Footage edited together from the outtakes of Tel al Zaatar (1977, dir. Mustafa Abu Ali, Pino Adriano and Jean Chamoun), showing the aftermath of the 1976 Tel al Zaatar massacre. Courtesy of Emily Jacir, Monica Maurer and Johnny McAllister, AAMOD, Roma.

I think the way to do it is by very minute and concrete descriptions of landscapes of horror and suffering that we are ideologically, minute by minute, being trained to forget or ignore.

If you look at the TV or at the newspapers, you really get the impression that the world has become what is on the TV or in the papers. An intellectual must try to restore memory, restore some sense of the landscapes of destruction—what it’s like to stand on the edge of a village and just bomb into it. Particularly when there are no defenses on the other side.

In 1982, during the Israeli invasion of Lebanon and the siege of Beirut, Italy dedicated its World Cup victory to the Palestinians in solidarity with us. Soon after, I moved to Roma to attend high school, during which time I witnessed the simultaneous ending of Italy’s political Left and the beginnings of the Benetton era. Despite its Berlusconization, remnants of solidarity with Palestine still permeate throughout Italy today, as seen in the network of activist committees that stretch across small villages and major metropolitan areas, and in the work of figures like the late Italian reporter, writer and pacifist Vittorio “Vik” Arrigoni. These vestiges can be traced to once popular mass movements like those backing the Italian Communist Party—the strongest in the West—and the Christian Democratic Party, which, in Italy more than elsewhere in Europe, was linked to the idea of social responsibility and solidarity with oppressed people. Additionally, Italy had Catholic pro-Third World movements and strong religious affiliations with the Terra santa, as well as a shared Mediterranean culture and heritage going back millennia. Thus, support for Palestine remains strong despite a rightward political shift. This past June in Arezzo, Italian football stars gathered together with 1982 World Cup champion players Paolo Rossi and Ciccio Graziani to raise funds for a soccer field in Bethlehem, Palestine.

I worked in the present moment at the same time as I was digging into the past, in a sort of multi-directional way of working, like inhabiting two sides of a split screen.

What’s left of the Left in Italy? In 2008, when Creative Time invited me to participate in its new Global Residency program and asked me to identify a “burning question” that would guide my research, this deceptively simple-sounding question was my response. It encompassed several intertwining issues that have been informing my artistic practice for a long time. One of the main trajectories I focused on was the current immigration situation and the social conditions here in Italy in direct relation to the history of Italian emigrant workers. From the moment Italy became a nation-state in 1861 through to the mid-1970s, an estimated 25 million Italians left their country in search of work. Then all of a sudden in the 1980s, Italy was transformed from a country of emigrants into one of immigrants when it became the recipient of a huge wave of immigration. I wanted to find out how the cultures and displaced identities from all these flows of movement were making a home in Italy and to explore the various cultural negotiations that were taking place in the urban landscape.

Of particular interest to me at the time was the Bangladeshi community in Roma, which is the largest Bangladeshi community in continental Europe. It exploded into being in 1990 due to a concurrence of geopolitical circumstances in the Gulf, Eastern Asia and Europe—including the passing of the Martelli Law, Italy’s first comprehensive immigration legislation. For the first time the right to asylum was possible for all nationalities and not just refugees from Europe. According to scholar Graziella Parati’s account in Migration Italy, the Martelli law remains “one of the last (although flawed) legacies originating from the Italian left of the first Republic.” The law also took into consideration the rights of self-employed immigrants, and provided more flexibility regarding renewal of stay-permits, regardless of work contracts.

Unlike with many other immigrant groups, there are no historical, linguistic, cultural or religious ties between Italy and Bangladesh. The two countries are not linked through the colonial experience as in the case of Libya, Eritrea or Somalia, nor are they geographically close like Tunisia or Albania. Many Bangladeshis had not come directly from Bangladesh but instead from semi-permanent, precarious situations in other countries. With labor recruitment agents leaving many workers stranded in foreign countries with debts, expiring visas and no work contracts, it was better to move on than to return home.

Monica Maurer’s work also focused on the living conditions of immigrant workers in Germany—what she called “the third world in the first world.”

