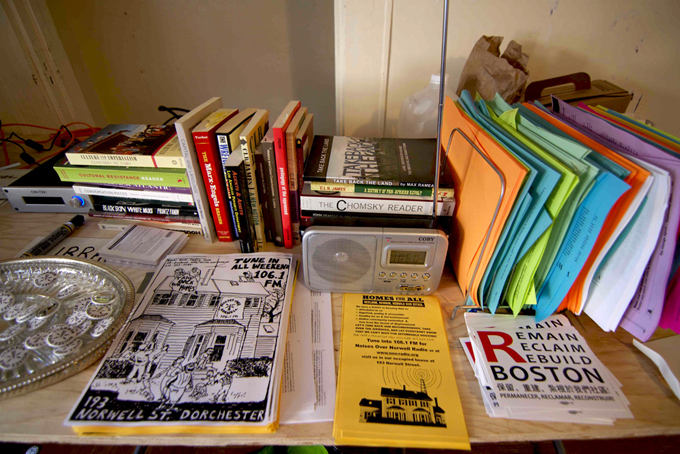

To alert people about the events on Norwell Street, radios tuned to 106.1 FM were hung around the neighborhood. Photo by John Hulsey, 2014.

It has become an all-too-familiar American story. A family receives a predatory loan to buy a home at the height of the housing bubble. In the wake of the 2008 market crash, the property’s value drops. Mortgage payments come to eclipse the cost of the property itself. The family, which has been forced out of its home after falling behind on payments, is evicted. In a new twist to the story, when a private investor buys the property, the family rents the home it once owned—but is again pushed out when the new owner raises the rent. The house sits empty again, until wealthier tenants come along.

In Boston, the most rapidly gentrifying city in the nation, stories like these continue to proliferate. Despite signs that the worst is behind us, as recently as December 2013 9.3 million homes across the United States were still considered “deeply underwater”—that is, the owners owe around 25 percent more on their mortgage than the home’s market value.

In June, Boston-based community group City Life/Vida Urbana moved a homeless family into one such house (owned by Fannie Mae). The artist John Hulsey, together with a team of community members and housing activists, launched a pirate radio station, Noises Over Norwell, inside the house. They broadcast conversations about housing equity and sounds of home on a frequency that had until recently been occupied by TOUCH FM, an unlicensed radio station and important cultural institution in Boston’s African-American community. The occupation lasted a total of three days before local police evicted the residents and shut down the radio station.

Members of City Life/Vida Urbana talk to Michael E. Stone of the University of Massachusetts Boston about the origins of the housing crisis. Photo by John Hulsey, 2014.

For this month’s Editor’s Letter, I spoke with John about the action and how he sees art shaping our collective understanding about the ongoing housing crisis.

Marisa Mazria Katz: You and your team recently undertook a two-pronged action—both occupying a foreclosed home and using a pirate radio signal to broadcast activist messages about the housing crisis—in addressing the deluge of displacement affecting homeowners and tenants in the city of Boston. Can you talk about your strategy and how this multilayered approach might have impacted the community you are working with differently than previous actions?

John Hulsey: If you’ve spent time in cities like Boston, and especially in neighborhoods that have been hit hard by the financial crisis, you’ve seen gaps in the urban fabric: empty buildings, boarded-up structures, houses that once served the purpose of providing shelter lying fallow. This is deeply troubling from an ethical perspective, especially at a moment when so many people, often working 60- or 80-hour weeks, are finding themselves unable to keep up with their mortgages, rents, and medical and other payments, and are struggling to keep a foothold in the neighborhoods where they’ve lived for decades.

What we have here is a key contradiction of our economic system: on the one hand, we have empty buildings punctuating the city’s landscape, and on the other, we have droves of families who are day by day becoming homeless in spite of their best efforts to stay afloat. These same families could afford to live in the available houses if rents were stabilized or home values weren’t subject to the massive fluctuations of a speculative market. Instead the buildings will be scooped up by private investors, who will flip them for a profit, capitalizing on the rebounding housing market and contributing directly to an ongoing dynamic of gentrification.

