Edward Burtynsky, Silver Lake Operations #2: Lake Lefroy, Western Australia, 2007.

The below panel conversation, which took place at New York City’s WNYC Greene Space on Monday, November 4, 2013 as part of Marfa Dialogues/NY, has been edited for length and clarity.

ANNE PASTERNAK: Before we begin, I want to tell you a little story. Last Tuesday Maya called me. She was in a frenzy. She’s like that whenever she’s excited. So when she bypassed the usual niceties like, “Hi Anne. How are you? How’s the family? What’s going on?” I wasn’t offended. Instead, I knew to open up the computer fast or find a pen. She had 100 brilliant thoughts that she needed to share in rapid succession. I begged her to slow down and wait a moment so I could get my stuff together. She could not oblige me. She was too excited about the potential of tonight’s conversation—the potential for us to consider a very important question: “How can art help us be heard?” I didn’t need to hear all 100 points. I wanted you to save them for tonight. But that is the key question—one that thousands of artists are asking today. How can art help us be heard on the essential issues of our day? From the shortcomings of capitalism to the eradication of poverty, from education to prison reform, from urban growth to climate degradation, how can art help us be heard? How can art have an impact?

From the shortcomings of capitalism to the eradication of poverty, from education to prison reform, from urban growth to climate degradation, how can art help us be heard?

Abraham Lincoln once wisely observed, “Public sentiment is everything. With it nothing can fail. Without it nothing can succeed.” That means no important political, economic or cultural change can happen without changing people’s minds. And because culture permeates everything, culture is essential to shaping public sentiment. Today’s artists are using countless methods, often untested, to draw us in, tell us stories and help us understand our world and ourselves. Artists are not only making things; they’re making things happen. They’re not just pointing to social issues; they are working to solve them. They recognize they have a lot of power and even responsibility to create the change that they want to see. In the process artists are becoming more central, not peripheral, to our daily lives.

So let’s take a look at how this artist and this environmental powerhouse have each come to their own understanding of how culture can impact public sentiment around climate change. I want us to begin from the beginning. Frances, what was your environmental moment? What was that moment that flipped the switch and made you decide to become the environmental champion that you are?

Maya Lin, Frances Beinecke and Anne Pasternak discuss climate change at the WNYC Greene Space on Monday, November 4, 2013, as part of Marfa Dialogues/NY.

FRANCES BEINECKE: Well, first of all, I don’t think I determined to become an environmental champion, but I did determine to dedicate my life to the environment. I fell in love with a place. I’m sure everybody has a passion for a specific place. Mine was the Adirondacks. It still is. About 45 years ago I first got there and I thought, how can there be such a wild place—six million acres of wild lands in the state of New York, with 20 million people living within just a few hours? And why is it a special place? Because, for over a hundred years, people worked together to protect it. And it still takes that vigilance. So I saw that through a hundred years of people’s advocacy, it’s still one of the wildest places, and the largest park in the United States.

AP: Maya, how about you? What was your moment or place?

MAYA LIN: I think my whole childhood was formed, ironically, by what the Natural Resources Defense Council (NRDC) started around the time of the Clean Air Act and the Clean Water Act. Much of the environmental movement that I grew up with in the early ‘70s is basically what all of you began to fight for. I was not old enough to have read [Rachel Carson’s] Silent Spring, but that book was one of the first cultural artifacts that shaped how the ‘60s and ‘70s thought about the environment. I came across a funny little stamp. The fact that the U.S. government would put out a stamp that would say, “Save our air, save our water, save our cities…”

AP: Can you imagine the government doing that now?

ML: No. The climate has changed. And how many of you remember this ad? At the time, people were just chucking trash out their card windows; that was OK to do. It’s simple, but these images and thoughts coming out of the early environmental movement were something I got caught up in when I was a kid. I remember crying every time I saw the Native American guy crying in this commercial. And today every time I see somebody polluting by throwing something out of a car window I want to tear them to pieces. (Laughter)

FB: But very few people do that now. That is a huge success story: people took action on littering. It shows you that people want to take responsibility. We have to find the means to take similar responsibility on environmental issues today.