In tandem with exploring Italy’s current immigration issues, I felt it was imperative to excavate Italy’s past, and to tackle Italian migration both internal and external. For 150 years, Italy has pushed a policy of “unification,” which promotes the false construct of a flat, one-dimensional, monolingual Italian identity. Focusing on Italy’s multicultural history, I visited sites in which this incredible diversity has long existed despite the attempts toward so-called unification. I worked in the present moment at the same time as I was digging into the past, in a sort of multi-directional way of working, like inhabiting two sides of a split screen.

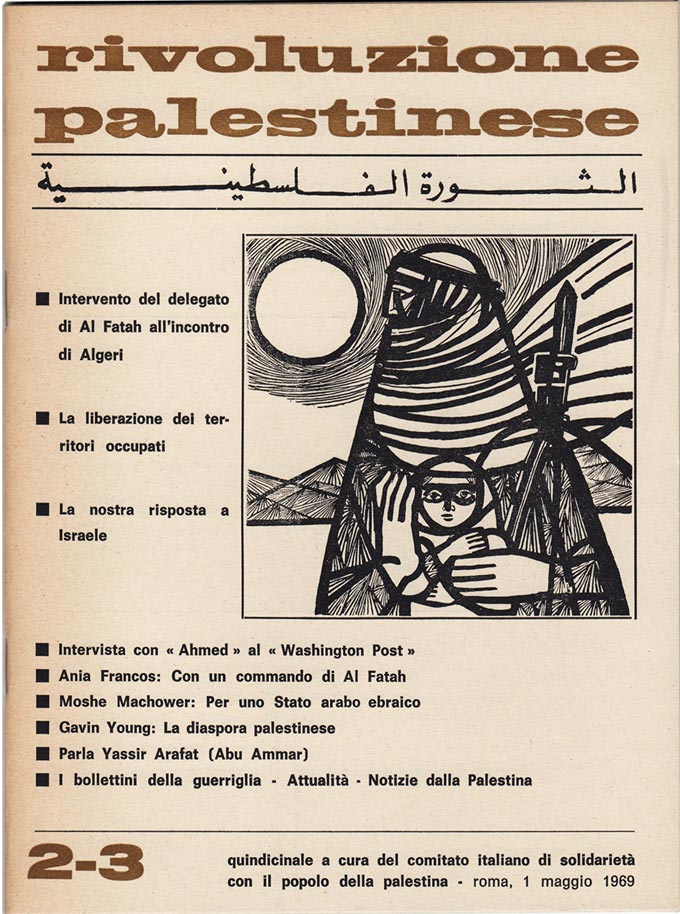

Inexorably tied to all this was an exploration into the trajectory of the Italian Left and international solidarity, in particular in connection to Palestine during the period when Italians embraced the struggle. Part of this research originated in 2004 while working on “Material for a Film,” my project on Palestinian intellectual Wael Zuaiter, who was murdered by Israeli Mossad agents in Roma in 1972. I had begun collecting publications and zines from the 1960s like La Rivoluzione Palestinese (included in “Material for a Film”) as well as conducted research and interviews with the individuals who were part of Zuaiter’s life in Italy between 1964 and 1972.

Emily Jacir, Detail from “Material for a Film,” 2004. Photo © Emily Jacir 2004.

In stark contrast to the Italy of the 1960s and 1970s, with its strong Left, I was traveling within a country where the Right was predominant: the conservative tycoon Silvio Berlusconi was in power, the mayor of Roma was a neo-fascist and anti-immigrant groups like Lega Nord were on the rise. I worked forward and backward in time to reconcile these moments, interviewing those who were active during the 1960s and 1970s about the country’s transformation, at the same time as I attended demonstrations and spoke with present-day activists to find out what roles artists were taking in the promotion of social change. I based myself in Roma and traveled to Palermo, Bari, Venezia, Prato, Terracina, Messina, Piana degli Albanesi and Torino to conduct these investigations. Throughout I conversed with artists, activists, students, writers, politicians, filmmakers, philosophers, professors, immigrants, emigrants, embassy officials and more. In the end I accumulated 92 conversations.

Hearing about the quiet erasure of the history of Italy’s Left made the importance of resisting this parallel amnesia in Palestine all the more poignant.

One common theme that really struck a chord with me as it emerged repeatedly in many of these conversations was a concern for the loss of the history of the Italian Left and the lack of knowledge of its struggles among younger generations. Some spoke of the deliberate attempt to erase moments of Italian history in which principles of solidarity and social justice were the priority. I thought about the destruction of Palestinian archives and history, from the books and libraries looted from cities across Palestine in 1948, to the confiscation of the Palestine Research Center’s entire Beirut archive in 1982 (restored in 1983, following international pressure, minus the film collection), to the seizure of documents and archives from the Orient House in Jerusalem in 2001.