A wide range of factors have driven us to this situation, including the financialization of mortgage markets, the failure of the social safety net, rising economic inequality and long histories of housing discrimination. We could also look at some of the basic values of the dominant culture. According to the market, a house is a pure financial potentiality, a tool for speculative investment. But from the point of view of the person who inhabits it, it means something different: it’s shelter, a place of repose, the site of many of life’s key events and a long-term investment in a neighborhood. Our culture seems to have skewed so far toward the financial considerations that we have lost sight of what makes a strong, healthy society in the first place. This is a serious political problem, insofar as politics sets the terms by which all of us might live together with a modicum of dignity.

Paul and Renée Adamson moved their belongings into 193 Norwell Street on June 7 to protest Fannie Mae’s refusal to sell the house to a non-profit organization whose aim was to turn the building into long-term affordable housing. Paul and Renée had lost their home to foreclosure and became renters in their former home, but when the investor who bought the house at auction raised the rent, they could no longer afford to live there––even as tenants. Photo by John Hulsey, 2014.

Our occupation of the vacant house at 193 Norwell Street needs to be understood in light of these considerations and in terms of a longer history of grassroots struggle both locally and nationally. In this case our action comprised both an occupation of a foreclosed house and an occupation of an empty spot on the radio dial—Noises Over Norwell. We realized that these issues are interwoven. A couple of months ago, a beloved radio station in the African-American community, TOUCH 106.1 FM—the “fabric of the black community”—was shuttered when the Federal Communications Commission raided its Grove Hall office, not far from Norwell Street, because it had been operating for eight years without a license. Of course this is a complex issue, but the fact remains that the FCC, which regulates the allocation of licenses, didn’t release any new licenses for low-power FM stations in Boston from 2001 to 2013, leading to a problematic backup on the city’s radio dial. This is something that even Governor Deval Patrick has come out against.

MMK: Could you say more about how these two actions are interrelated?

JH: The same communities that are being pushed out of their homes are being shunted out of the media landscape. From a broader view, we can see both shelter and public discourse as basic public goods. If we don’t affirm and protect these as foundational building blocks of civil society, we begin to move in a dangerous direction; our ability to lead meaningful lives, which depends on our capacities to build local support networks and communicate about matters of shared concern, will continue to be constrained by corporate interests whose primary investment is in their own bottom line. So it made sense to think about these two issues together—to take over the physical space of the building and the virtual space of the airwaves, in one single gesture.

A young supporter listens to the day’s broadcast at the entrance to the occupied property at 193 Norwell Street. Photo by John Hulsey, 2014.

City Life/Vida Urbana and its arts collective, which I belong to, have a history of developing creative direct actions to reclaim neighborhoods for displaced residents. In 2010, for an action against Deutsche Bank, we created 72 Hours, in which we projected silhouette images of displaced residents through the windows of a vacant home in Dorchester in order to pressure Deutsche Bank, the owner of the building, to sell a group of properties back to their former owners. In 2011 we set up a community-based installation inside a vacant building whose former owners had been wrongfully foreclosed upon, turning the results into a book, Welcome Back to What Was Already Yours, which was used as a fundraiser for the community that produced it. The following year, for the action Letters to Bank of America, we overlaid the handwritten letters of homeowners facing imminent displacement by Bank of America onto the Bank of America building in downtown Boston in the lead-up to the national shareholders’ meeting in Charlotte, North Carolina. We’ve done other things as well, like creating music videos and even a hip-hop album, The Bank Attack. All of these projects were developed in tandem with larger organizing efforts and were created with a group of homeowners, tenants, community members and artists in order to pressure banks to sell foreclosed properties back to their original owners. Noises Over Norwell is the latest instance of this process.