AP: Right. We’re going to talk about that. But first I’d like to take the pulse on how things have changed since the ‘60s and ‘70s. What are the big issues that we’re facing today? What stories need to be told to change public sentiment?

FB: Let’s start in 1970, around the time the Clean Air Act and Clean Water Act were passed, when you could see the pollution through your window, on your clothes and in your water. It was very personal in those days. You could smell it. We’ve done a really good job since. Compare New York to Beijing, and you’ll see what a good job we’ve done. The problem is that the issues that confront us today, like climate change, toxics in our environment and the degradation of the oceans, are so large that individuals feel they are way beyond what they can take responsibility for. So our challenge now is to bring those huge issues that are affecting all the natural systems on the planet and bring them into people’s communities and homes so they feel like they can make a difference. We’ve got to make that connection.

AP: Is there an example of an arts project, or a design project, that you feel helps that situation?

FB: First of all, I think the visual arts make a tremendous difference. When people see Maya’s pieces, they connect with their environment and they want to be involved. Or think of Jim Balog’s Chasing Ice, a documentary film that is jazzed up with a very accelerated timeframe, so you see this enormous iceberg the size of Manhattan Island breaking off. Those things connect on an emotional level and people feel the changes that are occurring in a different way than if you’re just writing about the facts and figures.

AP: Maya, do you think that the realm of the artist is emotional, or can artists actually bring about real change?

I think you have to touch people emotionally for them to feel like we don’t have a right to do this.

ML: I think in order to initiate real change, you have to draw people’s emotions in. There has always been some debate around this: Are we going to save biodiversity by making economic arguments? Or is it a moral issue: do we have a right? Whether you show a picture of a polar bear that might not be around soon, or of multitudes of species that we are basically pushing off the planet, I think you have to touch people emotionally for them to feel like we don’t have a right to do this.

AP: I think that your work goes even further. I would like to have you talk a bit about how you went from doing memorials like the Vietnam War Memorial to “What Is Missing.” I still refer to “What Is Missing” as your fifth and final memorial. Is that true?

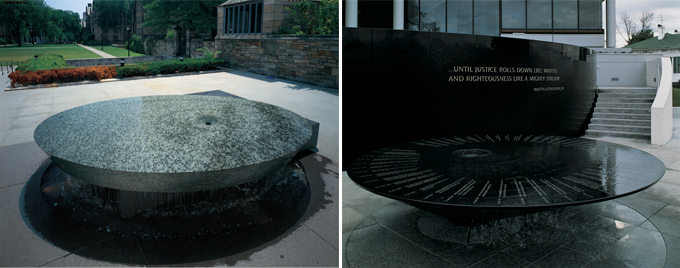

ML: It is the fifth and final memorial. I work in series as an artist. I did the Vietnam Memorial, which was always focused on getting you to be aware about the high price of war. Then came the Civil Rights Memorial at the Southern Poverty Law Center [in Montgomery, Alabama]. I didn’t want to get pegged as a memorialist, but I was drawn to the fact that, growing up in Ohio, I had no idea someone was killed for using the wrong bathroom. It was not taught. Now it is, but it wasn’t in the ‘70s, because the history was happening. So you begin to realize how important it is to remember history. If we don’t remember history, then we’re going to repeat our same mistakes.

Two memorials by Maya Lin: The Women’s Table at Yale University (left) and the Civil Rights Memorial at the Southern Poverty Law Center (right)

Maya Lin, The Confluence Project

Then I did the Women’s Table, and I’m currently working on the Confluence Project, which is all about Native Americans and Lewis and Clark opening up the West. I was asked by the tribes along the Columbia River, “What could you do that talks about our life here? They did not come into an undiscovered land—we were here.” So, as one part of the project, we took parks that basically consisted of parking lots, picnic tables and fake lawns, and we restored them completely into native grasslands and dunes.

AP: For people who haven’t seen “What Is Missing,” will you describe what it is? It’s an extremely ambitious project.

