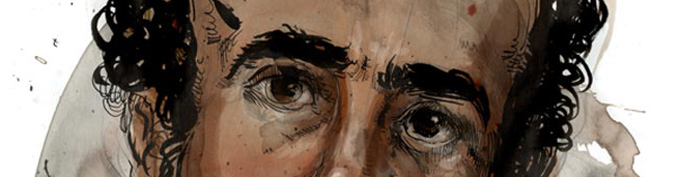

Molly Crabapple, Samir Moqbel (detail), 2013.

America wants to forget about Gitmo.

Sure, we gloat about Khalid Sheikh Mohammed. When I visited Guantanamo in June to cover the 9/11 military commissions for VICE, I drew him through three layers of bulletproof glass. Khalid Sheikh Mohammed is a mass murderer, and we caught him. U-S-A Number One.

But KSM-style terrorists are rare at Gitmo. Out of the 164 men held in the island prison, the chief prosecutor at Guantanamo Military Commissions, Brigadier General Mark Martins, told me that 144 would never be charged with any crime.

They are to be held until the end of the “War on Terror.” But wars on concepts seldom end.

During the invasion of Afghanistan, the United States offered locals $5,000 bounties for turning in terrorists. Instead, we got a mixture of Taliban draftees, guys who shot rifles at Islamic training camps in the 1990s, Uighurs fighting China and, above all, Arabs in the wrong place at the wrong time.

Now, branded by Bush as “The Worst of the Worst” they are to be held until the end of the “War on Terror.” But wars on concepts seldom end.

Of the 144 men who will never be charged, 84 have been cleared to leave for years. But they live in a Kafkaesque legal limbo. In what a Guantanamo spokesman claimed was a concession to the Geneva Conventions, they’re banned from speaking to press.

As of September 2, 35 prisoners are on hunger strike. Thirty-two are being force-fed, a brutal process that involves Ensure being pumped through a tube snaked into their stomachs.

One night, I drank beer with a press officer at Guantanamo’s jerk chicken joint. She described herself as a pacifist in camo. As she spoke about the hunger strike, her tanned, pretty face drew tight. “I don’t know if they’re innocent. I don’t know if they’re guilty,” she told me. “I don’t even know their fucking names.”

Americans see

bogeymen in orange jumpsuits—not men with PTSD, favorite

soccer teams and back problems…

This is by design. Guantanamo’s guards refer to prisoners by numbers rather than names, and are banned from reading their Joint-Task-Force Guantanamo detainee assessments, which WikiLeaks made public. The U.S. government refused to release prisoners’ names until 2006. When I returned to Cuba in August to write a follow-up article for VICE, I visited the prisons for the first time, but I was not allowed to draw detainees’ faces. Americans see bogeymen in orange jumpsuits—not men with PTSD, favorite soccer teams and back problems; families and dreams; loves and legitimate hates.

For a journalist, trying to piece together the life of a Guantanamo detainee involves staring into the bureaucratic unknown. You have JTF-GTMO assessments, filled with feverish claims and torture-induced accusations. (One former detainee, Binyam Mohamed, comes up repeatedly as a source of accusations against fellow prisoners – accusations he made during C.I.A. rendition in Morocco, while interrogators allegedly sliced his genitals with razors. The U.K. government awarded him a million pounds in damages for their role in his torture.) You have their lawyers. If you’re lucky, you have blacked-out intelligence reports. Thanks to a Freedom of Information suit filed by Miami Herald journalist Carol Rosenberg, you know the names of the indefinite detainees.

But why some are approved to leave while others will be held as long as the prison exists? That’s hidden behind a wall of classification.

Since media are not allowed to photograph prisoners at Guantanamo, the only recent images come from photos taken by the Red Cross. The British legal charity Reprieve shared these photos of seven of their clients. Each of these men has been cleared years ago to leave Guantanamo. None has been charged with any crime. Here are their names, faces and, as best I could figure out, their stories.

Shaker Aamer

Molly Crabapple, Shaker Aamer, 2013.

Guantanamo press officers hate Shaker Aamer. Though they are not supposed to speak about individual detainees, they roll their eyes at his complaints of abuse. Believing anything Aamer says, they seem to hint, is for chumps.

Aamer, a Saudi-born British resident who worked as a translator for the U.S. army during the first Gulf War, is married to a British woman. On February 14, 2002, the day Aamer was transferred to Guantanamo, the youngest of his five children was born. Aamer has never met his son.