There was one woman in whom all the threads I was following seemed to intersect: my dear old friend Monica Maurer, a German filmmaker who has been based in Roma for the last 40 years. I had long known of her work with the PLO’s Film Unit and had screened her film Born Out of Death (1982) in 2007 in New York. What I did not know until after doing extensive interviews with her was that in the 1960s and early 1970s, her work also focused on the living conditions of immigrant workers in Germany—what she called “the third world in the first world.”

Maurer began her work in Germany with films about Italian immigrants, who, until the mid-1960s, made up the majority of so-called guest workers. She later expanded her focus to include Greek, Spanish, Turkish and Kurdish workers. She had filmed the struggle of Italian workers at the BMW plant in Munich as well as the occupation of the Ford factory in Cologne in August 1973. She had even opened an international bookshop in Cologne in 1974, which carried books and newspapers in the languages of the workers. The exploitation of immigrant labor is a subject that she has been dealing with ever since. In Italy she focused on discrimination against immigrant workers and the transformation of Italy from a country of emigration into a country of immigration.

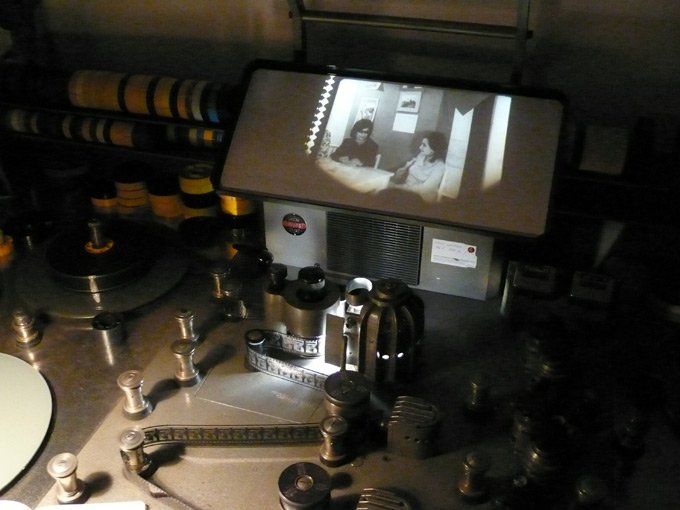

A scene from Giuseppe Bellecca’s La donna palestinese avanguardia della donna araba, on the moviola in the Archivio audiovisio del movimento operaio e democratico (Audiovisual Archive of Workers’ and Democratic Movements) [AAMOD], Roma. Photo by Emily Jacir, 2010. Courtesy of AAMOD, Roma.

Emily Jacir working at the AAMOD, March 2013. Photo by Johnny McAllister, 2013. Courtesy of Emily Jacir.

It was at Maurer’s suggestion that I paid my first visit to the Archivio Audiovisivo del Movimento Operaio e Democratico (AAMOD) four years ago. It was in this institution that all the lines of my research again seemed to converge. I spent days at AAMOD researching and looking at the archive’s extensive visual material from the 1960s and ‘70s on the history of Italian workers, immigrants and their struggles. Among the films regarding international solidarity that I had come to see was the very first Italian documentary made about the Palestinian liberation struggle: Ugo Adilardi’s La lunga marcia del ritorno (1970), on the Palestinian revolution, with a focus on the organization and training of the Democratic Front for the Liberation of Palestine in refugee camps in Jordan. There was Giuseppe Bellecca’s La donna palestinese avanguardia della donna araba (1971), a documentary filmed in Lebanon that focused on the role of women in Palestinian society. In Italian filmmaker Luigi Perelli’s oeuvres I saw my themes again intersecting. Shortly after he made Emigrazione ’68: Italia oltre confine (1968), which documented the conditions of Italian emigrants in Switzerland, Germany, Belgium and Holland, Perelli directed Al-Fatah Palestina (1970), a film produced by Unitelefilm (the production company of the Italian Communist Party). Like Adilardi’s film, Perelli’s Al-Fatah Palestina was shot in Jordan; but Perelli focused on the political organization of the Al-Fatah movement and its daily activities in the refugee camps including the unions, people’s army, and the organization of services, hospitals and schools. Perelli’s film also follows a military action into the Occupied Territories and reconstructs the 1968 Battle of Karameh.

