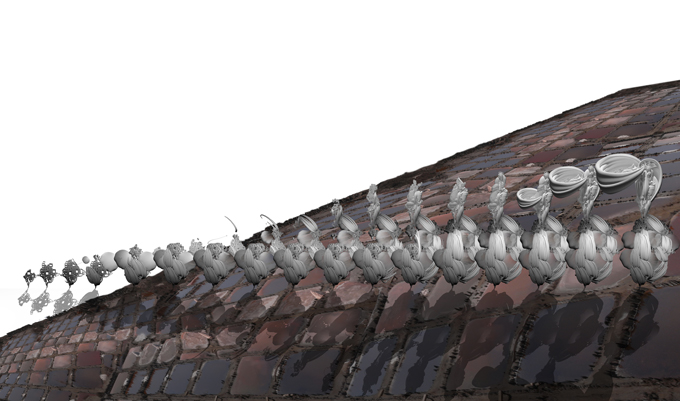

Alexandra Pirici, If You Don’t Want Us, We Want You, 2011. An intervention in public space in Bucharest, which was followed with interventions around the monuments of Peter the Great, Catherine the Great and the Lenin Statue at the Finland Station for Soft Power – Sculptural Additions to Petersburg Monuments, 2014. Photo courtesy the artist.

Nato Thompson: What are your thoughts about the recent European parliamentary elections, particularly the rise of right-wing nationalist parties and people’s sentiments toward immigration?

Saskia Sassen: First, I don’t think we can put the blame for these right-wing politics on the people who voted for the right-wing politicians, because their actions are only symptoms of a much larger, more destructive dynamic fueled by those with power depriving more and more people of real opportunities. People are crawling into what was once a prosperous middle-class situation only to find that the stable livelihoods that they expected for themselves or their children have disappeared. The third and fourth generations after World War II are not getting anywhere near where they or their parents expected to get. From the extraordinary downward push of wages to the elimination of choices and the weakening of citizens’ rights, a vast assemblage of negative forces has pushed people against the wall.

Art can be very important: you can suggest other worlds, through other ways of seeing and narrating the world in which we live.

A second factor contributing to Europe’s rightward shift is that there is no political speech, no voice, that can move public discourse into some alternative zone of narrating the current condition, so people fall back on familiar, elementary nationalisms. This is where I think that art can be very important: you can suggest other worlds, through other ways of seeing and narrating the world in which we live. The average voter—who does not have a lot of power, who is losing resources, whose children are not doing very well—confronts a lack of choices when it comes to apparently simple questions like “How do we speak about this crisis?” “How do we explain it to ourselves?” “How do we explain it to our children?” And so out come these absolutely, horribly regressive statements.

Europe has always had various forms of racism, as I attempted to show in a book I wrote about the history of migrations, Guests and Aliens, which focused on Europe in the last 200 years. Take what happened when Haussmann, as he prepared to rebuild Paris, recognized that he needed more workers. Since France is predominantly Catholic, he brought in Catholic workers from Belgium and Germany. They were immediately attacked by French workers for being the wrong kind of Catholics. Coming back to today’s situation, when you feel exploited or when you feel your unions are getting devastated, there is going to be a reductionist construction, a scapegoating, of whoever is seen as the cause of these conditions. Racism is part of Europe’s history, profoundly so, but there has been a surge in the right wing—even in a murderous right wing—whose actions resemble those of terrorized people. I think that the disaster of economic loss—the impoverishment of the middle classes—and the lack of politicians who can really articulate an alternative are partly responsible for this movement.

NT: What forces would you say are responsible for this erosion of possibilities, these diminishing horizons, for the working class?