Aamer is also Guantanamo’s most vocal detainee. As organizer of hunger strikes, he writes scathing editorials for the Guardian. He is a cause celebre in Britain.

Ramzi Kassem, Aamer’s U.S. attorney and a law professor at the City University of New York, told me, “Shaker believes that only through constant civil disobedience and peaceful protest can he retain and assert his dignity and autonomy as a human being imprisoned at Guantanamo.”

“I sometimes feel sorry for these young prison guards at GTMO,” Aamer told Kassem. “They have been trained not to be kind, even where their instincts tell them to be kind. They have been told lies and absurdities about the prisoners to the point that they are shocked that I can speak English and they are still in disbelief that I know bands like AC/DC and that I listened to that band before the guards were even born.

“The guards check the soles of prisoners’ shoes as part of their body search protocol. They ask me to lift up my shoes behind me while I am standing up, like a mule. I have rejected this procedure for years. Instead, I insist on being brought a seat, I sit down, then I stretch out my foot and make the guard get down to the ground on his knees to check the soles.”

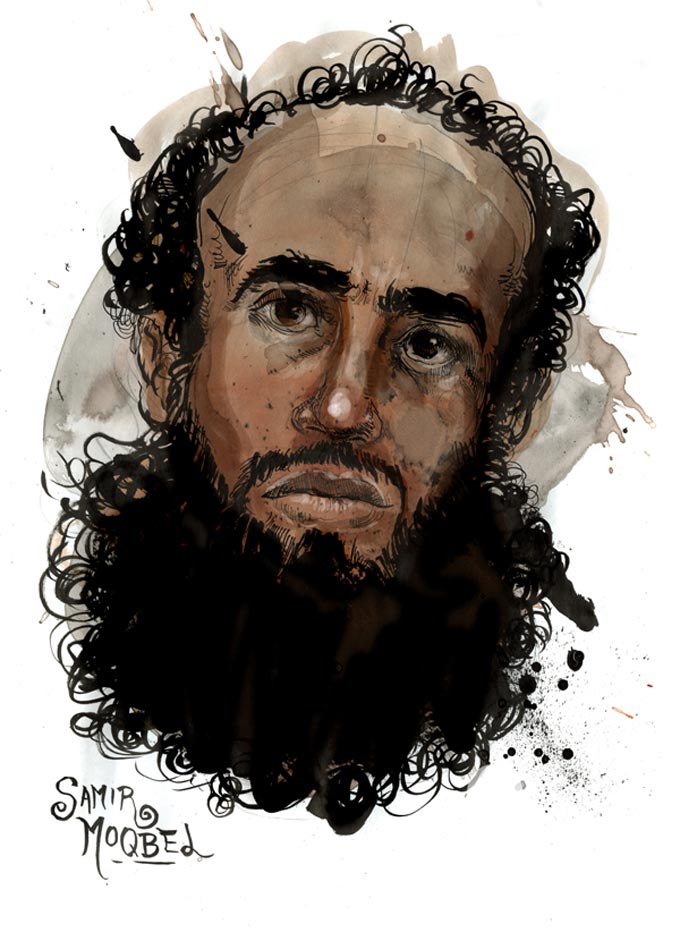

Samir Moqbel

Molly Crabapple, Samir Moqbel, 2013.

Samir Moqbel got his first job at a factory in Yemen at the age of 12. According to his JTF-GTMO assessment, he practiced rifle shooting for four afternoons in 2000, before splitting to Afghanistan to fight the Northern Alliance (a year before we declared war on the Taliban). Because of these allegations, the United States has imprisoned him for 11 years, at the cost of over $11 million.

Moqbel’s lawyers at Reprieve tell a different story. A friend lured him to Afghanistan with promises of better-paying work, and then, when none materialized, tried to convince him to join the Taliban. He was arrested at the Pakistani border, while asking the Yemeni Consulate with help for his lost passport.

Moqbel has been on a hunger strike since March, and is one of the 32 men currently being force-fed. In an editorial in the New York Times, he wrote: “It was so painful that I begged them to stop feeding me. The nurse refused to stop feeding me. As they were finishing, some of the “food” spilled on my clothes. I asked them to change my clothes, but the guard refused to allow me to hold on to this last shred of my dignity.”

