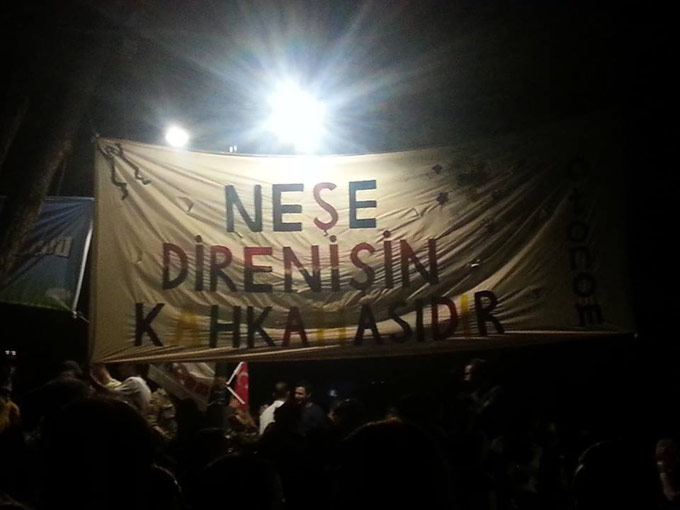

Protesters in Istanbul’s Gezi Park hold a banner that reads, “Joy is the laughter of resistance.” Photo by Defne Ayas, June 3, 2013.

Early in June, as demonstrations spread throughout Turkey following the repression of protests in Istanbul’s Gezi Park, Creative Time chief curator Nato Thompson emailed Turkish curator Defne Ayas about the upheaval. Ayas, who is now Director of Witte de With Center for Contemporary Art in Rotterdam, has organized several landmark projects aimed at bringing provocative art and performance into the public sphere. The conversation below tracks the unpredictable momentum of the uprising, and its many connections—both social and aesthetic—to the art world.

Nato Thompson: I am sure that the protests that originated in Istanbul and spread throughout the country, like many social movements, came about through a combination of multiple factors. What are your thoughts regarding the causes of such widespread action?

Defne Ayas: The spectrum of disappointment voiced near Taksim Square, and in centers of protest across the country, has been quite wide. What you are seeing is a chain reaction to the Justice and Development Party (AKP)’s increasingly authoritarian turn, and—in the case of Gezi Park—to Prime Minister Tayyip Erdogan’s self-appointed mandate to cipher the whole city with his own visual codes and aesthetics. The AKP’s top-down urbanism, seen in Erdogan’s master plans for a neo-Ottoman revival, was the impetus for the Gezi Park protests. Another, more general issue is that each time this government assures citizens it is initiating administrative and judicial investigations following murders, massacres or bombings, for instance, nothing much happens. Not a single resignation ever takes place. Just now, the police officer who shot and killed protester Ethem Sarısülük was released by the court on the grounds that he was acting in self-defense. This lack of accountability has become unbearable for the people.

While a number of protesters would acknowledge the AKP’s several successful initiatives, many have been angered about its clamping down on opposition voices in the press and media as well as amid minority groups. Some have been worried about the government’s ongoing campaign to demilitarize Turkish politics, since they have seen the military as the so-called guardian of Turkish democracy, against political Islam, Communism and so forth. Meanwhile, Erdogan’s support for legislation to ban abortion from four weeks after conception on—the current law allows abortion up to 10 weeks after—did not sit well with women, to say the least. And the government’s meddling into the lipstick choice of Turkish Airlines crew members was the cherry on top.

Riot police in Turkey, after women angry about changes to abortion law pelted them with eggs. Screenshot of Beyaz Gazete video courtesy of Defne Ayas, June 24, 2013.

Many secular families of Turkey have increasingly come to experience the gradual ceding of their sociopolitical and economic ground to those of religious conviction. Deep down, secular people are concerned that the increasing expansion of the new Islamic middle class may come at the cost of their own freedom.

NT: I know that there were plans to remove Gezi Park to make way for a strip mall. Can you provide any more background on this battle against gentrification and the ways in which it is shaping the question of how the city of Istanbul is lived in?

DA:The Prime Minister, who was himself imprisoned back in the day for reciting Islamic poetry, recently lashed out against secular citizens’ “elitist” take on art, architecture, cinema and poetry, which he thinks is all Western-flavored. The development of Gezi Park has long been on Erdogan’s agenda, ever since he was mayor of Istanbul, in 1994. And many prior mayors and prime ministers wanted to revitalize the square, which is prime real estate—a developer’s dream location.

The AKP’s development plans reveal a rush to seal and institutionalize its decade-long political legacy.