SS: The political logics at work in today’s economy are not, in my view, adequately captured by the discussion about inequality. Inequality has always been with us; inequality is a distributional question. I want to situate that distributional process, which inheres to all complex social forms, within a larger, systemic framework. I find that language like “growing inequality” or “rising poverty” ceases to be helpful at some point. For my latest book, I came up with the term “expulsions,” which I distinguish from the far more familiar “social exclusions,” in the sense that social exclusion happens inside a system. It’s an internal distortion. When I talk about expulsions, I argue that we’re seeing a multiplication of systemic edges in our society—edges of economic systems, political systems or simply “the system,” so to speak. Once you’ve reached that systemic edge, you’re dealing with an extreme condition, and in that sense an edge makes something visible. But at the same time, when you cross that systemic edge, you are expelled from the system completely, and you become invisible.

Finance is not about money, unlike the traditional bank. The traditional bank sells what it has: money. Finance sells something it does not have.

When the very long-term unemployed are no longer counted in the unemployment rate, they cease being, statistically speaking. They are material beings—you can see the bodies—but they are literally made invisible according to the standard statistics we use to explain what is happening in the economy. I argue that this expulsion has the effect of an economic cleansing. It allows the U.S. government, the Greek government, the Spanish government, whatever, to say, “We’re back on track; we have a little bit of growth now.” But it’s because they have eliminated all kinds of workers who would drag down the positive indicators. When a small farmer in India or a small shopkeeper in Greece commits suicide because s/he can’t sustain his or her business, which is happening more and more often, if that person does not declare bankruptcy before s/he commits suicide, it doesn’t get counted in the economy. It’s an invisible event. The challenge, then, becomes to understand what all is expelled from our standard economic measures.

We are living in a brutal period, partly because we have reached these extreme conditions but also because once those extreme conditions are in place, whatever crosses that edge becomes invisible. Rendering such conditions or trends invisible allows our leaders to speak of progress and stability. To me, this mix of negative developments is a defining feature of our time. It’s the opposite of the post–World War II era of mass manufacturing, with its boom in the construction of suburbs and highways—projects that expanded the demand for workers. Back then, the workers were also the consumers, a situation that produced incentives to pay a decent wage. That was a dynamic that in effect expanded the space of the economy, even taking into account the racism and exclusions that happened during that period. Today the dynamic is geared toward shrinking the space of the economy and pretending that all the people who have fallen out don’t exist.

Cover photo for Saskia Sassen, Expulsions: Brutality and Complexity in the Global Economy, 2014.

NT: The full title of your new book is Expulsions: Brutality and Complexity in the Global Economy. I want to talk about the word “complexity” because in my own political experience I find that I never trust it. For example, when you start talking about accountability or responsibility, often people will say, “Yeah, yeah, maybe they’re to blame, but at the same time it’s really complicated,” or “Obama’s really trying his best, but the political system today is very complex.”

SS: [Laughing.] It’s complicated…

NT: What I’m trying to understand is, what are the political uses of complexity? How do we approach complexity in a way that gives us agency?

SS: Those are two big, and different, questions. My interest is precisely in taking complexity down and saying, “These may be very complex systems, but too often they produce very simple, brutal situations.”

NT: Right.

SS: In fact, each of the chapters of Expulsions plays on that dichotomy between formal complexity and brutal simplicity. For instance, I have a chapter on finance, in which I argue that if you want to understand finance do not ask the financier—because he’s going to give you a language that is indeed complex and you won’t understand a word. Give me 20 minutes, and I’ll explain finance to you—in fact, I’ll do it here in one minute! Finance is not about money, unlike the traditional bank. The traditional bank sells what it has: money. Finance sells something it does not have. And in that selling of what it does not have lies its creativity: it has to invent instruments. Ultimately finance is only an array of instruments; it doesn’t produce anything. For high-finance firms to make a profit, they need to speculate on the products of other sectors. These firms have developed tools that allow them to invade very fancy sectors and extract their goods to create financialized commodities and financialized real estate and so on. Eventually they financialize everything—used cars loans, student loans, subprime mortgages and so on. Finance, by design, must invade other economic sectors because the latter provide the grist for its mill, so to speak. Once you recognize this, you begin to see the dangers of finance capitalism. You begin to understand that it uses incredibly complex forms of knowledge to engage in rather elementary extractions of profit. Our present economies employ brilliant minds, for whom this is all a technical problem in which the sole concern is functionality. But in fact they produce these complex instruments that maximize profit, and they do not look at the consequences for other, more vulnerable sectors.