In June, I asked Guantanamo spokesperson Captain Robert Durand about Moqbel’s editorial. “Most of what they say short of ‘I don’t want to be here’ is patently false,” he replied.

Twice a day, soldiers shackle Moqbel to a restraint chair, and force a feeding tube into his stomach though his nose. They then pump Ensure through the tube. According to Guantanamo spokesman Lt. Col. Todd Breasseale, as of June he could choose his flavor: vanilla, strawberry or butter pecan.

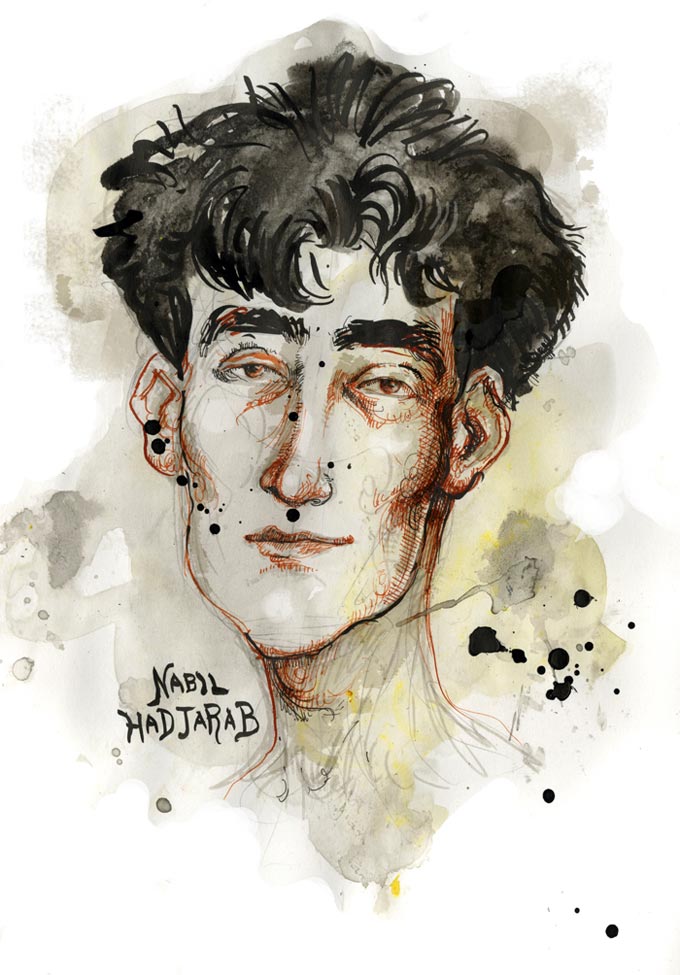

Nabil Hadjarab

Molly Crabapple, Nabil Hadjarab, 2013.

Nabil Hadjarab’s life was shaped by colonialism’s absurdities. Born to an Algerian father who fought on the side of the French, Nabil came to Paris as an infant. While his siblings are all French citizens (one of them even earning a National Medal of Honor in the French army), Hadjarab’s Algerian birth meant French citizenship was anything but assured. On the advice of an immigration lawyer, he left France for England while his residency papers were being processed. Going broke working off the books, Nabil listened to a friend who told him that in Afghanistan, papers were superfluous. Two months later, American bombs hit Kabul.

Like 86 percent of those at Gitmo, Hadjareb was sold for a bounty by Afghans who had every financial incentive to say he was a terrorist. For the next eleven years, he cooperated with U.S. authorities, learned fluent English, worked out and kept his mind on the world beyond Guantanamo’s Camp Delta walls.

In February 2008, the Department of Defense emailed Hadjarab’s council: “Your client has been approved to leave Guantanamo…. As you know, such a decision does not equate to a determination that your client is not an enemy combatant, nor is it a determination that he does not pose a threat to the United States… I cannot provide you any information regarding when your client may be leaving Guantanamo.”

On August 29, the Pentagon announced that Hadjarab had been repatriated to Algeria. Because of travel restrictions, he will likely be unable to return to his family in France.

