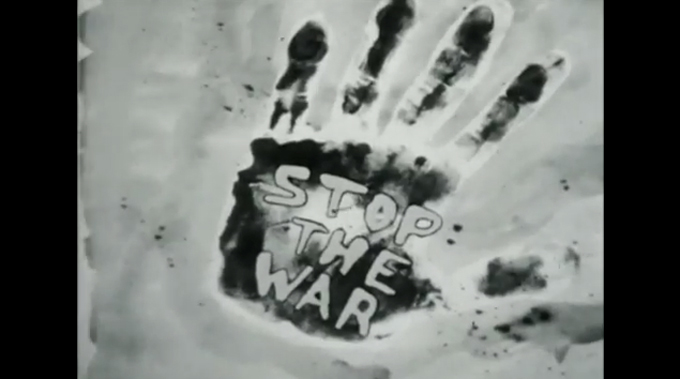

Still from Underground, directed by Emile de Antonio, Haskell Wexler and Mary Lampson, 1976.

When one of the world’s most courageous filmmakers hosts a screening of a documentary that she describes as “one of the most courageous films I know,” you buy a ticket. This November, as part of a curated series of films and events for Denmark’s CPH:DOX festival, Citizenfour director and The Intercept co-founder Laura Poitras presented the 1976 film Underground, an intimate portrait of the Weather Underground. Directed by Emile de Antonio, Mary Lampson and Haskell Wexler, Underground features rare interviews with members of the radical left-wing organization, interspersed with striking footage of anti-war and anti-racist demonstrations.

Talking with the Weather Underground was no easy task: at the time the group had lived in hiding for years, having declared war on the U.S. government and bombed the Pentagon, the Capitol and the Department of State in separate operations. But de Antonio, Lampson and Wexler gained the Weathermen’s trust and interviewed several of the collective’s members over three days in 1975. The resulting film is not only a remarkable account of an extraordinary moment in American history but also a beautiful and stirring documentary that stands out for both its ethical complexity and its stylistic innovation.

Observing so many parallels between the politics of the Vietnam War period and our own era of pervasive government surveillance, militarism and police violence, I reached out to one of Underground’s co-directors, Mary Lampson, to hear her thoughts on revisiting the landmark film today.

Still from Underground, directed by Emile de Antonio, Mary Lampson and Haskell Wexler, 1976.

MARISA MAZRIA KATZ: Do you think your perspective as a filmmaker brought something to the Weather Underground’s story that a journalist could not or that wasn’t being communicated in the mainstream press?

MARY LAMPSON: I think our intent was not just to report on them but also to offer them a platform to discuss who they were and what they believed. There’s a lot of tension in Underground because we were pushing them to talk about their own personal histories. As filmmakers we felt that was the best way to tell the story. I think that’s a side of the Weather Underground that you don’t really see in the news.

MMK: The dynamic between you and the Weathermen felt as though it was oscillating at times: there was trust in the beginning, and then we see it eroding. There’s one moment in particular when they become afraid and you console them. What did you do to make them feel safe and open up to you about their lives?

Many of the issues raised around American society still ring true— mass unemployment, growing inequality and police violence, to name a few.

ML: Actually I think it was more them making us feel safe, to tell you the truth. The trust was established as soon as my co-director Emile de Antonio proposed the project, because they knew his body of work. When he reached out to them, they recognized that he was a person they could enter this kind of conversation with. Beyond that, each one of us met with them in person, and when you have basic human interactions with someone, you establish that sort of trusting relationship. The risk to them was much greater than the risk to us was. So in fact they were the ones who created a safe place for the conversation to unfold.

Still from Underground, directed by Emile de Antonio, Mary Lampson and Haskell Wexler, 1976.

MMK: Since we are not permitted to look directly at the Weathermen but rather see your reflection while you interview them, you become a subject in the film (intentionally or not). Your face is so expressive. Were you conscious of your reactions while making the film, knowing that you would be someone whom the audience sees a lot of and perhaps someone with whom they identify?