Erdogan not only proposed an alternative Gezi Park that would turn it into a shopping mecca for the rising Islamic middle class and remove any possible architectural setting for peaceful protests, but he is also planning a second canal, a third bridge to travel between Asia and Europe and a gargantuan mosque along the Bosphorus, on the Çamlıca hill. The concert hall/exhibition center that he built along the Golden Horn is an awful representation of his marble-and-brass-loving aesthetics, built as if Istanbul were a third-tier city in China. The AKP’s development plans reveal a rush to seal and institutionalize its decade-long political legacy.

NT: It is probably also good to look at the history of the square to understand the dynamics of the events.

DA: Taksim has always been a politically charged square, especially in its role of hosting the annual May 1 protests. I’ll spare you that long history; today, many would agree that Taksim is one of Istanbul’s least attractive squares, and that it needs healing and re-envisioning. That said, it has symbolic potency for Turkey. The square is the entry point to Istiklal Caddesi, a street that was a popular spot for Ottoman intellectuals and Italian and French Levantines in the 19th century. Currently a pedestrian-only shopping street, it is also home to several contemporary art spaces and galleries.

A transgender pride march along Istanbul’s Istiklal Caddesi. Found photo courtesy of Defne Ayas, 2013.

On the other hand, the square features the prominent Taksim Republic Monument, erected in 1928 to commemorate the formation of the Turkish Republic; the Ataturk Cultural Center (AKM), which used to host many productions of the Turkish State Opera and Ballet, catering directly to the tastes of the republican elite, and which forms a modernist focal point in the square; a tall hotel with a buzzing café underneath, attended by locals and tourists alike, and an adjacent Starbucks that popped up recently; a subway station built by the current government; and a distasteful parking lot for public buses in front of the hotel.

Gezi Park is across from the hotel, next to the square, diagonal to AKM, and set upon an Armenian cemetery that was used for centuries. The cemetery had encompassed most of the areas surrounding the square, on whose parts various hotels and the state radio building were eventually raised. In the 1930s, the graveyard was confiscated and demolished. The Taksim military barracks on the other hand, with all of its historical encryptions, which the prime minister wants to revive, was also located here.

NT: Who do you see participating in these events and what agendas do you think they have?

DA: I was only there for nine days, and I have had to follow the rest online and via my friends. This much I can say: each group stands with its own agenda, but all are united, at the moment, for the cause. Archrival football fans came together in one group. LGBTQ rights advocates have been there from day one, as well as DISK, the workers’ union. DISK also called for a general strike across the country on June 17. It is not at all a “white secular Turk” movement; Kurds and anti-capitalist Muslims have also been present in the park. Gezi Park comprises a sound group of people, super-resistant to external manipulation and capable of seeing through all provocations. This will surely change with time, as questions arise about organizational issues and external forces try to meddle with the movement.

It is not at all a “white secular Turk” movement; Kurds and anti-capitalist Muslims have also been present.

NT: Can you talk a little bit about the fight for Taksim Square itself? I’m interested in the spatial dimensions of these events as well.

DA: In Istanbul, it seemed as if the protest had three focal points within the same area: the sit-in at Gezi Park, the activities in Taksim Square and the propaganda banners on the AKM. The park played host to architects, filmmakers, students, feminists, cooks, doctors, urban gardeners, musicians and performers. It felt more like a concert crowd. Music was composed, performed and recorded during the sit-in—including the now-famous, symbolic piano concerto. Meanwhile, the facade of the AKM was covered with banners from more or less defunct leftist organizations, and Soviet Generals Vesilyevic and Frunze of the Taksim Republic Monument were dressed up with banners displaying outdated jargon from still-active leftist groups. In front of the monument, a corner was reserved for anti-capitalist Muslims, who prayed daily.

One thing that struck me in the first 18 days was the absence of isolated “artists’ corners.” No such hierarchies were formed; that was the beauty of the park. It was flamboyant, with jokes, graffiti and banners on view everywhere. Creativity and a sense of humor were the main threads running through all the groups in the park.

NT: How do these events in the park connect with the artist communities working in Turkey?

DA: Historically, issues of power, identity, gentrification and cultural heritage have always been on the radar for artists in Turkey. This is not new. But Turkey is currently going through a phase where anyone who has criticized the government is immediately disfavored. Now that the media has been systematically dismantled, the art world feels it has to work harder to raise awareness and disseminate news about political causes, and it has many channels available to that end. However, today’s protests are not the first cause to unite artists in recent times. Rather, the first one I witnessed was the murder of Armenian-Turkish journalist Hrant Dink, in 2007.

It is also important that to note that the international art world has stood by the protesters in Turkey. You could see this at the Venice Biennale on June 1, when about 100 artists and art professionals came together to protest, or on Facebook, where the Romanian artist Dan Perjovschi has regularly been posting caricatures in solidarity, or via e-flux, Art-Agenda or Metropolis M, which have circulated nuanced takes on the uprising.