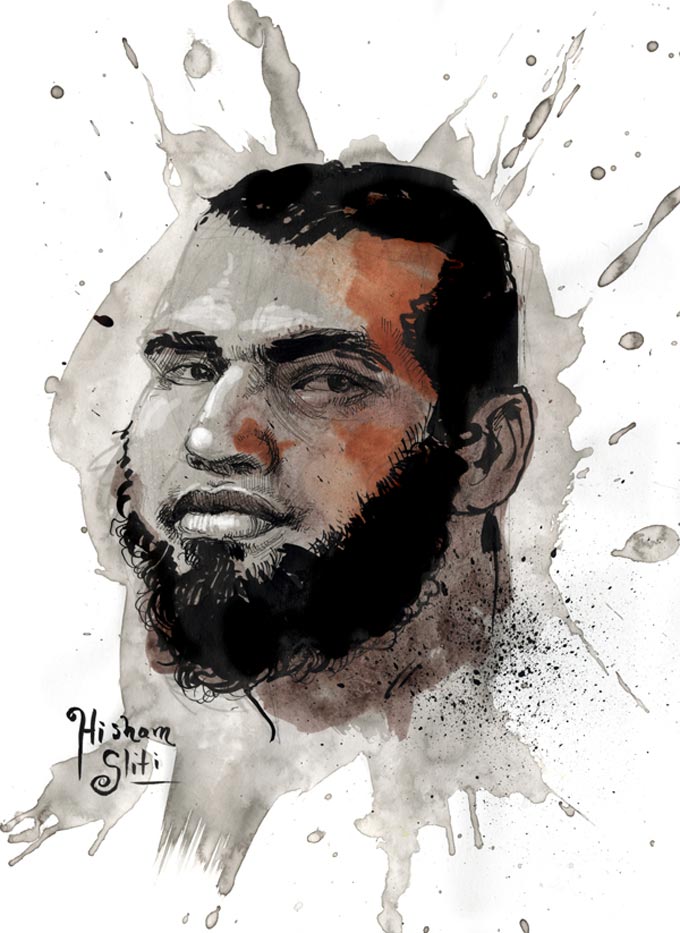

Hisham Sliti

Molly Crabapple, Hisham Sliti, 2013.

When Reprieve lawyer Cori Crider first met Hisham Sliti, she wore a hijab out of respect for his religion. “Why are you wearing that?” he laughed. “You don’t need that here. It’s hot!” Born in Tunis, Sliti moved to Italy looking for work, as many young North Africans do. According to Crider, he spent half her first visit talking about how much he missed Italian women. In Italy, Crider told me, Sliti became addicted to heroin. After a few arrests, a conservative Belgian cousin shipped him off to Afghanistan, so he could kick his habit and get in touch with God. Sliti despised it. Detoxing cold turkey in a sweltering country where everything from sex to cigarettes was forbidden pushed Sliti toward homelessness. Then, America blanketed Afghanistan with flyers offering $5000 bounties for Arabs.

On August 16, 2006, a lead inspector from the Belgian Federal Police told the Department of Defense that Belgium’s investigation of Sliti did not disclose any acts of terrorism. He was just a “Jalalabad junkie.”

Sliti is clean now. “He’s seen the bottom of it all, but is very jovial,” Crider told me. “He gets himself into trouble when he sees people mistreated.”

Sliti has been imprisoned since December 2001.

