Kampala, Uganda – A gay Ugandan sex worker in her small shared room. Many of her roommates were forced to flee their houses, and turn to sex work, when their families found out their sexual orientation. Photo by Bénédicte Desrus, 2011.

It’s never been safe to be gay in Uganda. In this east African nation, homosexuality is punishable by up to 14 years in prison and gay and lesbian advocates have faced perennial harassment by authorities. Still, before the country’s notorious Anti-Homosexuality Bill was proposed in 2009, it was not uncommon to see two straight men holding hands. And for gays and lesbians who stayed quiet about their sexuality, it was at least possible to avoid identification and harassment.

After the introduction of the bill, which would institute the death penalty for the offense of “aggravated homosexuality,” the situation for the Ugandan LGBTQ community became exponentially worse. While the legislation has languished in parliament for four years, still never having made it to debate, its public announcement provided license for all manner of discrimination against gays. In the bill’s wake, people in the gay community faced eviction, job loss, estrangement from their families and physical and verbal assault.

Kampala, Uganda – Auf Usaam Mukwaya is a 26-year-old gay man and gay rights activist. Because of that, he has been arrested, jailed, abducted and tortured. He has also endured constant homophobic taunts from his neighbors since he was outed in one of the local papers and his face was shown on television. It became impossible for him to fight back, so he had to flee the country for his own safety. In June 2010 he arrived in France, where he received political asylum. There he founded the African Gay & Lesbian Organization Against Homophobia (AGLOAH), an organization of committed African gays and lesbians willing to fight homophobia in Africa. Photo by Bénédicte Desrus, 2010.

Kampala, Uganda – A homosexual witch doctor performs a ceremony with friends to prevent the passing of the Anti-Homosexuality Bill in the Uganda Parliament. Photo by Bénédicte Desrus, 2010.

Kampala, Uganda – Grace and Deborah, both 25 years old, met in Kampala five years ago. Today they live in a shack in one of the capital’s slums. “In public we never show we are together.” Their families are not aware they are together or that they are a couple “But they suspect it,” says Deborah. To avoid persecution, Deborah chose to leave her “fiancée” for more than a year. She settled in with a boy from her village. But once she became pregnant, she ran away. Today she brings her five-month-old son, Ryan, to see Grace. “But we will never be able to tell him the truth,” says Grace. “It’s too dangerous.” Photo by Bénédicte Desrus, 2011.

Frank Mugisha, of the advocacy group Sexual Minorities Uganda, explained that the bill brought with it harassment for gays and lesbians who had previously lived peacefully in their communities.

“I’ve been to two rural areas where I asked the people, why did you choose to give these people [gays and lesbians] to the authorities after living with them for a very long time, and they told me because Uganda has come up with a law that you are supposed to arrest homosexuals,” said Mugisha in 2010. “These are people who have grown up in the same place, lived in the same place and for over 15 years been known as homosexuals and have never been harassed—but when the bill was introduced, they were harassed.”

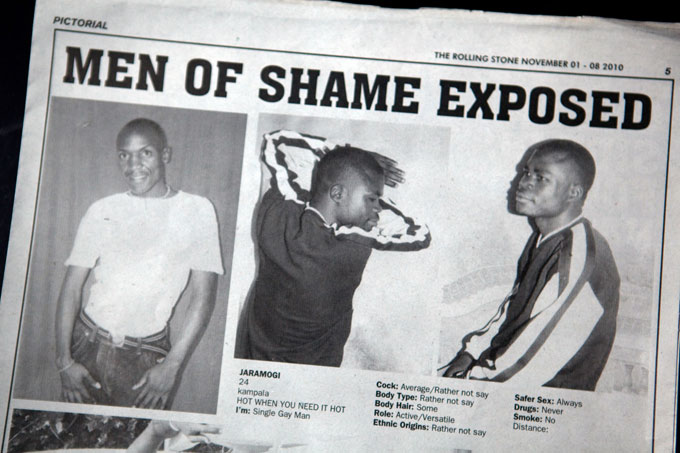

In one particularly high-profile incident, a Kampala tabloid, Rolling Stone, outed several gays and lesbians under the headline “Hang Them.” Among those pictured were a Ugandan bishop supportive of the gay and lesbian community and a lesbian who was later stoned by her neighbors.

