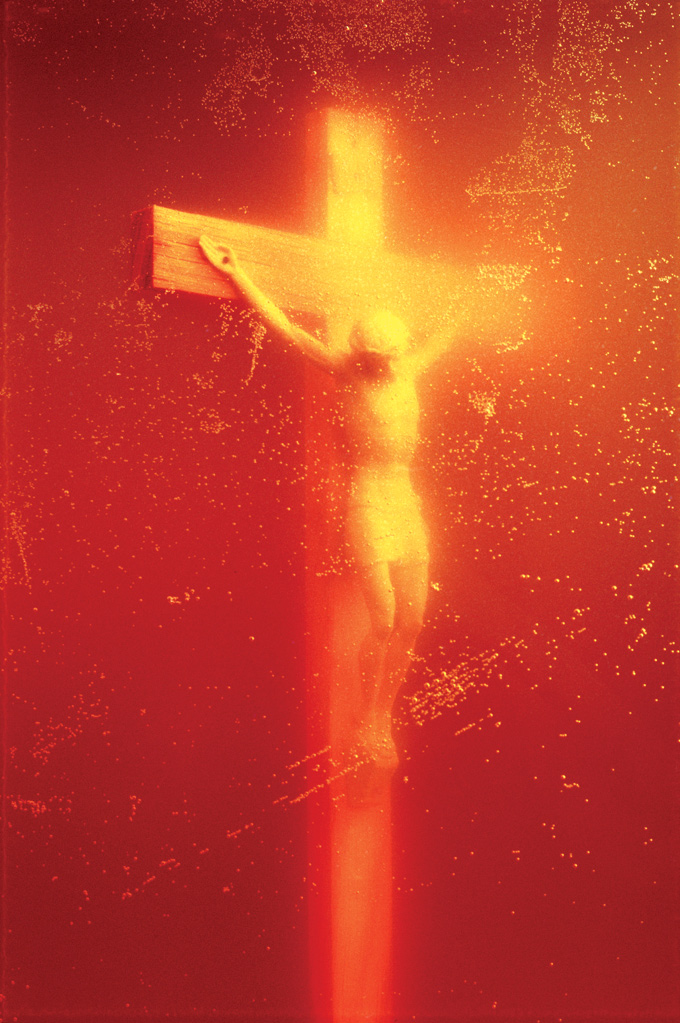

Piss Christ is a photograph of a plastic crucifix submerged in urine. (The crucifix was not “in a jar of urine,” as it has often been described, but in a large Plexiglas tank.) The photograph was part of a selection of works I submitted for a competition called Awards in the Visual Arts, organized by the Southeastern Center for Contemporary Art, based in Winston-Salem, NC. Ten artists from ten different parts of the country were selected for the award.

Award recipients were given a traveling exhibition and a $15,000 prize, which were funded by Equitable Life Assurance; the Rockefeller Foundation, a nonprofit philanthropy; and—most importantly in the context of what followed—the National Endowment for the Arts (NEA), a taxpayer-funded federal endowment.

Andres Serrano, Piss Christ, 1987.

The first stirrings of trouble came while the traveling exhibition was on display at the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, when a local newspaper published a letter from a reader complaining about Piss Christ. The letter caught the attention of Donald Wildmon, the head of the American Family Association (AFA), a right-wing fundamentalist Christian organization, which proceeded to mount a campaign against the photograph, petitioning Congress to denounce the NEA. Republican Senators Alphonse D’Amato and Jesse Helms picked up the gauntlet. They led the ensuing fight to try to defund the NEA—a seemingly perennial effort renewed by Capitol Hill Republicans since the Reagan years. It marked the beginning of what has since become known in the United States as the culture wars.

For me, Piss Christ was always a work of art and an act of devotion. I was born and raised a Catholic and have been a Christian all my life. As a child and especially as I was preparing for my Holy Communion and confirmation, I often heard the nuns speak reverentially of the “body and blood of Christ.” They also said that it was wrong to idolize representations of Christ since these were only representations and not holy objects themselves.

Freedom of expression comes at a price. It means putting up with people, ideas and arguments you don’t like.

My work was, in part, a comment on that paradox. I am neither a blasphemer nor “anti-Christian,” as some have called me, and I stand by my work as an artist and as a Christian. Where the photograph has ignited spirited debate, that has been a good thing. Perhaps it reminds some people to question what we unthinkingly fetishize (and thereby often minimize) in lieu of pondering seriously what the crucifix actually symbolizes: the unimaginably torturous death of Christ, the Son of God.

Unfortunately, times like these show us the true limits of people’s taste for debate, even in an ostensibly free society. Following the attacks in Paris, Bill Donohue of the Catholic League, like Wildmon of the AFA, used the tragedy as an opportunity to denounce speech he doesn’t like. In a statement, Donohue wrote, “Had [murdered Charlie Hebdo editor Stéphane Charbonnier] not been so narcissistic, he may still be alive.” Donohue appears not to see the irony of his statements: that he is failing to show the same “degree of restraint” he demands from artists and in ways that recklessly incite more violent hatred.

Left: Andres Serrano, The Church (Soeur Jeanne Myriam), 1991. Right: Andres Serrano, The Church (Soeur Yvette II), 1991.

Of course, the freedoms that protect Donohue are the same ones that protect artists; I wouldn’t want his rights denied any more than mine. But freedom of expression comes at a price. It means putting up with people, ideas and arguments you don’t like; it means defending those who agree with you and those who don’t, even when you find them offensive. We have only to look to our shared human history to find that the artists and thinkers who have most advanced civilization in the direction of freedom and equality were often unpopular in their day. They questioned, they analyzed, they regularly offended. Without them we would surely be lost.

Artists often work in mysterious ways, using unorthodox materials and ideas to challenge convention and put hard and necessary questions to powerful people and traditions. We don’t always want to hear what they have to say. But a free, tolerant society needs its artists and writers. And they must be free to live, work and speak without fear of censorship, attack or murder. Artists look ahead and plot the future. They map the culture and tell us where we stand. In doing so, artists are a free society’s greatest advocates and its best bulwarks. Their triumphs are civilization’s triumphs.

This piece, commissioned by Creative Time Reports, has also been published by Salon.