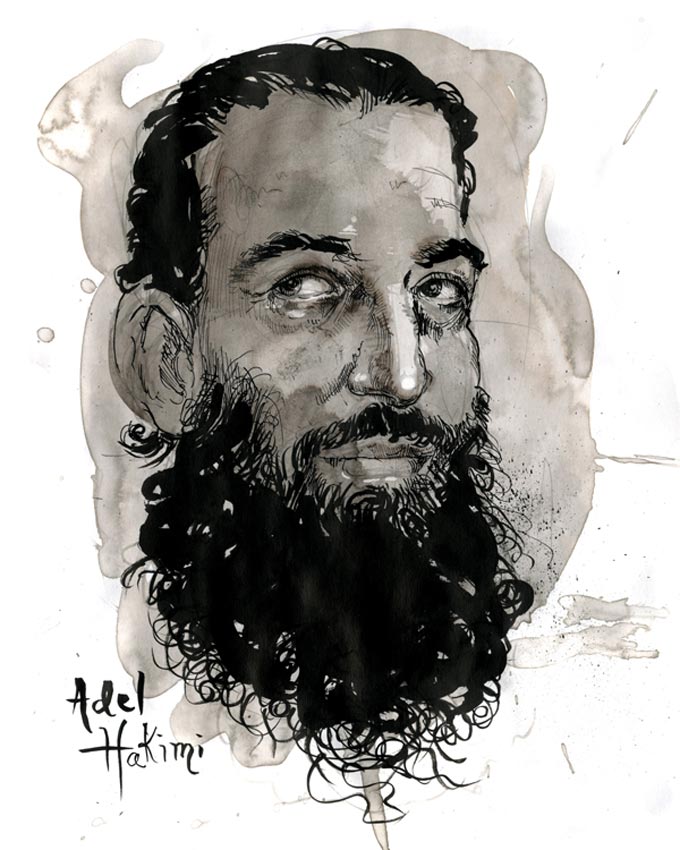

Adel Hakimi

Molly Crabapple, Adel Hakimi, 2013.

In a former life, Hakimi worked as a hotel chef in Bologna. Now, he only smiles when dreaming about setting up a snack stall back in his native Tunis. According to Crider, who represents Hakimi, he “went through some things in Kandahar from which I don’t know if he will ever recover.” By this she means kicks to the head.

Leaving Bologna would set Hakimi on a collision course with the War on Terror. Hakimi claims to have been looking for a Muslim bride in Pakistan. He married an Afghan women, and his new in-laws demanded he move with them to their native Jalalabad. They spoke about opening a restaurant. Hakimi would be the chef.

Hakimi’s wife was pregnant during the American invasion. Before she could give birth to their daughter, Hakimi was kidnapped by bounty hunters.

Hakimi’s JTF-GTMO assessment claims he shot guns at the Khalden training camp three years before the towers came down, ran a guesthouse for Tunisians in Jalalabad and was an advisor to Bin Laden. They further allege he blamed 9/11 on “the aggressive and tyrannical acts of the U.S. and its support of dictators,” and once refused to pass his food tray back to a guard.

When I asked Hina Shamsi, director of the ACLU’s National Security Project, how the public should regard JTF-GTMO assessments, she told me “These are one-sided assessments that are full of uncorroborated information, information obtained through torture, speculation, errors, and allegations that have demonstrably been proven false.”

In 2012, The Guardian filmed Hakimi’s brother Emad in Tunisia. “He caused no harm to anybody,” Emad said, holding a photo of Hakimi’s daughter, Hind. She grinned in her pink sweatshirt. “We pray to God that he will meet her soon,” said Emad, “and hug her just as any father hugs his child.”

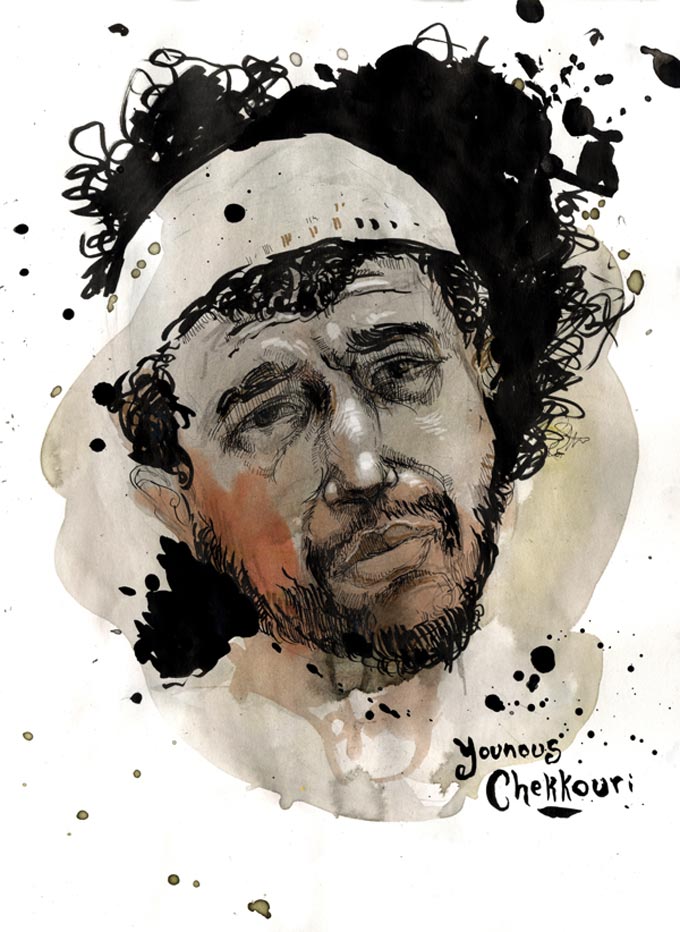

Younous Chekkouri

Molly Crabapple, Younous Chekkouri, 2013.