NT: So how do we make a complex system accountable so that citizens can have some sense of agency?

SS: A lot of issues are presented as complex, and we need to simplify them to understand what they are really about. One shouldn’t try to understand an issue in the language that the sector uses, whether that is advanced mining or finance or contract law; rather, one has to stand back and ask, “OK, what are they really doing?” For instance, with fracking, you know what they’re doing? They’re destroying stuff. [Laughing.] They’re drilling into the earth and bombing rock formations to release gas. As for banks, they pushed mortgage contracts onto modest-income people so they could use the material asset, mix it with high-grade debt and then sell the resulting financial instrument as an asset-backed security. This is what the high-level investors were after—enough derivatives and interest rates, they thought, give me an asset-backed security.

Steve Lambert’s Capitalism Works for Me! (True/False) in Times Square. Photo by Jake Schlichting for Times Square Arts, 2013.

NT: Thinking about those living at the extreme edges of society, where the brutality of the system is manifested, I would like to consider how those in power exploit generalizations about these populations. To return to what we talked about at the beginning of our discussion, why does racism work so well in the political sphere? This isn’t new—it’s been effective for a very long time—so what is it about the political sphere that allows these edges to be so easily co-opted to produce racist ideologies?

SS: Very good question. First, let me clarify: one of my arguments is that we have always had these expulsions. But I argue that today those edges are closing in. They are advancing into the lower and middle classes, shrinking the economic space and leaving out more and more people. On the question of racism, I am interested in Europe because many of its countries are culturally similar. Large stretches of Europe were once part of a single empire that shared language and history. So I like to use Europe as a way of exploring the following question: when the outsider—the arriving immigrant—is your cousin, is s/he treated differently by the receiving community than today’s immigrants who come from non-European areas of the world? And the answer is no.

There is always an

object for racism, though that object can easily shift…no matter whom racism is

directed against, there is always a little cubicle ready to house it.

In Europe the object of racism is the outsider, whose history is different from that of immigrants to the United States. European racism plays on a strong vector of insider or outsider. Europe is a small continent, in which even small towns functioned as cities in earlier periods, and cities were made up of a collection of residences and individuals integrated into the social fabric. Cities had good records of their populations because the European city was a collective project: all citizens knew who had recently arrived and whose family had lived in the area for generations. So that meant that making someone an insider was a big deal. It’s very different from the situation with a frontier settlement like the United States or the economic centers of Asia, where there is no anchored population. When you arrived in a European country, even if you look the same and share the same religion as most of the population, that’s not the issue. The issue was that you had to be incorporated fully—and that still holds true in many areas in Europe.

In the United States, communities have shorter histories, and they are more fluid—the mindset is, “You want to come, you come, but you are on your own.” The racism emerges at the level of competition for jobs and resources; it’s a different type of fear of the outsider, which depends on the economic situation. Today it is particularly bad, as most modest-income workers feel threatened—not only in the United States but also in Europe, given its presently high unemployment and impoverishment.

I do think it matters how you understand racism. I think it is made; I don’t want—I refuse—to accept the notion that we humans are inherently racist. I refuse that. We make it. Why, in all societies that I know, is this fear of the “other” always there? I don’t know, but we construct it through complex intermediations in which we lose sight of the extent to which it is made. And there must be some element to racism besides its being made through particular intermediations; there is also an element of existential fear, a fear of the other, which is far broader than racism—it manifests in the gender divide as well. The task is not only to acknowledge the contents of these racisms but also to understand how we make them.

Community organizations at the “Beyond the Block” party in Sunset Park, Brooklyn, 2012. Photo by Sound Liberation Front, featured in Jace Clayton’s “Transnational Sounds, Local Struggles: A Brooklyn Rent Strike Mix from DJ/rupture.”

