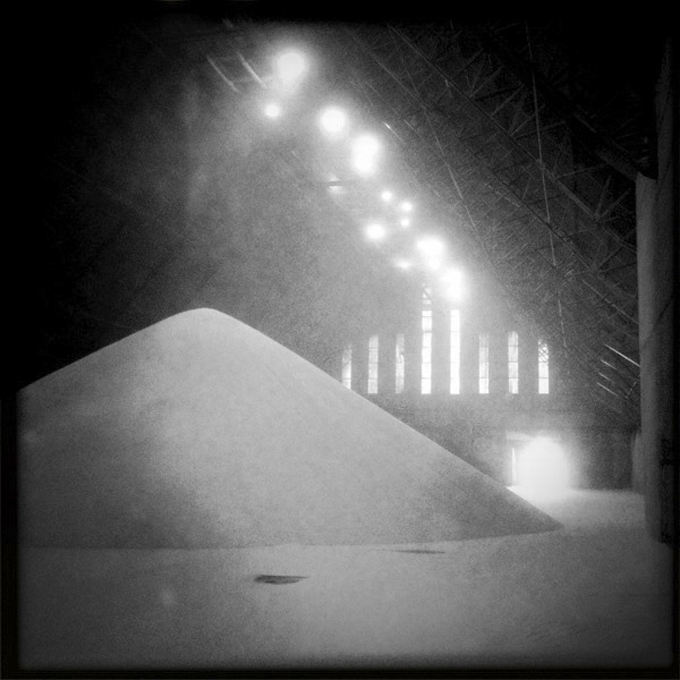

Mounds of sugar in a plant in Santos, Brazil. Photo by Ed Kashi/VII, 2011.

Pour some sugar on meeee, Def Leppard’s Joe Elliott sings.

Like all sugar is pourable. Like there’s only one kind—endless white rivers, soft and powdery. Refined.

Your sugar, Joe, is not my sugar. Your sweet is not my sweet.

White sugar has always been for rich people. White sugar has always been guest sugar, company sugar, sugar for public display. Parlor sugar.

My grandparents’ sugar was the cane. You need strong teeth, strong jaws, to chew sugarcane. The sticks are sometimes too thick to fit comfortably in the mouth. You get purchase on a ridge of juicy, crisp fiber, arrange the fibers crosswise against the blades of your incisors. You position your tongue and the roof of your mouth out of reach of knife-sharp corners. You bite against the grain. If you bite parallel to the fibers, you end up splitting the cane, smaller and smaller sticks in your mouth, saliva running, no juice. But when you get the crunch just right and the surge and gush of sweet liquid—aaaah.

My parents’ sugar was jaggery. Brown rock. Pre-sugar, before the molasses is spun off from the crystals by centrifuge. Made from coconut or date palm sap or sugarcane juice, boiled to syrup, then hardened and chopped into blocks. As a child I had the task of grating the large hunk down into soft, crumbly shavings for cooking. The gritty, melty sweetness of it, shot with undertastes of minerals.

I grew up with yellow-gray Kenyan sugar, made in Mumias, in western Kenya. Thick, coarse grains that sucked moisture from the air to bind into dense lumps that had to be battered and chiseled apart into scoopability. My parents bought a silver tea set once, from a white expatriate family leaving Kenya. We really had no use for it. Our tea was chai: milk, water, tea leaves, sugar and masala boiled together in an aluminum sufuria until it reached the brown hue of a mud-laden river in the rainy season. In the silver sugar bowl, round as a cherub’s butt, perched on three dainty paws, our yellow-gray sugar looked ugly. So my mother bought imported sugar cubes, sparkly white, not knowing you serve those with tongs. The bowl of our silver sugar spoon, its handle elegantly curved, was too deep to lift out sugar cubes. We filled the teapot with already milked, already sweetened chai and never noticed the bemusement on the faces of white visitors.

It takes bones to get sugar white. Thousands of pounds of cow bones burned to bone char are used to bleach sugar in processing plants. My Hindu parents, for whom beef was the ultimate taboo, did not know this when they proudly displayed white sugar lumps in their silver sugar bowl.

Pour some sugars on me. Make them sticky, dense and brown. Make them juicy, fibrous, weapon-sharp. Unbleach the sweet.

Work those sugars, baby. Force them back through bone. Meld them back to rock.

Some of us take our sweet dirty. Extracted. Not poured.

Read more pieces related to the themes Kara Walker explores in A Subtlety: Edwidge Danticat: “The Price of Sugar,” Tracy K. Smith: “Photo of Sugar Cane Workers, Jamaica, 1891,” Ricardo Cortés: “The Act of Whitening” and Jean-Euphèle Milcé: “To Drink My Sweet Body.”