ML: “What Is Missing” poses a question about the link between climate change and biodiversity loss. I started collecting data [on species that are becoming extinct] about 20 years ago. At first I would find roughly one article a year on extinct species. I remember there was a big issue of Life magazine, back when it existed, on all the species that are disappearing. And now you open any paper and you’re clipping five or ten articles a day.

Maya Lin’s project “What Is Missing?” encompasses installations, short videos and the website whatismissing.net. Featured on the right is Listening Cone, a permanent installation at the California Academy of Sciences.

Maya Lin’s “What Is Missing?” in Times Square, a collaboration with Creative Time and MTV

We’ve produced about 75 one-to-two minute films [about species and habitat loss] courtesy of the BBC, National Geographic and the Cornell Lab of Ornithology. We also put in a permanent installation at the California Academy of Sciences, [Listening Cone, above]. We’ll be doing another piece at Cornell Lab of Ornithology, featuring sounds of missing and endangered species. And in partnership with Creative Time and MTV, we took over the MTV billboard in Times Square for the month of April a few Earth Days ago.

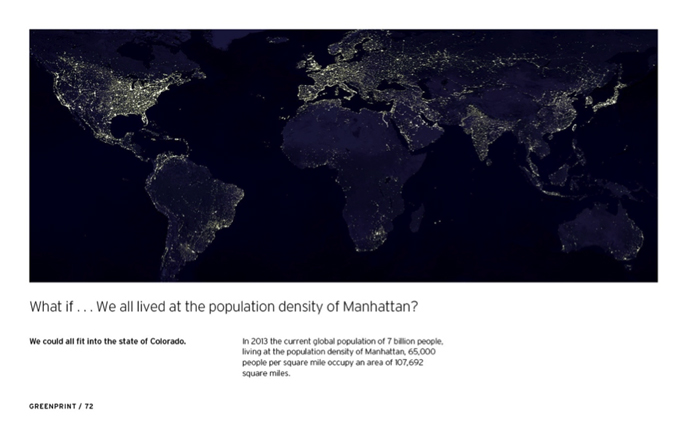

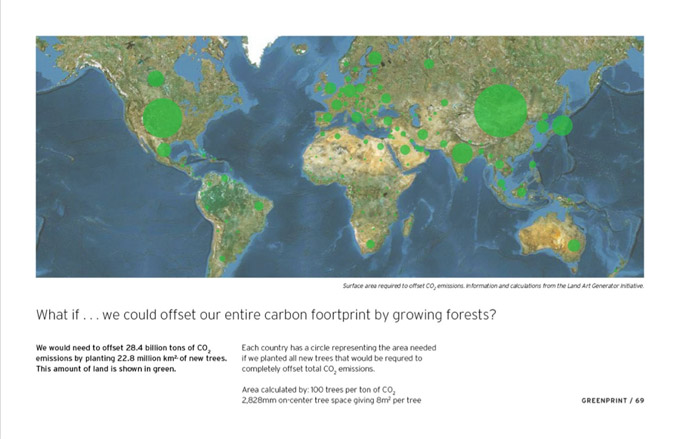

The project asks questions like, can a monument jump form? Can it be wherever it wants to go? Can it exist as physical objects as well as temporary exhibitions? Each Earth Day, I surface with a new iteration. The website, whatismissing.net, pulls it all together with a map of the past, remarking on what we’ve been losing, and a map of the present that links to environmental groups and shows what they’re doing. The final piece is called Greenprint, which is what I’m hoping we’ll talk about a bit today. I always start with this question: if we all lived at the population density of Manhattan, how much space would seven billion people take up? The answer is [the same amount of space as] the state of Colorado.

Maya Lin, Greenprint, from “What Is Missing?”

