Andrea Bowers’s installation, “Hope in Hindsight,” on view at Project Row Houses in 2010. Photo by Eric Hester, courtesy Project Row Houses.

Located in Houston’s Northern Third Ward, one of the city’s oldest African-American neighborhoods, Project Row Houses is founded on the principle that art and the community it creates can be the foundation for revitalizing depressed inner-city neighborhoods. The Northern Third Ward, though home to landmarks like the Eldorado Ballroom, where greats like B.B. King once played, has long been plagued by severe unemployment, teenage pregnancy, crumbling structures and drug trafficking. Addressing this situation, Project Row Houses provides programs that encompass neighborhood revitalization, community service and education.

At its founding two decades ago, Project Row Houses comprised 22 houses spanning a block and a half; today it occupies six blocks that are home to 40 properties, including exhibition and residency spaces for artists, office spaces, a community gallery, a park, low-income residential and commercial spaces, and houses in which young mothers can live for a year and receive support as they work to finish school and get their bearings. In recent years, the Third Ward has seen several other revitalization attempts, but many local activists are concerned that lower-income residents will be forced out of their neighborhoods by rising prices.

Below, Project Row Houses founder Rick Lowe shares some of the history of the project and reflects on how it evolved in response to concerns the community expressed. Lowe distinguishes his project from social housing developments undertaken on a large scale, emphasizing its collaborative framework.

When I founded Project Row Houses in 1993, I was working on a purely intuitive basis. I began by talking with a group of six other artists about how to do something that was more than just symbolic—something that had a practical application. Once I identified the houses that became Project Row Houses, I was able to pull other people in, together with local arts groups, community groups and churches. At the time, I didn’t know that we were going to be a community-engaged project because I didn’t really know what that meant. But after I started to work on site, it became obvious it was going to be a community project because people in the neighborhood were desperate to see things happen, and they started to come out and support it.

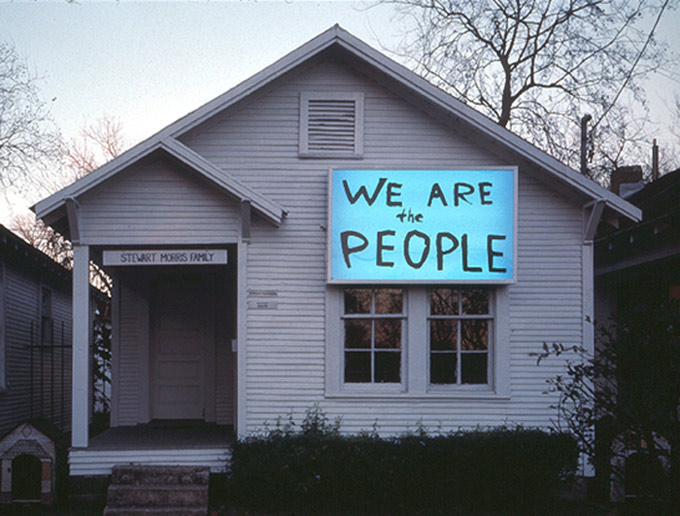

Sam Durant’s installation, “We Are the People,” on view at Project Row Houses in 2003. Photo by Rick Lowe, courtesy Project Row Houses.

I’m very aware that I’m an amateur in most of what I do. I’m not trained in community organizing. I’m not a social worker, an architect, a designer or an urban planner. So I always keep in mind that these are my weaknesses, and I partner with people who are more knowledgeable, especially in the areas where we’re working.

In 1994, as we started to renovate the first 22 little shotgun houses and considered what kind of programs we would feature in each, it became obvious that we wanted artists to be at the center of this community effort. So, working with several African-American artists from Texas (mostly from Houston), we developed what we called an artists’ projects program, merging aspects of arts programs and education programs that are traditionally kept separate.

Early on in this process, I decided that while we would establish what the artists’ projects program should be, the other programs we subsequently initiated would be based on needs we heard about from the community. We wanted to let the people around us bring up the content of what we do, and then figure out how to do it in an aesthetic way that is different and challenging. That’s our role as artists: to think about how to make things interesting, and conceptualize them in ways that add value and meaning.

We weren’t trying to do something to serve the arts community; we were trying to figure out how the arts community could serve this

community.

