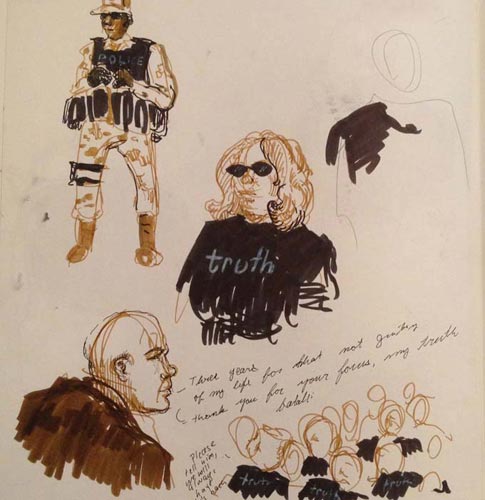

Molly Crabapple, Bradley Manning Supporters, 2013

On a delicious July afternoon, Private Bradley Manning sat in a Fort Meade courtroom and waited to learn if he’d be declared guilty of treason.

No matter how skilled his defense, Manning would be found guilty. He would spend his life in jail.

By handing hundreds of thousands of diplomatic cables over to Wikileaks, Manning revealed drone strikes, civilian deaths and the torture of Guantanamo detainees. In return, the U.S. government charged him with espionage and aiding the enemy. On July 30, Manning’s trial lurched to its inevitable conclusion. No matter how skilled his defense, he would be found guilty. He would spend his life in jail.

The most important whistleblower of the century stood accused of treason. But the trial’s environs had none of the grandeur of Manning’s revelations. Fort Meade, Maryland, home of the NSA and other defense agencies, is an unlovely suburb with vinyl siding, twee lampposts and trivia night at the bowling lanes. The military court only holds about 50, with overflow trailers for the public and the press. Misdemeanor court has more mystique.

Only the guards hinted that the proceedings were special. They carried enough ammo to turn every Manning supporter present into a fine red mist.

Molly Crabapple, Standing Guard in the Courtroom, 2013

I was in Fort Meade to draw. It was not the first time I had drawn a young computer expert facing jail. In March, I had watched court security officers bash Andrew “Weev” Auernheimer’s head into a table during his sentencing for a hacking crime. As the prosecutors argued that he should spend years in a cage, it became clear that his punishment wasn’t about him at all. It was a strike against the future.

The trials of Auernheimer, hacktivist Jeremy Hammond and Anonymous-affiliated journalist Barrett Brown represent the old world fighting back against the new. Their verdicts determine whether we will embrace technology’s possibilities for truth and egalitarianism—or whether we will retreat behind violence and bureaucracy.

The future was in the defendant’s chair along with Bradley Manning. Not that the media noticed. On the morning of Manning’s verdict, CNN brought in experts to discuss Anthony Weiner’s latest infelicities. The major cable networks devoted about five minutes apiece to Manning.

The supporters come because they believe in truth and freedom, but also because they

believe in Manning.

Manning’s supporters recognize why the trial deserves so much more attention. They wear black t-shirts that read “truth.” In the trial’s early days, supporters were banned for wearing clothing with Manning’s face (courts forbid any apparel that conveys an opinion). But the “truth” t-shirts were ambiguous enough to make it past censors. On one occasion, the judge forced supporters to turn their shirts inside out. But the irony felt too heavy. The next day, she allowed the word “truth” to remain legible, undistorted, to the small but devoted public witnessing a trial where the very ability to share the truth about America’s wars was at stake.

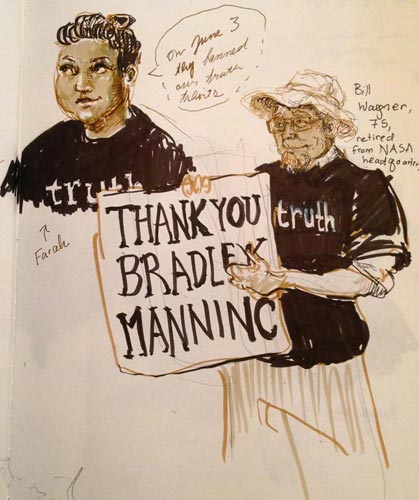

A few dozen pro-Manning protesters held vigil outside Fort Meade’s main gate. Their signs were as hopeful as their smiles, and they were a diverse bunch. Nurses and hard-faced men with cyborg-esque prosthetic legs. Teenagers. Grandmothers in lace blouses. Some older protesters had been coming three times a week, every week, since 2011, when Manning was still locked up naked in the brig at Quantico.