Now in Europe it has taken on a whole other dimension because today’s outsider may adhere to another religion, notably Islam. That is why I like to remind people that when the outsiders were Catholics, your “cousins,” you killed them too. I think that today the virulence of the anti-black, anti-immigrant sentiment is a symptom of a social system that is no longer functioning. It’s become a very harsh system where the edges are hard: when you’re out, you’re out, and you’re losing ground fast. To all of this we should add the fact that many immigrants today are being expelled by the massive landgrabs in the Global South.

NT: In relation to our discussion around complexity, it strikes me that racism simplifies things very clearly for people. However, it seems that racism is not only about who you are or who you aren’t but also about how you fit into a system of power.

SS: Exactly. Racism is something that fulfills a systemic function. It may take on different contents, there may be different logics at play, but essentially it is part of how we construct a system. There is always an object for racism, though that object can easily shift. We’re totally comfortable with incredible contradictions; no matter whom racism is directed against, there is always a little cubicle ready to house it. This is one of the serious imperfections of the systems that we have constructed. Class is a kind of racism too, mind you.

NT: For this year’s Creative Time Summit we’ll go to Stockholm. Scandinavia’s often thought of as a region with strong social welfare states that have historically been fairly homogeneous. Currently the Swedish government is rethinking its social welfare policies as it encounters the complexities of immigration. So these issues of “insider” and “outsider” are certainly at the forefront in Scandinavia, as they are in much of Europe. Thinking about how immigration plays into these political narratives, who’s using it to their advantage and for what?

SS: For many politicians, immigration offers an accessible explanation that gets them off the hook: “Here are these outsiders taking away your jobs.” There’s also the fury of impotence: you know you’re qualified, but you can’t get a job; you see your household falling deeper into debt, and you risk losing your home. Can you imagine the traumatic trajectories that people are experiencing? And indeed it’s very difficult to feel the same passion about the financial system that one might feel about immigrants. Poverty produces deep pain, but it also produces passion and hatred, and you have the immigrant, the “other,” to be its object.

NT: In our summit we’re focusing on the ascendancy of right-wing governments across Europe and the historical and geopolitical conditions that are bringing them into power. Do you see any conditions globally that might produce counternarratives or other ways to deal with austerity measures and immigration issues?

SS: In response to the first part of your question, racism is an easy way out for those who don’t make an effort to understand the factors that are contributing to this rightward shift, such as growing inequality, capture at the top and so forth. We’re dealing with a complex and elusive system of power. Far more visible than the culprits are the immigrants, the Muslim citizens, a situation that leads to a fear of people rather than of predatory systems. A politics of misplaced fear.

This is a predatory system that we cannot fully control. We have to destroy it, and that’s going to take an enormous amount of courage and knowledge on the part of those who resolve to disrupt it. We are way beyond predatory elites, which have existed for most of human time. Today one of the major challenges we face are what I would call “predatory formations.” These include elites but also technical capacities, legal instruments and engineering modes that all get geared toward exploiting people and the biosphere—that is, toward satisfying the greed of powerful capitalists. Digital financial networks are open networks, and they’re composed of algorithms that are open constructions. We cannot fully control them—that’s why every now and then financial firms do go broke, though of course they gain it all back in one way or another (lately by grabbing citizens’ money through bailouts). There are also certain laws and statutes that facilitate this predatory behavior; I am of the mind that we ought to throw out a lot of laws and make some new ones.

NT: I couldn’t agree with you more.

SS: We have these logics and systems that are not really working. Look at the United States: it can produce more and more military might, but to what end? There is a whole production and financing chain set up to produce the most advanced bomb, but we cannot get to the 6,000 bridges that are inevitably going to fall down sooner or later. What is happening in a system that has become so complex that parts of it have dropped out unnoticed? I think that this is a period in which we are witnessing the decay of the liberal state. The liberal state has always been a class state, but it was a state of the middle class, and it worked all right. Now it simply doesn’t have a middle class. The middle class has been mostly destroyed. I don’t know what comes next.

