Mel Chin, Shape of a Lie, 2005, installation shot (recto/verso views). Bronze, Native American pipestone. Photo by John Lucas, courtesy the artist.

She kept pushing, bellowing, “I am VIP—I have the bands!” I twisted, as I couldn’t turn around in the crush with her clutch deep in my back, and saw her petite frame and fancy fashion backed up by her man, a six-foot-eight Nordic Lurch. This mimicry of a Walmart Black Friday line was happening at the most elite entrance to the elite Art Basel Miami Beach fair, reserved only for those with the fluorescent-green VIP bands coupled with special thin royal-purple wristbands, of which I had none. I pulled down my sleeve to conceal this fact and admonished, “Before you hurt someone, you should know that we all have bands and we are all VIP.”

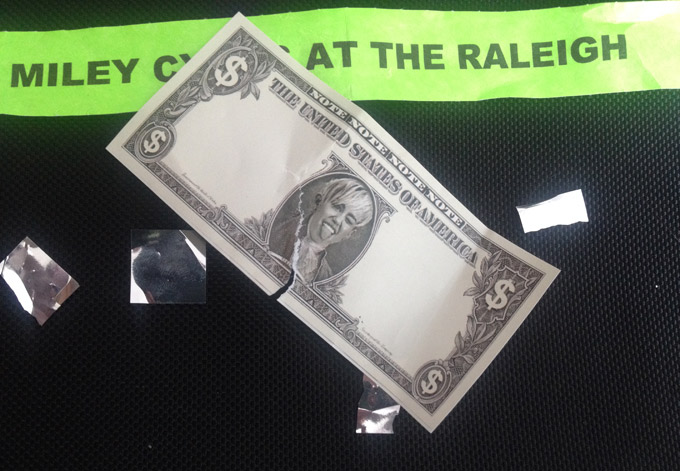

She backed up a bit, then the crowd surged again, and like a plump digested lump, I was excreted through the phalanx of band checkers. They noticed immediately, but before they could comment and send me to the iPad-equipped list checkers for official expulsion, I complained that the precious bands had been painfully ripped from my wrist while my cohort in this crash operation shouted, “Don’t you know who he is?” And within seconds, the lime-green “Miley Cyrus at the Raleigh” band was apologetically offered and affixed to my naked wrist.

Miley cash distributed at Art Basel – Miami Beach. Photo by Mel Chin, 2014.

Miley was already onstage and, with her Mylar mop-top and mirrored disco-ball pasties, seemed dressed in even less than wristbands as she rambled on about Miami permissiveness and who gave a fuck or shit about the shit she made. She covered “Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds” and “A Day in the Life” and performed a roots-revealing version of “A Boy Named Sue” with her signature energy augmented by a massive, energy-sapping LED backdrop.

I yearned for something improbable to emerge from Miley’s emotional channeling, something to challenge the entire light show of Basel

Dazzle

Admittedly I was surveying an art dealer–orchestrated spectacle through an occluded mindset. I was numbed by the news of the Eric Garner grand jury decision. At that moment I remembered the first brush my niece, a Hannah Montana fan, had with a non-post-racial America a few years ago, when she was confused by a slant-eyed gesture that Miley Cyrus made and later passed off as “goofy.” Those ignorant, racist ways effectively limited any celebrity attraction I might have had in Miami. But Miley was young then, and now her post-Disney white-trash persona—epitomized by tongue-out gesticulations that seemed oddly in line with my work Shape of a Lie and even more with the protruding tongue as a gesture of feminist defiance for Nancy Spero—was a possible sign of growth.

In between all this dark rumination, as Miley performed, there was a moment. She spoke with a blunt-induced raspiness that alluded to death and dark days and found a tremulous voice to convey a “dream you were dying / But I wasn’t even crying / I sang you to sleep . . . What does it mean? / What does it all mean?” I yearned for something improbable to emerge from her emotional channeling, something to challenge the entire light show of Basel Dazzle, a call to solidarity, a badass call to question what it means, this song about the death of a cat, the death of a dog, when a “black life does not matter.” But it didn’t happen.