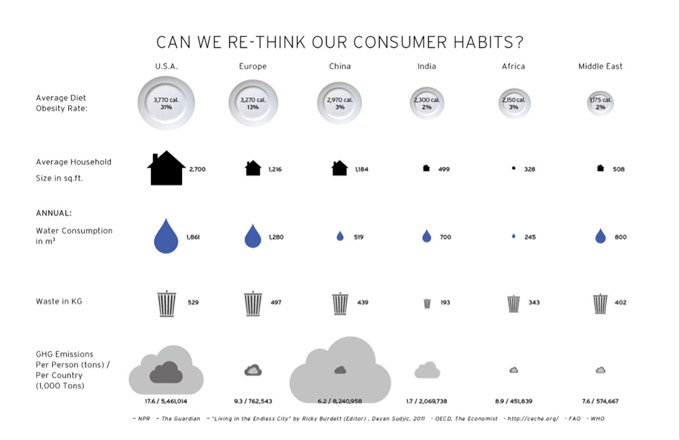

Greenprint is about plausible future scenarios of what the world could look like by 2050. Of course, we’re not saying come on over to Colorado. But literally, if this is all the space that 7 billion people take up living at the density of Manhattan, which is not a bad city to live in, is it really a question of population or is it a question of land use and resource consumption? 50 percent of us live in major cities today. By 2050, 75 percent of us will. So if we focus on the 200 most populous cities of the world, that would represent nearly 75 percent of all greenhouse gas emissions. If you green those cities, you’re heading in the right direction.

FB: To address climate change we have to reduce our emissions, and it will require serious will to shift from a fossil fuel-based economy to a renewables-based economy. You need a lot of people engaged in the game. Why did Earth Day matter in 1970? Because tens of thousands, if not hundreds of thousands of people, who took to the streets. We have to connect with people in such a way that they take to the streets and demand political change.

These issues aren’t simply environmental issues—they’re social issues of the broadest scale.

So now we’re working with the sports industry because, guess what? Many more people in this country watch sports than read science articles. We want that fan base to know that it’s possible to go green. If you go to a sports stadium with solar panels and efficient water features and no one’s using paper, people are going to say, hey, my team is doing this, and do what their teams suggest. They’re much more apt to follow what their sports team does than what NRDC tells them.

Now, we have a million members who are very connected with us and they’ll listen, but in the United States, you need tens of millions of people involved. So you need to reach them where they go for their information. We need to work with artists, we need to work with sports teams, we need to work across all sectors because these issues aren’t simply environmental issues—they’re social issues of the broadest scale.

ML: At this point in time, I wonder, is it art that can make a difference or is it marketing? I believe we’re in the right, but you still have to sell it.

The United States spends the most money on environmental causes. At the same time, Americans’ carbon footprint is ridiculous, even with only 300 million people. We’re having the biggest party on the planet, and everyone wants to consume resources just like us. Much of China hasn’t even begun to enter the middle class. What right have we to say, “Do as we say, not as we do”? More and more, I think we’re going to have countries saying, “Your fault, not my fault.”

I don’t think we can sit back and say we can’t change behavior, but realistically, can you get elected as a politician today asking for sacrifice? We can barely get a tax on gasoline. At a national level, we’re logjammed. On the other hand, cities and states are really moving. Look at New York City; look how much has been happening under Bloomberg: this is one of the greenest cities right now. There’s a huge plus there, and we’ve got the technology to change things around quickly. But we do have an intractable political system at a national level.

FB: We absolutely do. But we can’t let that deter us.

ML: That’s right.

FB: That’s why cities are really important. People feel very personal about their communities. We can begin to reduce our emissions. The president can do it using the Clean Air Act. We’re going to do everything we can to make sure that happens, because Congress is not yet prepared to do anything. Eventually it will, but only if people get involved on the ground level. They have to let politicians know that they expect them to act on climate and will hold them accountable if they don’t.

People understand the economic impact of climate change. We did a study last year that showed the United States spent $100 billion on disaster-related events, between Sandy, drought, tornadoes and fires. That’s simply unaffordable. We cannot spend $100 billion a year and rising on disasters. We have to do everything we can to prevent those expenditures. And the more we look at the impact and the cost—not only in dollars, but also the human cost—that is how it’s going to eventually change.

Maya Lin, “What Is Missing?”

ML: I also think we should showcase where it’s being done best around the world. We’re slightly competitive as a species, so what country is the most advanced in solar energy?