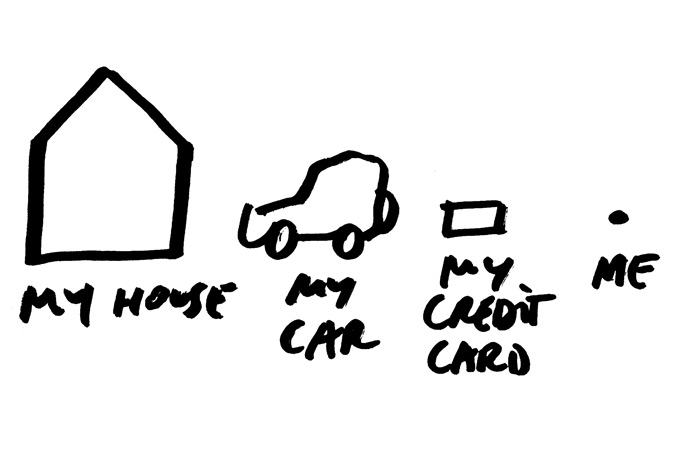

Drawing by Dan Perjovschi, 2003.

NT: Right now it seems that there are a few major issues looming over the political conversation. For example, climate change: here you’ve got something that everyone can agree poses a threat; it’s not even debated anymore. The world agrees, yet nothing happens, and you begin to realize that our political system has no capacity to stop it.

SS: The internationally adopted policy of carbon emissions trading—or cap and trade, as it’s often called in the United States—is frankly a joke. It’s redistributing the right to damage. Emissions trading is basically a negotiation for the right to pollute a bit more—and a game to keep government officials busy and talking about the environment.

I called the environment chapter in my book “Dead Land, Dead Water,” and I had forgotten about this: the other day somebody sent me an email suggesting that instead of “climate change,” we should be using a more ominous phrase like “dead land” to get at the reality on the ground. “Climate change” is noncommittal; it signals a shift but not necessarily a bad one. I tend not to use the phrase because it’s a bit too abstract; it implies that climate change is out there and natural somehow. I say we killed land. We are killing land. We are killing water. I notice then that people really begin to understand what I’m actually saying. Climate change: the words are beautiful, elegant, encompassing, but words are living animals, and these two stopped delivering the goods at some point.

NT: “Dead land,” I like that. That works. [Laughing.]

SS: It’s a bit dramatic, but I don’t think of it as replacing the words “climate change” entirely; it’s just a more vivid way to describe what’s happening.

NT: This summit brings together artists from around the world. One of the presenting artists, Tania Bruguera, started a project called Immigrant Movement International, which attempts to shift how we think about immigrants. It’s a good example of a project that tries to reimagine what the political is or where the appropriate political sphere is for art, positing that art can in fact produce a new reality. Art can be a place for the production of the political in the public sphere, when venues thought of as “political” are losing their capacity to accomplish anything political. Could you speak to art’s potential to produce political space?

A children’s art class at Tania Bruguera’s Immigrant Movement International, 2011.

SS: Art can indeed make—a space, the political. I want to emphasize the importance of capturing the making of something. We make inequality. We make justice. We make poverty. It doesn’t just fall from the sky. What are the spaces where those without power, the powerless, can actually make presence, make a history, make a politics, even if they do not result in empowerment? Because this is a real thing in the Anglo-American imagination—if you are powerless, you can rescue yourself from the forces of power only if you yourself become empowered.

I think empowerment is pretty tricky. It’s a beautiful word, but it’s not easily attained. I’m interested in this zone between powerlessness and empowerment. I think this is where much of the making of history by the powerless plays out. It is where one can exit a condition of elementary powerlessness and enter an ambiguous zone where you get to be a maker, even if you don’t become empowered. I argue that the city—unlike suburbs, unlike office parks, unlike endless housing complexes—the city, with its slightly anarchic elements, with its crowds, is actually one of the spaces where those without power have agency, because it’s not a fully controlled space.

The street is an

indeterminate space where the powerless can be makers.