Bill Wagner, 74, is a retired NASA scientist who has been protesting in support of Manning for two years. I asked him why, despite knowing Manning would likely be declared guilty, he’s still here. Wagner told me, “He’s doing such an important job. It just makes me feel like I need to be there. He’s done no harm to anyone and so much good.”

Molly Crabapple, Thank you Bradley Manning, 2013

The supporters come because they believe in truth and freedom, but also because they believe in Manning. Though the judge forbade Manning from so much as looking at them, they spoke of him as a friend. One veteran, whom you wouldn’t want to cross in a bar fight, introduced me to a friend of his who was kept awake by nightmares about Manning. His friend then gave me his badge so I could draw in court, though it had meant everything for him to be there. He told me to draw good pictures. I tried.

Protesters sweltered in the July heat to show Manning he was not alone, even as people driving by called them traitors. “Fry him,” screamed a man leaving the base. A protester flashed him a peace sign. I looked down. Purple flowers came up through the grass. I wondered if they had grass in military prison.

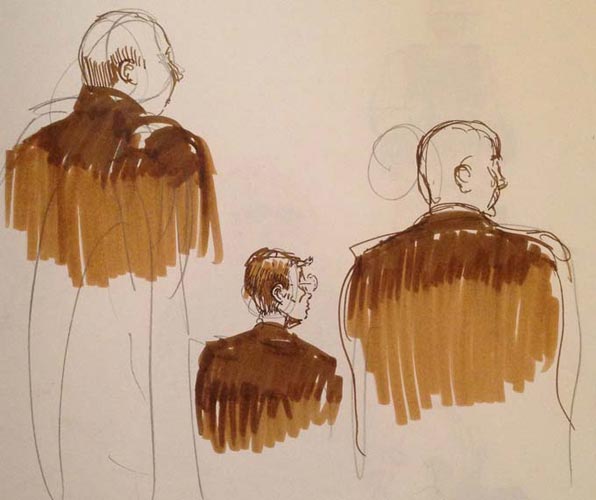

We crowded into the courtroom. There, dwarfed by his lawyers, sat the most important whistleblower in U.S. history. Only 25 years old, Manning stands five-foot-nothing, with razor cheekbones. I’ve never heard his voice, but journalist Alexa O’Brien described it to me as an earnest Oklahoma drawl.

Manning’s supporters could stay forever, but short of a presidential pardon, there is no way for him to walk free.

During the trial, prosecutors argued that Manning had released those cables not as a whistleblower but as a wannabe celeb. In his closing statements, the lead prosecutor showed the court a selfie Manning took after leaking the cables, in which the whistleblower wore a bra. His smile, the prosecutor argued, revealed the face of someone who thought he’d become famous. But the smile Manning wore with that bra might just be the animated expression of someone trying out his true self.

The judge read the verdict. Manning had been charged with aiding the enemy, on the logic that if Osama bin Laden read those cables, whether in Wikileaks or the New York Times, it would damage U.S. interests. It was another battle in the government’s war on the press. The judge found him not guilty of aiding the enemy.

Molly Crabapple, Inside the Courtroom, 2013

Manning smiled a small smile at his attorney, David Coombs. Then the judge found Manning guilty of six counts of espionage. He faces up to 136 years in prison for a total of twenty charges against him.

Reading the verdict took four minutes—four minutes to dispose of a human life. Manning’s supporters sat there dazed. Moments later, the soldiers kicked us out.

Outside, Coombs told Manning’s supporters, “Thank you, my truth battalion.” These people have sat in a mostly empty courtroom, week after week, year after year, to prove that even if the world had mostly forgotten Bradley Manning, they hadn’t. Sentencing would begin the next day. Coombs promised to get back to work. As he walked away, an older woman pressed a coin, engraved with the word “peace,” into his hand.

Last night, Manning’s supporters marched on the White House. In a way, the verdict was the best they could reasonably have hoped for, since the “aiding the enemy” charge was rejected. But it still ends with an idealistic young person locked up for life. Manning’s supporters will stay for the sentencing phase, which may last for weeks. They will stay for appeals, which may take years. They could stay forever, but short of a presidential pardon, there is no way for Bradley Manning to walk free.

In Greece, anarchists spray-painted “Fuck Heroes, Fight Now” on the statue of a general. The media loves to argue whether Manning is a hero or a traitor, but that is beside the point. Heroes and traitors are archetypes. Manning’s a poor kid from Oklahoma who loves Lady Gaga, got into fights and flirted with a hacker who would betray him. He’s a human who did a heroic thing. In that mostly empty courtroom at Fort Meade, other humans do the work of caring for one another, while waiting for the world to notice.

This piece, commissioned by Creative Time Reports, has also been published by The Guardian.