MMK: What has City Life’s role been in terms of creating models that help stabilize communities affected by this ongoing crisis?

JH: City Life is a grassroots nonprofit that is based in my neighborhood, Jamaica Plain, but with partner organizations around the region and the country. It has developed some truly pathbreaking models for fighting displacement and the destabilization of communities that results from it. Most of the time this involves finding ways to keep people in their homes, whether by putting public pressure on Wall Street banks, creating mechanisms through which homeowners can buy back their homes after foreclosure or building tenant associations to stabilize the rental market. With the Norwell Street occupation we had been trying to get Fannie Mae, which owns the property, to sell the building to COHIF (Coalition for Occupied Housing in Foreclosure), a nonprofit whose goal is to buy up foreclosed properties with the explicit aim of turning them into long-term affordable rental housing for neighborhood residents.

We’re in a new moment of the housing crisis. Even as foreclosures continue apace, many people who were targeted by the first phase of the crisis—receiving predatory loans at the height of the bubble and then falling into foreclosure—are now being bumped to the rental market, where they’re finding it difficult to secure housing as tenants even in their own neighborhoods, as corporate investors capitalize on cycles of gentrification. A recent report issued by the Joint Center for Housing Studies at Harvard University estimated that between 2013 and 2023 there will be between 4 and 4.7 million new renting households nationwide. This has huge implications. In Boston investors are buying up foreclosed homes at auction and either flipping them or raising the rents so high that longtime neighborhood residents can no longer live there. What COHIF and others are proposing is to take some of these properties out of the real estate market altogether, by creating either limited-equity condos or long-term affordable rentals. But Fannie Mae—which owns several empty properties in the area around Norwell Street, in the part of the city that is the most congested with foreclosures—wouldn’t sell to COHIF. This is especially problematic given that Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac are government-run institutions. Here in Massachusetts, they’ve been the target of a lawsuit filed by Massachusetts Attorney General Martha Coakley, who wants to hold these institutions accountable to a state law that prohibits creditors from blocking the sale of foreclosed properties to non-profits that want to sell these properties back to their former owners.

The occupation was kicked off by Antonio Ennis, a longtime neighborhood resident and organizer at City Life, who spoke to the crowd about the struggle for fair housing. The rally also featured members from the Chinese Progressive Association and other Boston community organizations. Photo by Maureen White, 2014.

Earlier you described the phenomenon of displacement with the word “deluge”: the aquatic metaphor is prevalent in these discussions. Advocates of free-market economics would say that the economy functions sort of like the ebbing and flowing of the tides, a self-equilibrating force. But of course the word used to describe home mortgages that are overvalued at current market rates is an “underwater” loan. The way we talk about these things reveals a certain kind of truth: the economic system we’re in gives rise to more than mere surface fluctuations—it generates tidal waves capable of wiping out whole sections of a city.

MMK: What did the community do in response to Fannie Mae’s refusal?

JH: It took the next step, which was to say to Fannie Mae, “We can’t wait for you to do the right thing.” Paul and Renée Adamson, who had received a predatory loan and then lost everything when the real estate market spiraled downward, ended up as tenants in their former home. When the corporate landlord who bought the house at auction raised the rent to an unreasonably high level, they became homeless. With the support of the community, they moved their belongings into the house at 193 Norwell Street to make a simple demand of Fannie Mae: sell this house to COHIF, which will rent it to us for a reasonable price.

MMK: How did you go about setting up the radio station? Did you know that the 106.1 frequency would be available?

JH: With the help of some borrowed equipment and an amazing sound engineer, we installed an inexpensive FM antenna on the chimney and set up a broadcast studio inside the house. The same day that we were tuning the antenna, Charles Clemons, who co-founded TOUCH, called us and asked what frequency we were planning on using. “Have you considered using 106.1?” he asked. I didn’t really think that this would be an option, given that spot’s recent history, but with his imprimatur, it opened the possibility for a really coherent gesture, an opportunity to directly link the issue of media equity with that of housing equity. Brother Charles, as he’s known in the community, joined us for our weekend broadcast and spoke eloquently about how these struggles speak to each other.