It was during this research in 2010 that Monica and Claudio Olivieri, AAMOD’s archivist and researcher, mentioned that the rushes of a documentary called Tel al Zaatar (1977) had remained in the AAMOD warehouse for the last 36 years, untouched. Directed by Mustafa Abu Ali, Pino Adriano and Jean Chamoun, Tel al Zaatar was the only Palestinian and Italian co-production, a collaboration between the Palestinian Cinema Institution and Unitelefilm. The film’s subject is the August 12, 1976 massacre of Palestinians and Lebanese at Tel al Zaatar, a UN-administered refugee camp in northeast Beirut. The film reconstructs the history of the camp, its destruction and its resistance through the voices of the men, women and children who survived the massacre. They were interviewed and filmed in the weeks directly following the Tel al Zaatar massacre at the end of August 1976, still in the early years of Lebanon’s civil war.

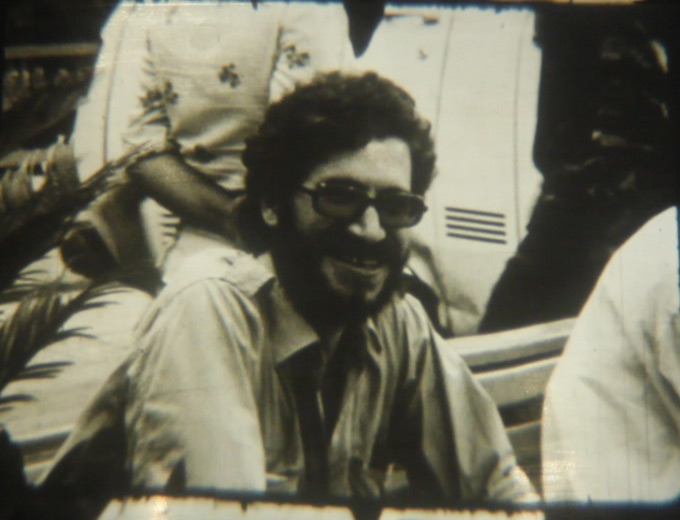

Still from the outtakes of Tel al Zaatar, showing the Palestinian filmmaker Mustafa Abu Ali. Photograph courtesy of Emily Jacir.

Mustafa Abu Ali was one of the main forces behind the Palestine Film Unit (PFU), which recorded Palestinian history—military actions, revolutionary events and everyday life—between 1968 and 1982. Unfortunately, the archive of these films disappeared in 1984 in Beirut, and to this day nobody knows whether they were stolen, buried, burned or lost. Recently, a number of Palestinian filmmakers have been engaged in recovering this archive and Abu Ali’s work in particular. Azzah El-Hasan made a documentary about her attempts to find the archive, Kings and Extras (2006). Annemarie Jacir screened Abu Ali’s They Do Not Exist (1974) for the first time ever in Palestine only in 2003 (Abu Ali himself had not seen the film in over 20 years, until that screening). Between 2006–2007, I conducted several interviews with Abu Ali regarding his work as well as with the archivist and filmmaker Khadijeh Habashneh, who worked on some of the interviews for Tel al Zaatar. But despite these endeavors, when I asked Habashneh to come screen her film at the International Academy of Art in Ramallah in 2010, none of my students had heard of her or the films of the PFU. Hearing about the quiet erasure of the history of Italy’s Left made the importance of resisting this parallel amnesia in Palestine all the more poignant.

Reel from the Tel al Zaatar outtakes. The following was written on this reel: “artigliere – batteria – danza di fucili – Munir-funerale“. In this footage, we see women dancing with rifles, men playing bagpipes, Abu Saleh, Um Ali (Um il thawra, who lost 4 sons), Martyr’s Cemetery (on the outskirts of the Shatila refugee camp in Beirut) and a funeral procession with Mahmoud Darwish, Abu Saleh, Um Ali and many others. Courtesy of Emily Jacir, Monica Maurer and Johnny McAllister, AAMOD, Roma.