Instead of asking, “What does it mean?” couldn’t we ask, “What can we do?”

Not a hater, I waited till near the end of her set, with my schmoozing dial turned way down. I moved toward the exit as hands were up in the crowd, not in “Hands Up, Don’t Shoot” gestures but to catch the last drizzle of Mylar diamonds and Miley cash being tossed to the crowd. On the street once more, I walked past the deco hotel entrances packed with limos, Maseratis and Teslas opposite piss-drenched storefronts. A black Bugatti raced me across the street as I walked the pedestrian crossing and won, hands down.

Why was I so bummed? What keeps Miley and me so goofy and incapable of responding to the crushing polarization of our country? Instead of asking, “What does it mean?” couldn’t we ask, “What can we do?”

Now, before I get so damn high and mighty, what’s up with me showing at this fair? Here I am, 63, in the middle of Miami “tryna get that rich,” I suppose. Hanging among peers nurtured to be rugged individuals with original, marketable talents. Guess I’ve been prancing puppet-like to art historical drummings, clinging to the tune that if your work has genuine critical weight then the awesomely attuned eyes of a refined collector and your savvy dealer will deliver the goods to support your rarified existence—and reward the best of our culture. Of course, the market trend has to be friendly, or you’ll molder for a hundred years in a pauper’s grave till your stuff is declared the dope and great hope of an auctioneer’s gavel. In the marketplace you can do no better than hear the pounding pronouncement of your worth, dead or alive.

Mel Chin at Miami Project. Photo by Edgar Arceneaux, 2014.

The Beatles’ Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band scored multiple Grammys in 1968, the same year that waves of rebellion hit the streets of Louisville, Chicago, Washington, Baltimore and Miami’s Liberty City after the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr. The 1968 riots were a reaction of despair to the murder of a man who had stood up and spoken out—together with Ella Baker, Bayard Rustin, Fannie Lou Hamer, Stokely Carmichael and so many others—against the unpunished murders of other black men, like Emmett Till. That history was tragically echoed in Miami with the riots that erupted in 1980 after another gavel’s acquittal of another African-American’s murderer(s): four police officers who suffered no consequences for the killing of Arthur McDuffie. That sorrowful cloud returned in Ferguson, MO, earlier this year, and it hung in the air in Miami, though it was a little hard to sniff out at the fair. With a little help from our friend, history, we learn to see the systemic racism that rears its head every day in the life of a black individual.

We can’t leave this (art) world in a spot where faux cigarette butts command top dollar and a single unsmoked “loosie” costs a black man his life.

It’s not just about race. Our deregulated capitalist economics, in which everything comes down to the bottom line, have dug a bottomless pit of disparity. If predatory profiling and ticketing the poor pay off, they will be done. These kinds of payoffs also instigate layoffs, as fleets of private jets take off, landing just in time for the VIP vernissage or the 11pm private poolside party. They arc over the pit and fly over an illusionistic bridge, forever promising equal opportunity and justice. On the ground and in the street, you can’t build or repair this bridge to span the pit if the foundations are strategically set against it.

Still, my expectations of Miley were too high. Before you can do anything, there should be an understanding of the obstacles. It will take more than renegade behavior or a provocative gesture to overcome the entrenched systems. Entertaining antics and creative expression are privileged in our perverse culture, which masks the hopelessness it creates and the brutality it pardons.

Ultimately I’m not interested in contemplating the dismemberment of marketplace Miami or in shaming anyone for enjoying Miley’s performance. I am interested in diverting some of the flow of my creative service into a collective imagination, joining others in a process of careful critique of the systemic racism that our era has inherited. From there we can devise methodologies to make meaningful contributions, alongside the marches, toward transformation. Revealing the hidden patterns that control mass sentiment and preserve injustice requires a brighter light and a legion of liberated, fearless tongues. Miley and I can contribute to the formation of an aesthetics of existence, so we don’t just leave this (art) world in a spot where faux cigarette butts command top dollar and a single unsmoked “loosie” costs a black man his life.