Born in Morocco, according to Crider, Chekkouri travelled throughout the Islamic world doing relief work. When his younger brother Radwan couldn’t get a job, Younous suggested he join him in Jalalabad. Then, the war started. Wounded by U.S. bombs, Radwan was captured by The United Islamic Front for the Salvation of Afghanistan, and sold for a bounty from his hospital bed. Younous was later captured by the Pakistanis. The two brothers found themselves together in Gitmo. Crider tells me that Younous confessed to wild charges to deflect attention from his brother, who was released from Gitmo in 2004.

In his JTF GTMO assessment, unnamed sources claimed Chekkouri co-founded the Moroccan Islamic Combatant Group (a terrorist group connected to the 2004 Madrid subway bombings) and met Bin Laden. To the JTF, his denial only confirms his guilt. According to Crider, Chekkouri is racked with remorse for suggesting his brother join him in Afghanistan. His first question to Crider during her last visit was, “How is Radwan?”

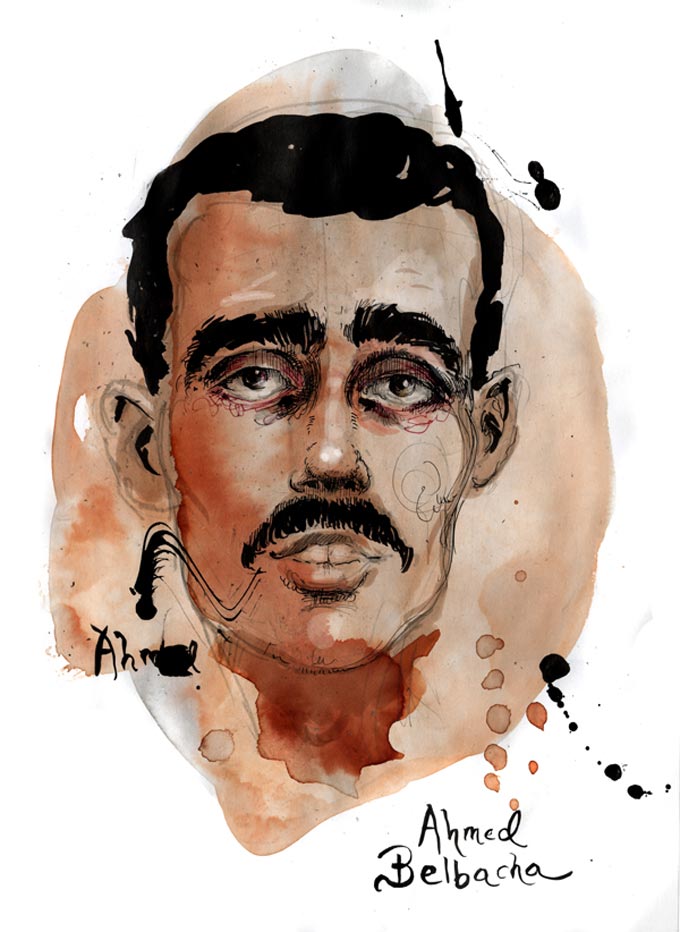

Ahmed Belbacha

Molly Crabapple, Ahmed Belbacha, 2013.

A former civil servant, Belbacha fled his native Algeria after receiving death threats from the fundamentalist guerrillas of the Groupe Islamique Armée. He settled in England, where he worked as a cleaner. Belbacha once cleaned the rooms of Deputy Prime Minister John Prescott. He got a nice tip. But Belbacha’s asylum application was turned down and, fearing deportation, he left for Pakistan and then Afghanistan. When war hit, he was captured trying escape back into Pakistan.

Cleared for release since 2007, Belbacha was sentenced to a 20-year-prison sentence in Algeria, seemingly for talking slag about the regime. Unable to return home, and with no other countries willing to take him, Belbacha is trapped in Guantanamo. He has been hunger striking since February.

In October 2007, the United States declined Belbacha’s asylum request, sent from Guantanamo’s Camp Delta. The letter states that asylum requests must be filed on U.S. soil.

This piece, commissioned by Creative Time Reports, has also been published by The Daily Beast.