There are a number of ways that people can tell you what their needs are: as individuals, as groups, with their voices or through actions—if you’re observing. You have to listen on multiple levels. When we developed an after-school education program, it was because community members told us that they needed it, not so much through their voices, but in their actions. Basically, as we worked on the houses every day, and welcomed volunteers every weekend, children were pouring in because they had nothing to do. We had to figure out a context to address that need. So we came up with a program that would offer something like the aunts, uncles and grandparents of yesteryear, who used to look after the children when their parents were at work, until they were no longer able to do that for whatever reason and the kids just started running free.

As we got the artists’ program going and the education program was beginning to move into gear, more and more people from the neighborhood started coming by. They told us that people in the neighborhood needed housing. So we looked at how we could use seven additional houses to address housing issues. We ended up using them for our Young Mothers’ Residency Program.

Before that, the arts community had suggested that we create artist residency housing. But we weren’t trying to do something to serve the arts community; we were trying to figure out how the arts community could serve this community. So after listening to tragic stories about teen pregnancy, rape and the large number of households being led by single parents, we decided we could utilize single mothers as a symbol for the need for housing in this community.

Children play steel pans at Project Row Houses. Photo by Rick Lowe, courtesy Project Row Houses.

There’s now a growing tendency among artists and institutions to try to better understand how to incorporate true community concerns at the root of their work. The institutions are beginning to do this, but it’s still a struggle, because of the legacy of the old museum approach to outreach, which was really about trying to get people from different places to push up visitor numbers, and not about what the institutions could provide for local communities. I think artists understand that there’s a higher value in working in response to community issues, but they struggle to control their own identity and work within the context of the support structures in place for them. Often those support structures don’t allow for the amount of time it takes to pull authentic needs out of a community, because they are more directed toward an artist’s career, or a single project within it, than what the community needs.

Artists generally have been interested in placemaking because of the people at the root of a place.

Today, more and more artists and art institutions are partnering with cities around initiatives for creative economies and so-called “placemaking.” It’s important to note that there are several distinct conversations happening around creative economies and placemaking. My ideas are very much in sync with conversations focused on how art can serve the needs of people within an embattled community, but different from those more geared toward large-scale development. There’s a real divide in the whole notion of creative placemaking in that artists generally have been interested in placemaking, particularly in the shift away from site-specific work, because of the people at the root of a place. Artists have really begun to invest their energy in conceptualizing their work so that it adds value to the people within a place, which oftentimes can have some social and even economic benefits for a neighborhood that’s in transition.

Then there’s another side of placemaking, where institutions are concerned with a larger scale, because their first focus is the economic benefit. This focus shifts their perspective on whom to work with—whom to encourage, nurture and identify creative potential in—which usually become people who are not from the neighborhood. So the impetus of creative placemaking on the city scale or regional scale generally comes from outside of an existing community, whereas artists are generally interested in the creative resource of people within a neighborhood—at least when professional structures do not stand in the way.

Clapboard houses built to provide housing for low-income families. Photo by Eric Hester, courtesy Project Row Houses.

One of the benefits of my art education is to always be able to return to the understanding I have from training as a painter. Just because you can make a painting bigger doesn’t mean that you can make a painting better. And oftentimes people get caught in that trap. They want to make an important painting so they make a big painting. But you can make a big painting and it won’t be any more important than the small one, because the symbolic value of the painting can outweigh the physical size of the painting. Likewise, with community work, we get lost if we bow to pressure from the other kind of placemaking—the one concerned with scale—and we strive for size instead of thinking about the work’s symbolic importance.

We’re trying to create a framework—a form in which questions of

creative economies and community housing can come about from within a community.

When it comes to scale, there are developments that include thousands of housing units and interesting programs. But many of them don’t have nearly as much recognition as Project Row Houses, because Project Row Houses speaks to people across the country, and around the world—about what it means to build a community from within a community. So I would question the single-minded focus on scale. One has to weigh the impact of a housing project that provides 5,000 units, but ends its contributions there, against a project that provides 50 houses as well a framework for discussions around housing that can be replicated in hundreds of communities. I’m not trying to diminish the need for scale, but I also think that as artists producing socially engaged work as art, we have to hold on to where the strength of our work is.

As a piece of art, the form of Project Row Houses reveals something that you lose at a larger scale, when a project is not as thought through and collaboratively produced. We’re trying to create a framework—a form in which questions of creative economies and community housing can come about from within a community—as we provide programs and space to a neighborhood in need.