Charles Clemons, co-founder of TOUCH 106.1 FM, talks about the connection between displacement and media equity. Noises Over Norwell broadcasted at 106.1 FM, a spot on the dial that has been vacant following the recent shuttering of Clemons’s station by the FCC. Photo by John Hulsey, 2014.

MMK: Was the police arrival and subsequent dismantling of the radio station and eviction of City Life premature? Or did you plan the action with the expectation that it would be short-lived?

JH: Everything we do is part of a broader transformative project. Any action articulates itself through a particular set of tactics in response to a concrete situation. When it comes to things like occupying a house or a spot on the dial, it’s done with the knowledge that it might get disrupted or shut down. Of course, it is crushing when this happens. We would have wanted Fannie Mae to allow Paul and Renée to stay. We would have wanted the community space that we created to continue to function as a space for creative resistance. It is heartbreaking, because Paul and Renée are once again thrust back onto an unforgiving rental market without the ability to find stable housing. Our radio station, Noises Over Norwell, is now packed up in a box while we ruminate over how, if and when we might be able to rebuild it.

At the same time, in the words of City Life member Herbert St. Simon, “every day there’s a new story coming.” By taking this step, we created a new situation, which comes with new sets of obstacles as well as opportunities. The task at hand is to figure out how we can respond intelligently and creatively to the new story in which we find ourselves.

The front rooms of 193 Norwell Street functioned as a community center, with a library and reading corner. Photo by John Hulsey, 2014.

MMK: How do you gauge how much impact your work has had on those affected by the housing crisis? What are your long-term goals?

JH: Inside the community space that we set up in the house, we hung a couple of posters. One was a picture of Malcolm X talking on the radio, and the other was a sign by Steve Lambert that says, “Utopia is not a destination but a direction.” Everything we do is animated by a broader organizing vision, and this project was developed, like all our others, hand in hand with people who have been the most directly affected by the economic policies that we’re living under.

We can talk about impact in a few different ways. On the one hand, are we getting people back into homes? Yes. We have heard from COHIF that Fannie Mae has expressed a willingness to begin selling properties like 193 Norwell Street with the aim of creating more affordable housing. If those sales go through, that would certainly be a victory, and the intense public pressure that we put on Fannie Mae through such a visible action will have played a part in accelerating this process. On the other hand, did we build power to pave the way for still larger victories? Certainly the visibility—and audibility—of the occupation on Norwell Street furthered the collective conversation about displacement and, more importantly, brought the power of organized resistance into view. The residents along Norwell Street, the people who visited the occupation, the guests featured on the radio station and to a certain extent the broader public who tuned in can all be brought together again, around a new challenge. One day there was an empty house on a street where most people are struggling to pay rent and regularly face eviction; the next day there was a big group of people occupying that house and celebrating one another’s presence with broad public support. It’s important right now just to remember that we have the power to do that.

We could also think of this in terms of the experience of the individuals who made the occupation and Noises Over Norwell happen, who come from various class, race, and gender backgrounds. One of the things that art shares with organizing—and for us the radio station was a kind of large public art project—is the ability that both endeavors have to radically open up a space for thinking and being together within the world as it currently exists. It would be a reach to talk about this as some kind of para-utopia or heterotopia, but it’s definitely a space that functions according to a radically different logic, one that opens a set of possibilities and attempts to rearrange what’s sayable and knowable. In the language of impact assessment, we could talk about this as a kind of empowerment, but an empowerment of the imagination.

A model home built by Arthur Sutton, installed in 193 Norwell Street. Sutton is a local artist and neighbor who builds scale replicas of Boston houses in his home workshop on Norwell Street. He exhibited two of them inside 193 Norwell Street for the occupation’s opening. Photo by John Hulsey, 2014.