Artists and art professionals stand in solidarity with protesters in Turkey, outside the Arsenale at the Venice Biennale. Photo by Defne Ayas, 2013.

Life has fulfilled the promise of the 2013 Istanbul Biennial’s premise, ahead of time.

NT: How do you imagine this will affect the upcoming biennial curated by Fulya Erdemci, for example?

DA: We should ask her. In my opinion, life has fulfilled the promise of the 2013 Istanbul Biennial’s premise—to examine “the notion of the public domain as a political forum”—ahead of time. Also, the biennial’s main sponsor, Koç Holding, which has been a target for protesters in past years and as recently as a May 10 biennial event, is now supporting the protests. Not directly perhaps, but it was one of the more generous corporations, opening its conglomerate’s hospital and luxury hotel to the protesters in nearby Taksim. (The charitable act had little effect; police gassed protesters within the hotel.)

After witnessing Gezi Park, South African artist Kendell Geers called the park a giant installation and ongoing performance piece staged collectively by the public, with no overarching curator or director. Geers questioned the need to stage the Istanbul Biennial. I have no doubt that Fulya Erdemci will use the biennial as a platform to discuss it all and bring many daring artists to the city this fall.

Demonstrators perform a “stand-in,” a new form of protest discussed below, in Istanbul. Found photo courtesy of Defne Ayas, 2013.

NT: What kinds of shifts do you expect in the long run? How do you imagine this playing out in people’s minds?

DA: If Turkey cannot reconcile its secularism with its rising set of Islamic values within a democratic model, this has wide political and economic consequences for the rest of the world. Events here should be followed closely, collectively, with a persistent demand for justice, with respect to all our causes and within a rising populist discourse across the globe. Gravity is definitely now in the Middle East-China axis. This is not a story for Turkey only; its ripple effects will most likely be felt across Europe, in the United States, Mongolia, Vietnam, Senegal, you name it.

Some urgent questions are: Is an Islam-tinted government possible within a democratic framework? To what extent have the AKP’s support networks already expanded globally? How will the European Union conduct negotiations with Turkey about its potential entry into the Union? Will it see the protests as an excuse not to admit the nation into the EU?

This is not just Turkey’s story; its ripple effects will be felt across Europe, in the United States, Mongolia, Vietnam, Senegal…

And on a lighter note, who will stage better and more spirited protests than those from Turkey?

NT: Since our interview began three weeks ago, the government has squashed the demonstrations in the square with tanks, water cannons and batons—a surprise eviction that seems all too familiar from here in New York. What is the state of things at this point?

DA: It was not until the 17th day of the protests that Erdogan’s office invited the Taksim Solidarity platform and select celebrities for a so-called consultation. Meanwhile, Ankara was burning. If, at first, we wondered whether the meetings were well-intentioned or a mere PR move, we soon saw that they were purely cosmetic: on June 15, the government cracked down on protesters again and wiped Taksim Square clear of people using tear gas and water cannons.

CNN footage of a consultation, initiated by Erdogan on the 17th day of protests, which included entertainment celebrities. Screenshot courtesy of Defne Ayas, June 13, 2013.

Following Erdogan’s consultation with a select group of activists, protesters meet to discuss what to do next, in Istanbul’s Abbasaga Park. Found photo courtesy of Defne Ayas, June 13, 2013.

Soon after, about 1,000 people spontaneously gathered in Istanbul’s Abbasaga Park for a public forum on “what to do next.” One man stood in Taksim for several hours, an act that resonated with the art-world craze for “the medium of protests” and critic Kaelen Wilson-Goldie’s recent Artforum piece on the Venice Biennale, “Bodies that Matter.” He was soon cloned by scores of other protesters; the sit-in became a stand-in. We know now that this was an artist, Erdem Gunduz, who became a symbol of peaceful protest in Taksim Square, inspiring a movement and a hashtag: #duranadam.

Today, as the unrest has continued and the most intense protests have shifted from Istanbul to Ankara, over a thousand—and potentially many more—protesters have been detained and accused of being part of a larger crime network. The government has started a witch hunt, labeling doctors who helped the wounded and lawyers who filed petitions on behalf of protesters its enemies. Activists using Twitter are closely watched and threatened, and the interior minister has proposed a bill that would give the national intelligence agency far-reaching powers to monitor citizens—according to The Economist, reporting on the bill has been banned in Turkey. I would not have known about it if I were only following national media.

More and more forums and working groups are in the midst of meetings at the moment. Protesters have set up urban guerrilla parks. Artists have taken the initiative to gather and discuss what forms of activism they can undertake together. It is only the beginning.

All opinions stated here are those of the author and do not represent the organizations with which she works.