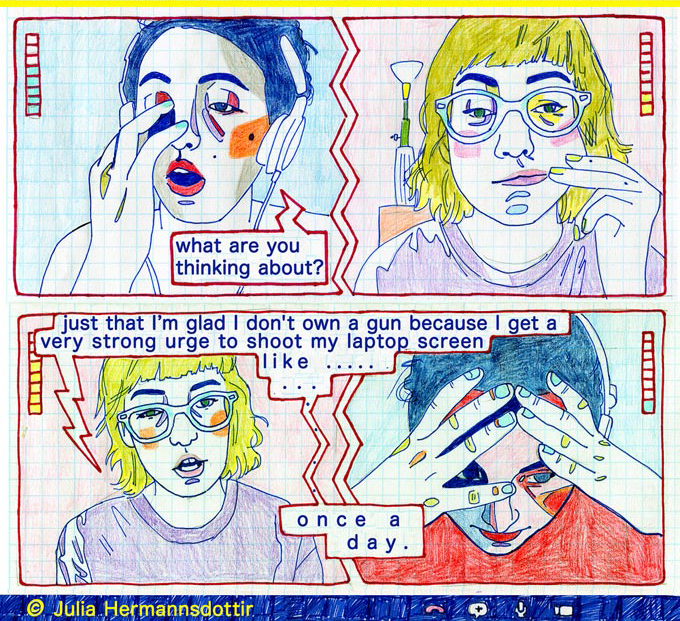

Júlía Hermannsdóttir, Always Thirsty II, 2013.

I don’t have to tell you that we’re cracking at the seams as we expand. We’ve made it quite public. Most recently, we’ve seen trailblazers like RuPaul and Dan Savage critiqued for using the “t slur” and subsequent backlash against these accusations. We’ve seen shaming and humiliation based on difference of opinion, privilege and competition. And our proverbial cup runneth over. We have felt it throughout mainstream media. Facebook. Twitter. All the blogs.

Wait … Am I supposed to sound smart or emotional? Am I supposed to propose the changes we need or just say what I see? Am I supposed to tell the story of my community from my point of view, or am I too afraid to write anything because I think I will be criticized, judged or ostracized for my word choices or intelligence level, my privilege or my tone?

Alas, I come to the problem, and unfortunately I have no real solution. Other than to tell the truths I feel in my heart. Because sincerity is my only option, and my only goal is for peace. Call me sensitive. Call me delusional. Call me old-fashioned. Call me uninformed. Heck, call me a lesbian. I don’t care. This is my op-ed, which will undoubtedly be criticized on the World Wide Web. But it wasn’t always this way.

Pride was the place to realize that you were part of something much, much bigger, and that we all had one another’s backs.

The year was 1998, and I stood in midtown Manhattan to protest the murder of Matthew Shepard. The flyers for the rally had been passed from hand to hand. The black-and-white handouts made their way to each and every one of us, from miles away. The papers were delivered by bodies, and we replied with thousands more, filtering onto the streets of New York City. The crowd was met with the force of the NYPD. Oppressed again. Pushed to the ground. Dragged by our hair. Violently driven into wrongly gendered jails. I froze. My comrades and compassionate leaders were arrested with unnecessary force and aggressive ignorance. But our fight was strong, and we had a plan. To hold each other up and build a wall of support. Lighting candles to commemorate Shepard, we sparked the energy that pulled us together and made us believe that we had power in numbers and that this was never going to happen again.

Since I came out in 1994, I have attended Pride every single year. When I was 16, I even went to every Pride march in Ohio. My dad called me a “gay groupie” for doing so—and maybe I was, but I needed that space. Pride was one of the only “places” where I could find my family. No matter what subset of the queer population you were part of, it was the place to realize that you were part of something much, much bigger, and that we all had one another’s backs.

My Pride experiences were always much more than just a party. We were there to commemorate our foreparents’ struggle at Stonewall, to celebrate the infinite activists who came before us and to enjoy the community that has helped us gain this safe space through visibility and sheer existence. It was important for us to find these moments together, away from being tokenized, criticized, bashed and even arrested for just being us.

Later in my life, I remember sitting in a Chelsea gallery in 2004 and having a multigenerational, multiracial, multigender, multiclass conversation around identity politics. Teaching. Learning. Creating language together. Trying to build a stronger bond and to break a negative stride of separation between the gay male and lesbian communities.

When we sweat together, we grow together.

We were active. We were visible. We were alive. We were growing through change. We certainly weren’t there to break ourselves apart into smaller pieces. We were there to “bridge the gaps,” and it worked. I wondered if perhaps we accomplished our goals of conversation, understanding and dedication to our extended family because we could still remember how we used to hold each other up (as when lesbians cared for gay men during the height of the AIDS crisis). Was this roundtable our last moment of unity? Before we gave in to our smartphones and lost our compassion for one another?

I didn’t own a computer until after I graduated college, around 2002, and to be honest, I wasn’t that interested in having one. Feeling my community physically next to me was more important. Consciousness-raising, crafting, protesting and dancing. That was more my style. When we sweat together, we grow together. But I remember the first time I was criticized on the internet even better than I remember my first kiss. It was 2000, and I was finishing up my last year of college. A friend left a voicemail on my dorm phone saying there was a post about me on a popular message board. I ran to the library to check it out, hammering away at the keys.

