Protesters gather in Gezi Park. Photo by Can Altay, Istanbul, 2013.

Istanbul and many cities across Turkey have witnessed a widespread insurgency over the last two weeks. Gezi Park, a green area next to the central Taksim Square, has been the site and springboard of this resistance. The park has become simultaneously a symbol for the uprising and a utopian public space, revealing an explicitly urban politics that does not register with existing political factions or discourses.

Background: Construction Time (Again and Again)

The heavy-handed re-development plans set forth by Prime Minister Tayyip Erdogan and his Justice and Development Party (AKP) began in Istanbul’s periphery. This periphery is both geographical and social; it includes the outskirts of the city as well as very central neighborhoods inhabited by the socially peripheral, such as the Roma community of the Sulukule area. The government’s plans manifested themselves in forced evictions, and in the destruction of existing houses to make way for new ones. Of course, the new housing was hardly fit for the previous tenants. Or, to use the language of neoliberalism, the tenants were not fit for the housing. Either way, the new apartments were clearly erected for a wealthier bunch, and lower-income people were pushed further to the peripheries.

When it was adopted by the governing AKP, the Housing Development Authority (TOKI) turned into an organ of the Office of Prime Ministry, adopting the latter’s agenda of widespread reconstruction. (Meanwhile, the former director of TOKI is now the Minister of Environment and Urbanism, further centralizing the process of redevelopment.) Under Erdogan, TOKI steered away from its ideals of providing affordable housing, adopting the role of a neoliberal motor for the entire construction industry. And so the search for valuable land to be grabbed and developed continues, both on the outskirts of Istanbul, within the city and all around the country.

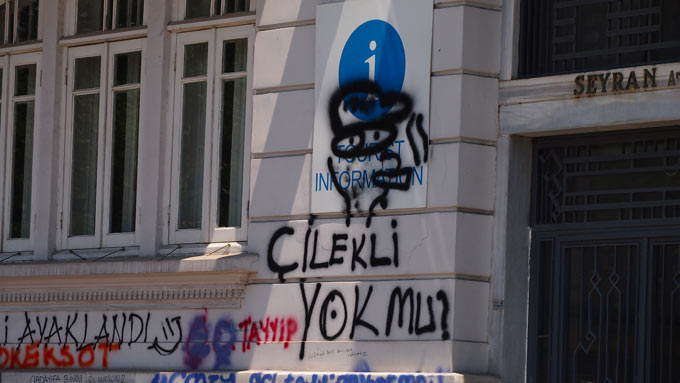

“Do you have this in strawberry flavor?” reads a protester’s graffiti, a tongue-in-cheek response to the police’s use of pepper gas. Photo by Can Altay, Istanbul, 2013.

Trigger: Police Brutality over Public Space

It is important to remember what spawned the resistance. A small group of protesters was heavily attacked for defending a few trees in the Taksim Square redevelopment construction site, which also includes the now famous Gezi Park. Footage clearly shows the police defending the contractors and their bulldozers, and not the citizens or the inhabitants who wanted to express their discontent.

The prime minister declared his decision regarding the Gezi Park once more. A perfect portrait of the ruling ideology was to be built—a moneymaking machine masquerading as a faux-historical landmark. Yes, the authorities were making way for a shopping mall (or a high-end residence, or a hotel) that would look like an Ottoman-era military barracks, to replace a “useless”—that is, non-income-generating—patch of greenery.

What’s happening at Gezi and beyond makes us reconsider the limits we have lived by until now and to imagine otherwise.

The police brutality toward a handful of activists who wanted to save the trees led more and more protesters to join the struggle. In turn, the increasing number of people in the park and on the streets incited more extreme violence from the police. And so the events spiraled into an urgent situation. The government’s usual paternalistic tone, insinuating, “We know what’s best for you,” did not help, either. Thanks to Erdogan’s stern response, and the continuing police brutality, discontent finally found its release in protests that spread far beyond Istanbul, to cities like Izmir and my hometown, Ankara, and were no longer about Gezi Park.