MMK: Can you give us a sense of the voices featured on the radio station over the weekend? How did you convey the experiences and the thinking that informed your action?

JH: On Saturday, during our big community celebration, we had a round-the-clock roundtable discussion with people from the neighborhood facing displacement, as well as those who had fought back and gotten their homes back. We interviewed organizers, like NTanya Lee from the Bay Area, and academics who study the housing market’s collapse, like Michael Stone. We talked with lawyers, who offered know-your-rights trainings, and scholars, who spoke about the origins of property and land rights laws in the United States.

Over the course of the weekend we aired our “24-Hour Home” project, in which every hour on the hour listeners heard ambient sounds from inside the home of a different person facing displacement: the sounds of people playing the Cape Verdean game uril, a woman giving a haircut, leaky pipes in the basement, conversations around the dinner table, the sounds of a park overheard through a kitchen window. The result was a textured panorama of domestic life, a durational portrait of that which tethers our resistance to our lived realities.

We also played text-based audio pieces that we wrote and performed collectively using a variety of found materials—foreclosure notices, answer and discovery documents, public addresses by Fannie Mae officials. One piece used language drawn exclusively from a recent speech by Mel Watt, head of the FHFA (Federal Housing Finance Agency), and recombined his words into a conceptual poem read by several voices. We wanted to appropriate the language of the bureaucratic banking institution in order to transform it into something altogether strange. The goal with all of this was to render concrete the mechanisms by which power is exerted and to disrupt those mechanisms through language. It was important for us to engage in these experiments from within this site of struggle: that gave the work we were doing with sound, voice, texture and language a different kind of urgency.

MMK: What can art do to shape an understanding about the ongoing housing crisis in this country that journalism or scholarship cannot? And how does art complement and contribute to community organizing around housing issues?

JH: Journalism and scholarship both have important contributions to make in the movement against displacement: articles and studies can reach publics and shift policy on the national level. Within this larger effort, art has a unique and polyvalent role to play, and the work that we’ve been doing within the bank tenant movement is an example of this. For one thing, the arts collective that we have been building within City Life for the past several years is focused on developing socially engaged projects, both large- and small-scale, while at the same time creating a process-driven structure. Our group is made up of a rotating array of visionary individuals, some of whom have art backgrounds and some of whom don’t. We operate in a spirit of trust and commitment to one another, as well as of open-ended experimentation.

A City Life member, who requested that he remain anonymous, speaks with children from the neighborhood for an on-air broadcast. Photo by John Hulsey, 2014.

We work closely with the organizing staff of City Life to come up with projects that will function in tandem with larger organizing goals. All of these projects are built around long-term relationships and shared commitments. The stronger the relationships, the stronger the work.

We could also say that art and organizing share an ability to create the conditions for something that didn’t exist previously to exist. Organizing is about finding a way to reshape the social sphere according to principles that at times stand in opposition to those of the dominant culture. At its core, art is profoundly aligned with this type of project. It is about giving shape to thought—a way of thinking critically and reflexively through form. Both function according to a kind of propositional logic, even in cases in which they are grounded in history, and some of the most interesting socially engaged, collaborative or community-based art of recent decades has been able to move between a descriptive function, which it shares perhaps with journalism, and a propositional function, which I would say it shares with organizing. What’s specific to the work that we’ve been doing is that it’s always situated within contested sites in the city, engaging and expanding upon the histories that are embedded in those places—banks, apartment buildings, homes—in order to sound out some of their deeper resonances. We’ve been trying to find ways of “taking place” in public, opening up spaces for collective reflection, analysis and imagination within sites of struggle. The methods we use are speculative and instrumental, strident and poetic. The work is always driven by an urge to reshape our social and political realities into something more just, equitable and caring—and that is something that all of us richly deserve.