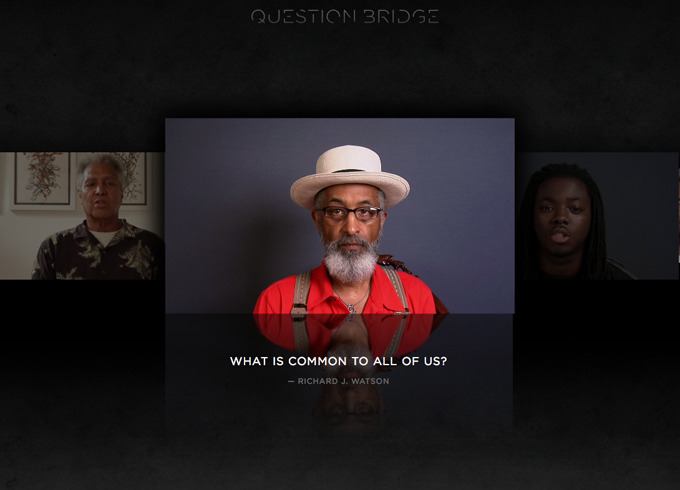

Screenshot from “Question Bridge: Black Males,” a collaborative transmedia project of Chris Johnson, Hank Willis Thomas, Bayeté Ross Smith and Kamal Sinclair. Produced by Jesse Williams, Deborah Willis and Delroy Lindo.

Every person has a “day of infamy” in his or her life. For the parents of Jordan Davis, that day was November 23, 2012. For the parents of Trayvon Martin, it was February 26, 2012. For the parents of Michael Brown, it was August 9, 2014. For me, it was February 2, 2000—a Tuesday. That was the day I lost Songha Thomas Willis, my cousin, roommate, best friend and, for all intents and purposes, big brother. He was shot dead in front of dozens of people during a robbery in which he did not resist.

One of the most chilling aspects of Songha’s murder was how strangers sometimes suggested that he might have been involved in an activity or community that had put his life at risk. “What did he do? Was he…?” The presumption is that, by virtue of his being a young black male, he held responsibility for his own untimely death. The day Songha died was a day of horror, but it was also a day of redefinition. In the nearly 15 years since, I have struggled to find creative ways to deal with my cousin’s murder and the criminalization and genocide of African American men—if not to find answers, then, at least, to ask better questions.

Black men are too often seen as a homogeneous group. Nothing could be further from the truth, or more damaging. Misguided perceptions increase the likelihood of aggression toward black men and affect the way their lives are valued in our schools, on our streets and throughout our criminal justice system. In many of the cases above, young men were seen as a threat by their very existence alone, a perception that justifies violent action against them as “self-defense.”

This summer has been one of the most notorious periods of public violence against African American men in decades. And to top it off, this week will see the retrial of Michael Dunn for the 2012 murder of Jordan Davis, a 17-year-old boy who was killed for playing rap music too loud. Earlier this year, a Florida jury in the so-called “Loud Music” trial convicted Dunn on one count of firing into a vehicle and three counts of attempted second-degree murder for firing at the three other unarmed African American teenagers who were in the vehicle. Unconscionably, the jury could not come to a conclusion on the first-degree murder charge in relation to Davis. Dunn, who is white, claimed that he was acting in self-defense under the state’s now infamous stand-your-ground law, though he stepped out of his car to assume a shooting position and fired at the teenagers even as they drove away.

Surprisingly, the issue of race was rarely addressed in the trial, even though Dunn referred to the music played by the boys as “thug” and “rap crap,” coded ways of saying “nigger” and “black music.” In documented correspondence, Dunn stated, “I’m not really prejudiced against race, but I have no use for certain cultures. This gangster-rap, ghetto-talking thug ‘culture’ that certain segments of society flock to is intolerable.” He continued, “This may sound a bit radical, but if more people would arm themselves and kill these (expletive) idiots when they’re threatening you, eventually they may take the hint and change their behavior.”

Jordan Davis’s parents said that their son was a lover of country music too, and suggested that perhaps, had he been blasting that genre of music instead of hip-hop, he might still be alive. This may or may not be true, but there is an important message in this suggestion. Davis was a multifaceted human being, but he was not perceived as such, nor was he allowed to inhabit the full complexity of his humanity.

Chris Johnson, Hank Willis Thomas, Bayeté Ross Smith and Kamal Sinclair, Intro: What Is the Last Word We Can Remember You By?, from “Question Bridge: Black Males,” 2012. Produced by Jesse Williams, Deborah Willis and Delroy Lindo.