AP: I really wonder if stories about other countries help. It didn’t help with health care; it hasn’t helped with checks and balances on our capitalist system. I remember a TED talk this year that mentioned an energy company in California that wanted to create a campaign to encourage people to save on electricity. They had graduate students who did this test in various neighborhoods. And the first attempt was something like, save on your electric bills and you will save money. And it didn’t change any behavior. And then the next one was something like, save on electricity because it’s good for the environment, and it didn’t change any behavior. You know what did?

ML: What?

FB: Your neighbor.

AP: That’s right. Save on electricity because your neighbor is. That had a dramatic impact on people’s behavior. So if you can create…

ML: Competition.

AP: But not Sweden’s doing X—but your next-door neighbor or your peer at the cubicle next to you. How do we take those strategies to really build community?

What is it about human behavior that’s going to connect? The more we can understand that, the more successful we’re going to be.

FB: There’s a great story out of Kansas on that very topic. So, Kansas, not very progressive, not really interested in talking about climate change. A young woman out there was trying to figure out how do we get these Kansas towns to understand why it’s beneficial to be more energy-efficient. So they did this program geared around how Kansas believes in frugality. It wasn’t about reducing emissions because of the changing climate; it was about towns competing against each other to be frugal and reduce waste.

So, to Maya’s point, you’ve got to figure out, what is it about human behavior that’s going to connect? In Kansas it was frugality. Someplace else it might be different. But we need to understand how people look at these issues, how they adopt these issues. And there’s a very interesting social scientist at Yale, Tony Leiserowitz, who analyzes how people look at climate change in a particular state or congressional district. I think the more we can understand that, the more successful we’re going to be.

AP: This is an interesting proposition that presents tremendous challenges for a nonprofit organization, and it signals to me not only the importance of what Maya does by providing information generously and exquisitely to broad publics, but also how diving into local change might be a powerful place for artists to be. Back to the question of public sentiment: how can art change behavior?

Chris Jordan, Midway: Message from the Gyre, 2009-present.

FB: I think it’s about telling stories that help us understand the implications of climate change, and why it’s so incredibly deleterious, through the kinds of images that Maya uses. Art can engage people in a dialogue about climate change that does not become a political conflict. I think that’s what art does that policy doesn’t, because in the advocacy world we’re on one side or the other. Art can expand your thinking rather than put you into a box; it can open your mind to different possibilities, which I think is really important.

Recently there have been more and more documentaries on environmental issues, and I have to say that Josh Fox’s Gasland changed the conversation on fracking in the United States. And fracking is an enormously controversial practice that’s really sweeping over the country. Gas is being extracted in people’s front yards without their control because of the different way land and subservice rights are owned in the United States. Gasland really got that story out there and created a movement.

ML: I’m trying to figure out what in the environmental field has shifted perception. When Silent Spring was published, that was huge. And then we’ve got these amazing documentaries that have come out and whether it was Food, Inc. or An Inconvenient Truth…

AP: It changed behavior.

ML: Absolutely. As a country, we were in absolute denial before An Inconvenient Truth. That was a bellwether change. So I’m wondering, in art do we have a capacity to effect change because you have to reach a huge audience. I have an instinct that we should just hire the best marketing people out there and strategize, how do you simplify, how do you reach more people faster? We’re doing it grassroots and we’re effecting a lot of change, but part of me wants to just change at a much larger scale. I’m curious what you think about that, Frances.

FB: Well, this is the work that, as I mentioned, Tony Leiserowitz is doing. How do people understand climate change and how do they connect with it? Initially, we spent a lot of time talking about it as a problem of future generations. That was a mistake because it’s a problem of now. We have to unlearn that.

We basically had paradise—and in one hundred years look what we’ve done.

We have started connecting climate change more directly to public health: for example, there’s a huge asthma epidemic in the country because of coal-fired power plants. Likewise, when you look at the air pollution in China, which is just egregious, and you try to talk about climate change, talk about children dying from air pollution and you’re going to get more of a response. So as we’re talking about air pollution and asthma, we’re getting at the climate. Or if we’re talking about the droughts and why farmers are having trouble this year, we’re also getting at the climate.

