Russian military officers collaborate with their American counterparts at a U.S. military facility in Colorado, Jan. 1, 2000. Screenshot of AP newsreel footage courtesy the artist.

On December 30, 1999, 20 Russian military officers began a unique mission in a strange land. For the next several weeks they would be stationed at Peterson Air Force Base, a U.S. military facility in Colorado, monitoring incoming data from satellites and radar systems around the world.

With their U.S. counterparts, and with interpreters, the Russian officers worked nonstop in eight-hour shifts in Building 1840—the ad hoc Center for Year 2000 Strategic Stability—to ensure the best possible flow of information between the United States and Russia while keeping a close eye on ballistic missile activity.

Decades of mistrust were set aside to reckon with the potential crisis of Y2K, a moment in time when computers might fail or behave unpredictably if they read the digits “00” as the year 1900, not 2000, on midnight of the new millennium.

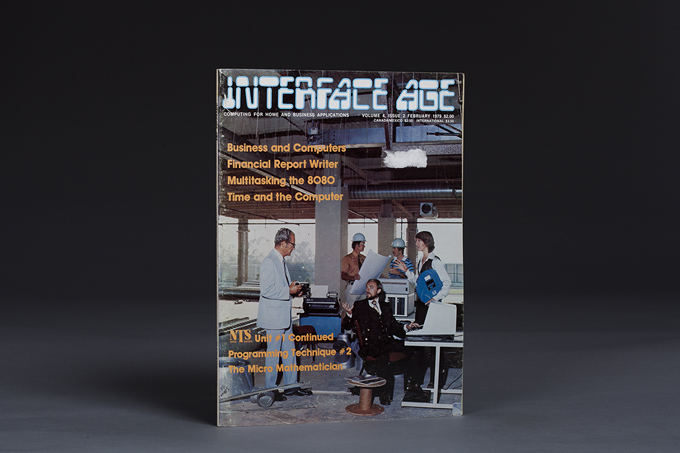

Perry Chen, Selection from Computers in Crisis, 2014. Photograph of journal included as part of the artist’s archive: Interface Age, February 1979. Courtesy the artist.

In a February 1979 issue of Interface Age, Bob Bemer, who is known as the father of ASCII (once the most common standard for encoding text characters in binary code), relayed a prophetic warning about the potential threat that would, decades later, become known as Y2K: “Don’t drop the first two digits for computer processing, unless you take extreme care, remembering that it’s only the ‘year of the century.’ Otherwise the program may fail from ambiguity in the year 2000.”

Bemer had long questioned the widespread use of two- rather than four-digit year dates in computer systems—a shortcut to save precious and expensive memory. In 1960, 40 years before Y2K, he campaigned for a universal switch to a four-digit year date standard.

As a practical matter, the only opinion that counted was that of the Department of Defense, the largest computer operator on earth. For bigger-bang-for-the-buck reasons, it was unshakable on the subject of year dates: no 19s. “They wouldn’t listen to anything else,” says Harry White, a D.O.D. computer-code specialist and Bemer ally. “They were more occupied with … Vietnam.”—Robert Anson, Vanity Fair, January 1999

Bemer didn’t give up his fight to sound the alarm about two-digit dates. Years later, according to Anson, he “recruited the presidential science advisor, Edward E. David, to plead the case in person. Nixon listened, then asked for help fixing his TV set.”

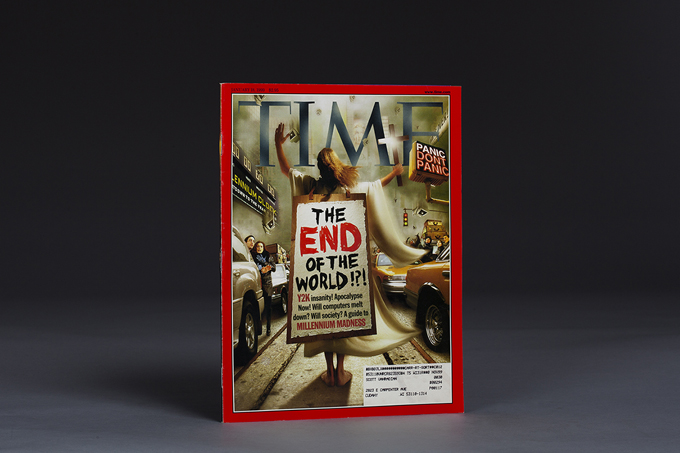

Perry Chen, Selection from Computers in Crisis, 2014. Photograph of magazine included as part of the artist’s archive: TIME, Jan. 18, 1999. Courtesy the artist.

By late 1998 the date issue was being taken very seriously, and Y2K concerns were at their height. Government and industry were spending at an increasing pace to avert failures in critical systems that could cause widespread and unpredictable problems. Many popular Y2K scenarios involved chain reactions of computer malfunctions that would cripple electrical grids and water supplies due to the vast and growing interconnectivity of many systems.