Kampala, Uganda – The Ugandan newspaper Rolling Stone first attracted international attention in October 2010, when it published a list of the country’s 100 “top homosexuals” with the front-page headline “Hang Them.” The pages of that edition featured the names, addresses and pictures of several alleged homosexuals, some of whom were reportedly attacked after their involuntary outing. Although Uganda’s Media Council ordered the paper to cease publication, it flouted this command, coming out with another edition on November 1, 2010 that blared the headline “More Homos’ Faces Exposed.” In its November 15–22 2010 issue, Rolling Stone blamed “homosexuals living abroad” for the deadly attacks in Kampala that July, even claiming that gays from the Middle East paid Somali terror group Al-Shabaab to bomb Kampala due to outrage over the Anti-Homosexuality Bill. Finally, the publication blamed gays for funding the Lord’s Resistance Army, which has committed atrocities in the north. Gay activists filed a petition in court to restrain the tabloid from further publication of pictures and anti-gay stories, and sought the cost of damages incurred following the publication of the article. These articles were published near the one-year anniversary of the proposal of the Uganda Anti-Homosexuality Bill. Photo by Bénédicte Desrus, 2010.

The 2009 bill, introduced by a backbench MP of the ruling National Resistance Movement (NRM) party, quickly drew condemnation from the international community, with President Obama referring to it as “odious,” and both the United States and Britain threatening to cut aid if it was passed. No doubt fearing a loss of the aid that still comprises over 25 percent of the country’s budget, Ugandan president Yoweri Museveni distanced himself from the legislation. It stalled in parliament, dying when MPs went on recess for elections.

Then in 2012, a modified version of the law, which removed the death penalty but retained jail terms of up to life in prison, was introduced. Prohibiting the “promotion” of gay rights, it would punish anyone who “funds or sponsors homosexuality” or “abets homosexuality.” The bill has remained in the draft stages in the parliamentary and legal affairs committee of Uganda’s parliament for over a year. The committee’s head has admitted that it is not a priority.

Still, the bill enjoys widespread support in Uganda. In a country where 85 percent of the population identifies as Christian, Ugandan pastors have been among bill’s most vocal supporters. As a result, homophobia has become almost universal.

Jinja, Uganda – A Ugandan religious leader reads from the Bible during an anti-gay rally in the industrial city of Jinja, east of the capital, Kampala. Photo by Bénédicte Desrus, 2010.

Kampala, Uganda – A Ugandan worshipper cries after pastor Martin Ssempa screens what he called “gay porn” to support the Anti-Homosexuality Bill during an anti-gay rally at Christianity Focus Centre in the Mengo Kisenyi district of Kampala. Photo by Bénédicte Desrus, 2010.

Jinja, Uganda – Demonstrators during an anti-gay rally in the industrial city of Jinja, east of the capital, Kampala. They carry banners and signs with homophobic messages like “Sodomy = Death” and “Homosexuality Breaks Family.” Some religious and political leaders are pushing for the death penalty for people who have gay sex with disabled people or minors, or while being HIV-positive. These figures have garnered support for the anti-homosexuality bill by holding numerous hate-filled rallies. Each day that no decisive action is taken to throw out the Anti-Homosexuality Bill, it encourages homophobia to spread and allows political and religious leaders to scapegoat the LGBT community for society’s ills and their own personal gain. Photo by Bénédicte Desrus, 2010.

While much of Uganda’s homophobia is homegrown, people in the gay community in Uganda blame an American for the bill’s inception.

Scott Lively, a conservative evangelical pastor and author of a book called The Pink Swastika, came to Uganda in early 2009. At a conference organized by Uganda’s Family Life Network he described the gay movement as an “evil institution.” A coalition of Ugandan gays and lesbians have brought a lawsuit against him in the United States for allegedly committing crimes against humanity by inciting the persecution of homosexuals in their country.

Meanwhile, in the four years since the bill was introduced, reasons for hope have emerged in the midst of persecution. The increased oppression has actually caused some formerly closeted gays and lesbians to come out, explains John Wambere of the gay rights organization Spectrum Uganda. “When the bill first came out, people were scared and they went underground. Of late they have gained confidence and they have come face to face with reality,” he said.

Kampala, Uganda – More than 100 gay Ugandans and their supporters packed a hotel conference room in Kampala on Valentine’s Day in 2010 to talk about the Anti-Homosexuality Bill that threatens all of them. Many of the speakers were pastors, including an Anglican bishop from Uganda and two Unitarian ministers from the United States. Everyone who attended the meeting was offered a red T-shirt with a rainbow heart on the front. Photo by Bénédicte Desrus, 2010.

Kampala, Uganda – One of the few bars qualified as a safe zone by Uganda’s gay community. Photo credit: Bénédicte Desrus.

Gays and lesbians have also found increasing support among their fellow Ugandans. Wambere says he himself has seen a change in his own family’s attitude toward him. “I used to have a lot of issues with them, but now they have come to accept and live with the fact [that I am gay].”

Being gay in the country is still not without risk, and Wambere says the LGBTQ community won’t feel safe until the modified bill is dead. But perhaps the biggest evidence that some strides have been made is the country’s second annual pride parade, which occurred in August. While the first event was marked by arrests, this year’s celebration, complete with colorful costumes, was allowed to proceed without incident.