I had just started touring with Le Tigre, a feminist, activist band, and my welcome was a post about how ugly—how disgusting even—my gender performance was. My heart pounded out of my chest when I started reading. There were around 300 more comments, and not one of them was in my favor. I printed out the long thread of messages from the library computer. Then I stared at the words for what became hours, wondering what was happening to me, what was happening to the community I had glorified for so many years. There was no context yet for questioning the social effects of the internet (at least not in my world). I had no theory about how this new technology would affect our community. All I saw was anonymous hate. This internet thing felt like bad news.

As the years went on, I struggled with my personal relationship to the web as well as my community’s relationship to it. I couldn’t simply stay offline. I needed the promotional tool for my art, and my computer even became my “paintbrush” (much to my dismay), but still the activist in me, the opinionated thinker I had become known as, was developing into someone so afraid to speak. I feared I had lost my voice. Even now, as I’m writing online about the transformation of queer culture since the internet joined us on our journey, I realize how afraid I am to use the voice that comes naturally to me.

There is not enough celebration of our collective and successful fight.

Of course I’m afraid of “comments” and “threads” that are doing something far from pulling us together. I often wonder whether the harshness of some online personalities comes from being anonymous, whether they stem from obsessions with power or even represent a form of sadism. Maybe it has to do with our long history of being put down, oppressed, hurt and criticized. Maybe it’s a classic “kill your idols” mentality, I don’t know, but the continued threats of violence and public humiliation feel absolutely outrageous to me both as a “victim” and as an invested ethnographer of my family.

I know, I know. This incredible labyrinth that we call the web has also shaped our revolution, immeasurably. It has singlehandedly given the silenced a voice and created communities that were not able to exist IRL. From the sheer power of the more mainstream “It Gets Better” campaign to #GirlsLikeUs (Janet Mock’s popular hashtag empowering trans women of color), we are taking up space and building strength with the help of the internet. We communicate with other cultures and find friends, lovers and intellectual counterparts. We make art. We build our community here. But I believe we also tear it down. My question is, do we have to crack at the seams as we grow?

Some of us have been singled out and shamed for vocabulary. For different methodologies. For having divergent goals or struggles. And so quickly and easily the words are typed. Then sent. Ouch. We used to have to choose more wisely, as a human sat across from us and we could feel their energy. We could hear the crack in their voice. Watch them biting their nails. Now the rush of blood from our pounding hearts to our extremities, our flushed faces and tears, aren’t even in our consciousness. We sit staring at a light box, silenced again.

You see, the internet allows us anonymity. You can create a persona, an avatar, even “catfish” someone. And the excitement of this new technology has certainly impelled many of us to do so. But the internet also creates a false sense of utopia. You are deluded into thinking you have everything you need in this little box. Love, friendship, art and work. So you attach yourself to this space in order to manifest all the power and confidence in the world. Enough to talk down to people whom you would never talk down to in real life. The emotions are lost. You become a shell of yourself.

Yes, there is still more for us to do as a community. But can’t we go there with a smile and thousands of us linking arms? Can’t we get there on the street as well as through a URL?

None of us are perfect. We must hold ourselves accountable for sure, check our privilege constantly and make a definitive decision to continue to learn, grow and most importantly listen to one another. Audre Lorde said it best: “There is no hierarchy of oppression.” And I agree. There must be patience in both directions. You teach me, I teach you. We all grow together. And that teaching will feel beautiful when it isn’t met with an offensive or defensive attitude or a competition over who has suffered more.

Pride has at times been seen as a corporate battleground. It has been deemed mainstream, racist and patriarchal in some towns, has been accused of being built around the idea of a gay dollar—but this month is still ours, and I don’t want to lose it. Pride should be the nonpartisan, all-inclusive celebration of the anniversaries of our struggles and our triumphs. Every year we have more of an opportunity to create the kind of celebration we deserve. But if we sit in front of our computers, without being visible as a team, we will never make it what we want and need.

We built this family out of everything we had. And today I am ecstatic to say that we have even more. More humans and more visibility. More rights and more dreams. But unfortunately there is not a lot of conversation about our success as a team. I read mostly about our divisions—among age groups, gender identities, academic privilege and word choice—how we are becoming split into sectors of the whole we used to be. There is not enough celebration of our collective and successful fight.

That said, I am very hopeful for a more emotional and pleading response to our clashes this Pride season. There are more visible conversations similar to the one I’m proposing, from Gretchen Phillips’s Queerbomb prayer for love to Our Lady J’s Huffington Post op-ed about overpolicing language. Last month, Orange Is the New Black actress Lea DeLaria decided to cancel her performance at the Michigan Womyn’s Music Festival, stating, “After over 30 years of gay activism and as an out, proud member of the LGBTQ community, I do not wish to be a party to infighting … we queers need to find a way to stop this fighting and work together towards our common goal.” Similarly, Kate Bornstein, the pioneering queer theorist and author of Gender Outlaw, made an important observation and request at the Lambda Literary Awards earlier this month: “We shame each other. We’re being mean to each other. … Someone, pioneer a queer community that doesn’t eat its own … please.”

Yes, there is still more for us to do as a community. Let’s get rid of the gender binary altogether, make sure LGBTQI youth don’t end up homeless, make sure hate crime laws in every state cover sexual orientation and gender identity. Yes! But can’t we go there with a smile and thousands of us linking arms? Can’t we get there on the street as well as through a URL? Because we have more bodies. We have more power—and rights. We have more microphones. More ears. And most importantly we have more hearts. Doesn’t that mean we are #winning?