Mainstream media coverage abounded; a Y2K industry sprung up to service, explain and interpret Y2K for the public, and community leaders were forced into the role of educating people on how they should prepare for what Y2K might bring. The worry was loudest in the United States, where hundreds of billions of dollars were spent in preparation, but officials in other countries had their own deep concerns:

Paraguay’s Year 2000 coordinator said last summer the country would experience so many disruptions its government would have to impose martial law. Russia, Ukraine, Belarus and Moldova were seen as so risky that the State Department issued travel advisories and called nonessential personnel home.—Barnaby J. Feder, New York Times, Jan. 9, 2000

New Year celebrations in Auckland, New Zealand, the first major city to enter the new millennium without any Y2K-related crises unfolding. Screenshot of CNN footage courtesy the artist.

January 1, 2000, arrived first in the South Pacific, on the tiny Millennium Island, which had been renamed and realigned across the international date line to capitalize on the millennium hype.

Shortly thereafter, Auckland, New Zealand, became the first major city to pass the Y2K test. Thirteen hours later, Greenwich Mean Time, which many computer systems rely on, reached midnight without any major incidents reported.

At the U.S.-Russian Center for Year 2000 Strategic Stability … applause broke out as midnight arrived in Moscow. “You can see the lights are on in Moscow, and that Y2K is not a problem there,” said Col. Sergey Kaplin, the Russian military commander. … As the Russian and American commanders shook hands, Staff Sgt. Charles Dike lifted a toast of mineral water to the Russian officer sitting next to him. —Judith Graham, Chicago Tribune, Jan. 2, 2000.

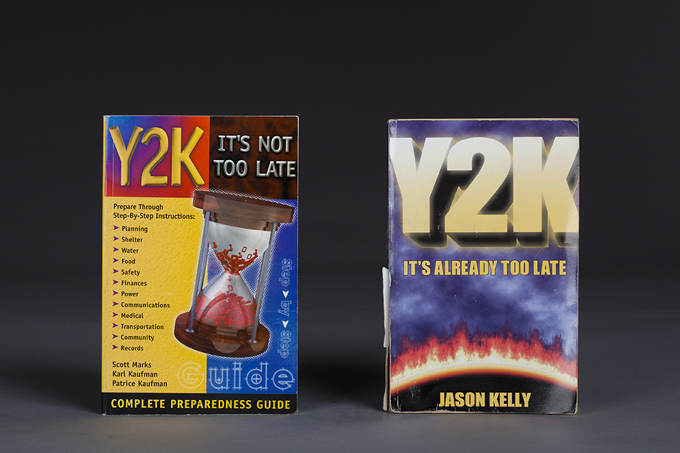

Perry Chen, Selection from Computers in Crisis, 2014. Photograph of books included as part of the artist’s archive: Y2K – It’s Not Too Late: Complete Preparedness Guide (Mercury: 1999) and Y2K – It’s Already Too Late (self-published, 1998). Courtesy the artist.

Was Y2K a crisis prevented or overblown? Why did countries that spent next to nothing on Y2K not experience any major issues? Could the uncertainty around Y2K have been approached in a radically different way?

Y2K did not lead to disaster. But it also did not lead to answers.

And until it became a punch line fading away in our memories, Y2K crystallized something bigger: that we were drifting into a new era in which our understanding of the complex systems we were creating was becoming truly limited, even as our dependence on them increased. And that we would need to learn to negotiate this new paradigm.

Technology has become so complicated that we no longer understand it. Most people have suspected this for a while, but now they know for sure that there is not somebody somewhere who understands how it all works. Of course, those of us close to technology have been certain of this uncertainty for a long time. —Danny Hillis, Newsweek, May 1999

Hillis was no Y2K doomsayer. In fact, these thoughts come from an essay titled “Why Do We Buy the Myth of Y2K?” Hillis, an inventor and scientist who pioneered the concept of parallel computing, was looking beyond Y2K:

I have come to believe that the Y2K apocalypse is a myth. The truth is not that civilization will come to an end, but rather that civilization as we once knew it has ended already. We are no longer in complete command of our creations. We are back in the jungle, only this time it is a jungle of our own creation. The technological environment we live within is something to be manipulated and influenced, but never again something to control. There are no real experts, only people who understand their own little pieces of the puzzle. The big picture is a mystery to us, and the big news is that nobody knows.

This piece, commissioned by Creative Time Reports, has also been published by Rhizome. For more of Chen’s work on the topic of Y2K, see the online exhibition “Computers in Crisis” and the upcoming event Y2K+15, Friday, Dec. 12 at the New Museum in New York.