ML: No, not at all. I felt a very intense connection with the Weather Underground because of the life experiences we shared, and the back-and-forth just came naturally. I’m a seat-of-the-pants kind of person. I go by my intuition on these things. I was attracted to the project because I had strong feelings about the subject matter. I had followed the Weather Underground and the protests against the Vietnam War very closely. I’m the same age as them, so it was my story as well—I did my research through life experience. I went into the interview with questions prepared, but what happened in that room was fairly spontaneous. Then the first time I screened the footage, I saw myself and thought, “Oh my God, how am I ever going to cut this film, having to look at myself all the time?” I just couldn’t … it was awful. But I got over it. After a while it didn’t even feel like it was me on the screen anymore. That’s what happens when you cut a film: the images take on a life of their own, and you become detached from them.

Still of archival footage from Underground, directed by Emile de Antonio, Mary Lampson and Haskell Wexler, 1976.

MMK: Watching Underground today, one can’t help but see that many of the issues raised around American society still ring true—mass unemployment, growing inequality and police violence, to name a few. What do you think about when you watch the film now? What do you think it can illuminate for audiences today?

ML: I think the film is more of an artifact, and I thought that at the time it was made too. For me, it has gotten better with time for this reason: it does a very good job of re-creating that moment in time and the complexity of what was going on. It’s a story that is not often told, which is important because history is often rewritten to exclude radical narratives like the Weather Underground’s (as Bill Ayers attests within the film). I think one of the great things about Underground is how, in a very direct way, it revisits that time.

MMK: Do you think a film like this would be able to be made today, in the hyper-surveilled world that we live in?

It’s a story that is not often told…history is often rewritten to exclude radical narratives.

ML: You know, I do. If Laura Poitras was able to make Citizenfour with that kind of access to Edward Snowden, I think it shows that you can still create a safe space where people feel comfortable to talk, even in this heightened era of surveillance. You have to be very careful when you make a film like this the way we did. There is a set of rules that must be followed: you don’t tell anybody you’re making the film, you take phone calls at pay phones and you know only what you need to know. (For example, we did not know who would show up for our three days of filming until they walked through the door.) Basically you need to keep your mouth shut. It takes a lot of discipline to do that, but yes, I think it is possible.

MMK: One of the most striking things about Underground is how it interweaves your footage of the Weather Underground with incredible images of what was happening at the time. How did you go about selecting those clips, and what were some of the stylistic choices behind those decisions?

Still from The Sixth Side of the Pentagon, directed by Chris Marker, 1967.

ML: Originally we were going to make the film secretly. If we had taken that path, we would have had a much more difficult time accessing all of that footage. When our project became public knowledge, that allowed us not only to access traditional news archives like ABC but also to reach out to other filmmakers who had made documentaries that touched on similar subjects. So there’s footage of the Pentagon from Chris Marker’s The Sixth Side of the Pentagon, images from Saul Landau’s Fidel! and scenes from Cinda Firestone’s documentary Attica. We were drawing from experimental filmmakers whom we knew and respected, and they were all incredibly generous when we asked if we could use excerpts from their films. I wanted to use that footage for aesthetic reasons because I didn’t want to treat the interstitial scenes like they were just “B-roll,” or neutral background shots edited to fit our words. So we went in the opposite direction and allowed the footage to speak for itself. We constructed the film around the tension between the existing images and the footage we shot with the Weather Underground. Then in the cutting room it all just came together.

MMK: It does add a lot of tension, but there’s some humor in there too. That’s an amazing feat because the war in Vietnam, for instance, or the conflict between an all-powerful FBI and a small group of radical activists would seem to be humorless subjects. The film is a mosaic, a rather untraditional way of looking at B-roll.

ML: Any great documentary doesn’t do B-roll. I almost refuse to use that term because it’s so against what actually making a film is. It’s such a TV journalism approach, in which you lay down the voice-over and cover it with “wallpaper”—that is, images. There’s no tension between the images themselves and the ideas expressed by the words. To me that tension is what makes a movie. It’s taking two things that don’t necessarily belong together and making something that does to elicit a response from the viewer.