AP: And how do people learn? Because we’ve already been through devastating changes, and more tensions over food shortages and whatnot are sure to come. Yet we still have this fascinating phenomenon where it can be 70 degrees in January in New York and not one weatherman will say the words “climate change.” How can we, as a species, not repeat the same mistakes from country to country?

FB: This makes me think, when is it the right strategy to evoke sadness? The campaign of the crying Native American was a deeply sad strategy. An Inconvenient Truth was alarming, and it turned off a lot of people, but for me that worked. Maya, can you show Unchopping a Tree? Because that’s a sad strategy.

AP: So talk to us a little bit about this strategy and what you hope to achieve with this piece?

ML: For me, climate change and biodiversity loss are moral issues. When you put aside all the statistics, in the end we have absolutely no right to be taking out the rest of the planet. We basically had paradise—and in one hundred years look what we’ve done. Now we’re spreading that across the whole globe, which is the discouraging part of it.

FB: Our economy in the last 20 years has been absolutely fueled by overconsumption, obsolescence, so you can’t stop it right away without crashing the whole system. But at the same time we weren’t like this 30 years ago.

I think you can do serious art, and poetic art, but humor is hugely important, too, and art can tap into that. There was a really funny dark comedy called How to Get Ahead in Advertising. It was about how marketers first sell you the chocolates and then make you feel like you’re fat, so then they sell you the diet fads. Consumption becomes a perpetual thing.

Overconsumption is a psychological want: you keep consuming, but you’ll never be happy. We weren’t always like that. Think of the frugality we were taught after World War II. Bic pens came with refillable cartridges. Heaven forbid we would throw them out. Now an electronic good breaks within a year. Try to get it fixed and you’re told, “Oh, why don’t you just buy a new one, it’ll cost you more to fix it.” No, no, no, I want it fixed! And you can’t even find those places anymore that’ll fix it. That’s where we’re at right now.

ML: I think that’s really interesting. We do consume a ton, and we throw away a ton of stuff. The ocean’s full of plastic. It comes from the land and then it gets caught up in the currents in the ocean. At the Rio+20 earth conference there was a big session on oceans. And there are lots of very difficult things happening with the oceans. We’re overfishing, there’s acidification and there are plastics in the ocean. At this conference, everybody could vote on what they thought was the most important issue. There were 300 or 400 people in that room, and many said plastics in the ocean. I was very surprised by that, but actually heartened, too, because there was a real awareness that this wasteful society was affecting the ocean and I thought, if people are worried about that, that’s how you make the connection with them. You don’t know what people are going to connect to. You don’t know why the Keystone Pipeline has captured grassroots concern about climate change because of tar sands coming over from Canada. You don’t know why if you talk to people about the oceans, plastics are on the top of their list. I never know what people are going to connect to, but I figure when you find it, grab it and build on it and change behavior.

AP: Don’t we wish we knew? It would be so much easier if we knew.

ML: We have to at least be open to listening and see where that goes.

AP: So, speaking of listening, we’re going to open this up to the audience, but before we do, I want to ask both of you, if you could wave your magic wand and change one thing right now, what would it be? Frances, you can go first.

FB: The entire political system of the United States. That’s where I’d start. (Laughter.) Short of that, how do we get people to make the environment their political issue when they’re voting?

ML: The way we do that is to take it home, so people are talking about the issues that affect them, and build up from there. Not make it so far off, cerebral, distant… But take the power back. That’s where we have to go with the system.

AP: OK, Maya, magic wand.

ML: Magic wand. Bring back forests and plant new forests. I mean, we could be there overnight. And the beauty is it would start sucking carbon out almost immediately. So if every continent literally planted trees…

AP: Plant trees.

ML: But plant billions of them.

FB: Many, many trees.

ML: Many, many trees.

Climate Reports is made possible by the Robert Rauschenberg Foundation. This series is produced in conjunction with the 2013 Marfa Dialogues/NY organized by Ballroom Marfa, the Robert Rauschenberg Foundation and the Public Concern Foundation.