I am very interested in how the recent occupation movements happened. The piazza is a ritualized public space, with embedded notions of how you are supposed to conduct yourself. The street is an indeterminate public space; you don’t even think of it as a public space. And by street I don’t just mean a street—it could be an empty plot of land because a building is being destroyed. I’m interested in the notion that occupation movements are not necessarily the same as an “Occupy” movement. Occupation movements include squatting in abandoned or threatened buildings or gathering in public space, whether one uses the word “Occupy” or not. There are such movements happening all over the world now.

The “Friday of Victory” after Hosni Mubarak’s fall, Tahrir Square, Cairo, Egypt. Photo by Lara Baladi, February 18, 2011.

It’s a natural impulse to occupy. It’s a way of making territory, and territory is not land, it’s not space, it’s not ground, it’s not terrain. I think of territory as a complex mix of material and immaterial elements. The material logic of possessing citizenship, which for modern Western democracies is the pinnacle of selfhood, collides with the abstract logics of power—the state and its project to control territory, sometimes even another country’s territory. I began to think about loosening up territory, analytically speaking, so that it can be used for other purposes. The street, as I said, is an indeterminate space where the powerless can be makers. When you build a mega complex that takes over the streets of a neighborhood and leads to the privatization of everything, you lose indeterminacy. It may be an architecturally complex building, but it reduces the complexity of urban space.

NT: Increasingly, many of the artists we work with are interested in producing spaces of civic or social potentiality. I think it’s such an interesting time for art’s relationship to political theory in that there’s a form of thinking that is grounded in the world—thinking as doing, thinking as making countersystems—but how do we produce under this condition of predatory formations?

SS: We must reject certain supposedly natural laws that they’re selling us: “we need to rescue the big banks to rescue the country,” or “if we do A, then B will come and then C, and you will be happy.” We must make spaces—economic, social and cultural spaces. I’m often asked, “What do we do?” and I say we begin by relocalizing the production of as many necessities as we can—from urban agriculture and carpentering to art and culture. This is something that comes more easily to neighborhoods and small towns. It’s not going to work the same way in downtown Manhattan, but you begin to work, and you begin to make alternative space. It is of absolutely critical importance that we return to credit unions and small local banks so that the consumption capacity, in this case in the form of the interest you pay on a loan, recirculates locally in the form of what residents of a community buy and sell. This is one thing that high finance has destroyed—it has killed about 10,000 small local banks and credit unions since the 1980s (PDF). We keep allowing the expansion of major firms through their franchises: this means that part of a local community’s consumption capacity actually leaves the community, and there is no growth. The same thing can be said about loans and the interest payments people and firms in a community pay to big international banks, such as Citibank in the case of the United States. We inevitably get poorer and poorer. So I must emphasize the importance of making it our economy, bringing the economy down into your neighborhood, whatever part of it you can. There is no reason for most consumer banking to be in the hands of the five biggest banks in the country.

We have become too dependent. At this point we depend on very complex systems to produce certain things, and we always will to some extent, but we could do more by ourselves in our communities. It’s a step in a trajectory toward becoming a maker, in which you make politics and you make culture, and you make some of your food and some of your furniture and so on. By being makers, we resist flattening ourselves into being consumers. A similar argument applies to how we can combat environmental destruction. We must work with the biosphere and use her capacities far more often than we currently do. We should be working with bacteria and algae and mushrooms to replace all kinds of chemicals.

NT: Saskia Sassen, you are the raddest because I agree with you 100 percent.

SS: [Laughing.]

NT: I think that analysis in and of itself speaks to the hearts of a lot of artists who feel that sometimes they don’t know how to deal with all of these international forces. It’s more tangible to think, “I can work in my neighborhood with people I know and build a community with people I don’t know.”

SS: Exactly! I want to—I must—believe that certain crises should be an opportunity. We need to find logics that allow even negative conditions to become sources of strength, in which we turn into makers as a community. These communities can be electronic and multisite—they’re not limited to the physical neighborhood—but they hinge on a notion of collectively making what is most important to us.