This is the impetus behind “Question Bridge: Black Males,” a collaborative transmedia art and social science project where the researchers and the subjects are also the control group. The project’s aim is to represent and redefine black male identity by facilitating candid conversations among hundreds of self-identified “black men.” Its formal structure is deceptively simple: participants are invited to video-record a question for other black men. Black men who feel equipped to answer are invited to record a response.

“Question Bridge” was created by Chris Johnson, myself, Bayeté Ross Smith and Kamal Sinclair, but the list of collaborators grows with each new voice. The most astounding aspect of the endeavor has been the myriad questions asked and the dramatically different answers given in response to a single question. This serves to emphasize the diversity of perspectives of men who live within the expanding rainbow of blackness. By isolating this group along institutionally prescribed demographics and asking them to ask and answer each other’s questions, it becomes evident that there is as much diversity within any given demographic as there is outside of it. This inevitably blurs the lines of blackness to the degree that it becomes a gray area that is harder to police, imprison and profile.

Chris Johnson, Hank Willis Thomas, Bayeté Ross Smith and Kamal Sinclair, Blueprint, from “Question Bridge: Black Males,” 2012. Produced by Jesse Williams, Deborah Willis and Delroy Lindo.

To this end, we recently launched a user-generated platform called “Question Bridge Interactive” as an invitation for self-identified “black men” to speak, and to be seen and heard in all of their complexities and contradictions so that they can no longer be pigeonholed, marginalized and dismissed as a group. As the questions and answers grow, so do the opportunities for deep listening, self-expression and freedom. Each man who creates a profile is asked to create multiple identity tags to encourage self-defined, multifaceted identity models. These tags attach each man to a new community of people, made up of those who see themselves in similar ways, demonstrating the inherent ability of each individual to belong to multiple communities at once.

When a person is seen as a proxy for a group, he or she is stripped of his or her humanity and forced to bear the weight of all of our fears, prejudices and preconceptions. The White House recently launched My Brother’s Keeper, an initiative to address the persistent opportunity gaps faced by boys and men of color. I believe that in order to improve the lives of African American males, “blackness” must cease to be seen as a simple, monolithic concept. So, too, with masculinity. Ultimately, “Question Bridge” is not about black males, but about people. It shows us what happens when we turn people into categories and how that affects not only the ways we see people, but the ways they see one another and themselves.

Chris Johnson, Hank Willis Thomas, Bayeté Ross Smith and Kamal Sinclair, Do You Really Feel Free? from “Question Bridge: Black Males,” 2012. Produced by Jesse Williams, Deborah Willis and Delroy Lindo.

At this moment, there are more African American men in seats of power than ever before. In addition to the president, we have the attorney general, a Supreme Court justice, two U.S. senators and more than two dozen congressmen. African American men hold some of the wealthiest portfolios and lead large international corporations. Yet simultaneously, black men are subject to disproportionately high rates of incarceration, police brutality and violence from other citizens in their own communities.

Furthermore, many African American men feel that they are viewed through a narrow-minded monochromatic lens. The existence of a “black male identity” is particularly disturbing to me because no “black” person had any influence in its socio-historical construction. The concept of “blackness” as we know it was created by Europeans with a commercial interest in dehumanizing people so that they could be traded as chattel. Almost all virtues customarily attributed to a human being were stripped away to serve those interests, and the resulting stigma continues to shape our lives. Its legacy is an implicit bias with real and dire consequences. From the litany of unarmed black men murdered by the police in the last decade, it is clear that it is a matter of life and death.

Chris Johnson, Hank Willis Thomas, Bayeté Ross Smith and Kamal Sinclair, What Is Common to All of Us?, from “Question Bridge: Black Males,” 2012. Produced by Jesse Williams, Deborah Willis and Delroy Lindo.

The problem begins with a cultural myopia that includes African Americans as well. Most people are taught in childhood not to judge a book by its cover; however, at the same time, we are societally conditioned to classify and make snap judgments about ourselves and others based upon generic groupings. For many, change must begin with the media, with its incredible power to shape perceptions. I believe change must begin with African-American men themselves. The problem with having one’s identity defined by other people is that ultimately, you wind up living out their narrative. Whoever is holding the paintbrush defines the picture.

What would happen if black men collectively painted a picture of themselves? How would that complicate the way society sees them and the way we all, as humans, see one another?

“Question Bridge: Black Males” is currently on view at the New York Public Library’s Schomburg Center and the Fabric Workshop and Museum, Philadelphia. In October, it will open at the Rochester Contemporary Art Center (ROCO) and the San Diego African American Museum of Fine Arts.