It was the remnants of Tel el Zaatar that brought Monica, Ugo, me and a group of Palestinians from Gaza together, four years later, at AAMOD. Over the years, as Monica and I crisscrossed paths in Beirut, Roma and elsewhere, she continually updated me about the numerous initiatives at AAMOD, as well as the growing difficulties in receiving public funding for the safeguarding of its precious audiovisual heritage (particularly alarming given the slowly disappearing narrative of the history of Italy’s Left). Suddenly, this past January, I received an urgent call from Monica regarding AAMOD and the Tel al Zaatar rushes. She informed me of the amazing news that the Italian State Archive had agreed to host the AAMOD archives. She did not want the Tel al Zaatar rushes to be sent over from its storage building in Pomezia before we had gotten a chance to look at them and digitize them, as they had not been touched in decades. In March, she said, everything was to be moved over to the new warehouse hosted by the Italian State Archive. It was an urgent situation and so we immediately made our plan. I dropped everything to go work by her side on this project.

Emily Jacir and Monica Maurer working at the AAMOD, Roma, March 2013. Photos by Johnny McAllister, 2013. Courtesy of Emily Jacir.

We began our work with the 33 boxes that Monica had salvaged, amid freezing cold, from the storage building in Pomezia. They contained everything related to Tel al Zaatar and more, including two reels from Al Fatah Palestina. The reels were in bad shape: some sound reels had actually disintegrated into dust, giving off an intense, toxic odor. Our first step was to divide the boxes into two piles: one of reels in acceptable condition for viewing on the Moviola, and another of the reels that required restoration. In the following weeks we viewed as many reels as possible and designated a priority group to be digitized as soon as we could secure funding. Some sequences were deemed too damaged to save, but I took them out of the garbage can and kept them with me. I asked filmmaker and writer Johnny McAllister to film our work and he generously assisted us in recovering and restoring the reels as well. Some of the reels had literally hundreds of splices that had come undone and that we had to put back together, a time-consuming process requiring a lot of patience.

On April 3, in the midst of this huge effort, ten video artists and filmmakers from Gaza came to take part in a workshop on techniques of preservation and the concepts that guide historical archives. The ten filmmakers were part of the “Vik convoy,” a group of 26 Palestinian artists, athletes and philosophy students from the Italian Center for Cultural Exchange – VIK in Gaza, who had been invited by the Roman Network of Solidarity with the Palestinian People to tour a dozen cities in Italy and participate in the anniversary of the tragic assassination of the pro-Palestinian activist Vittorio “Vik” Arrigoni with his mother in his hometown of Bulciago. Their visit that day was one of AAMOD’s new initiatives to mobilize young people and this “Media & Cinema” group comprised the first Palestinians ever to attend a workshop at AAMOD. The group was welcomed by AAMOD president Ugo Adilardi and Monica Maurer. Afterward, films were screened, including Al-Fatah Palestina, Tel al Zaatar and Ugo’s own La lunga marcia del ritorno, about which he spoke. Then the group had its first encounter with a 16mm editing table, where Monica and I shared our work on Tel al Zaatar. Working side by side with Monica and Ugo and this group of Palestinians who came to Italy through a solidarity initiative, everything seemed to come full circle. My traversing back and forth through time seemed to arrive firmly in the present.

Footage from the Tel al Zaatar outtakes, showing the port of Tyre, Lebanon, with Lebanese and Greek ships, men arriving, people swimming and a war plane above. Courtesy of Emily Jacir, Monica Maurer and Johnny McAllister, AAMOD, Roma.

We continued our work and managed to go through roughly 80 percent of the reels. There were many other amazing discoveries, including Claudio Olivieri’s locating of the original score in Arabic, which had only existed in Italian until then. We found reels that seemingly had nothing to do with the film: for example, Palestinians and Lebanese marching together on January 1, 1971, in Damour, Lebanon; footage taken in Tyre, Saida and elsewhere; training camps; poet Mahmoud Darwish and others attending a funeral; and various press conferences with figures including Yasser Arafat, Kamal Jumblatt, Nayef Hawatmeh and Khalil Ibrahim al Wazir (Abu Jihad). Now our goal is to digitize all the reels before they enter the Italian State Archive. It has been a labor of love for months, and we have only now received a small grant from the Institute for Palestine Studies (IPS), but are still in desperate need of more funding in order to carry out this enormous task. We hope to finish digitizing the films within the next six months, and eventually create a public video archive through AAMOD. Finally, our dream is to give a digital copy of the entire collection to IPS to be safeguarded as part of the Palestinian collective memory.

Still from the Palestinian Cinema Institution’s Tel al Zaatar outtakes, showing the town of Damour, Lebanon on January 1, 1971. Photograph courtesy of Emily Jacir.