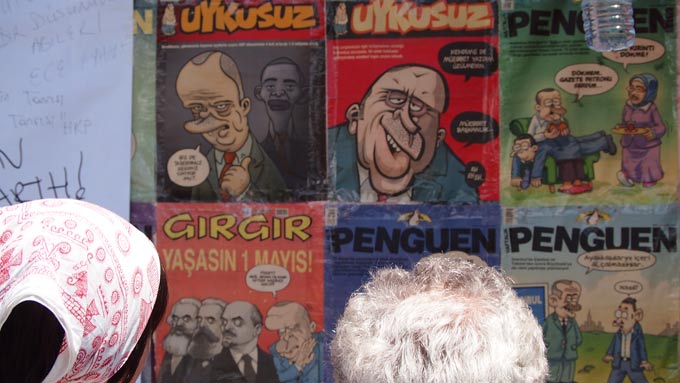

Covers of humor magazines are displayed in a makeshift “revolution museum” between Taksim Square and Gezi Park. Photo by Can Altay, Istanbul, 2013.

Critical Humor and Social Media

For a long time, and increasingly under the AKP government, humor magazines have served as the only outlets for open political criticism. Despite lawsuits and threats, satirical publications like Uykusuz and Penguen, which follow in the tradition of cartoon journals like Girgir, Limon and Leman, have continually mocked corrupt politicians and unjust policies, providing a wide readership with news that no mainstream media dared to touch. The relentless sense of humor that characterizes this resistance has been, in my opinion, largely fed from this genre of journals.

CNN Türk opted to air documentaries about penguins during the hottest hours of the resistance.

Social media’s role in the uprising is also undeniable, not only in terms of communication but also in the way it helps lift the spirit. No wonder the prime minister called Twitter “a menace to society.” In effect, these alternative media—humor magazines and social media—bring together an engaged, critical public, separate from the sort that mainstream news channels try to construct. To give you an idea of the mainstream media here, CNN Türk opted to air documentaries about penguins during the hottest hours of the resistance. Such ludicrous attempts at censorship got what they deserved on the satirical front. Images of penguins with gas masks joined the caravan of caricatures lampooning power in all its manifestations. Humorous messages and cartoons spread through the web came together with defiant slogans on the streets to create a hybrid public space of resistance, both offline and online.

Images of the protests are displayed inside the “revolution museum.” Photo by Can Altay, Istanbul, 2013.

Things Will Never Be the Same Again

Public space is full of limits. The police were called in to declare, “You have no say over how this space is formed.” But the protesters showed otherwise. A limit has been passed; that much is certain. Some call it the “fear barrier.” At Gezi Park people hail from many factions and tendencies. There are those who identify themselves with a political position, and those who, save for their attachment to green space or discontent with the general situation, do not. They were all there. We were all there: first in the park, then, after the police kicked us out, on the streets, and now back at the park and all over Taksim Square. This is the power of presence, of being there, and having your say.

Public space should no longer be male space.

Taksim Hepimizin! The public space of Taksim belongs to all of us, not some of us. Public space should no longer be male space. The presence of women and LGBTQ people, who are subjected to violence everyday, is less and less tolerated in public space. The prime minister’s appetite for social engineering contributes to this environment of discrimination, with his declarations celebrating motherhood (with a minimum of three kids) and sobriety. Yet, at Gezi, women and queer people are present, perhaps more than ever, in making public space truly public.

A garden planted by occupiers at the demolished edge of Gezi Park includes peppers, a salute to the widespread use of pepper gas by police. Photo by Can Altay, Istanbul, 2013.

Imposed limits have now been transgressed; people realized that only the public makes public space truly public. This recognition brought solidarity and joy to the park, where it flourishes, with only minor hiccups like the occasional shortage of supplies, bouts of rain and the unease of waiting for something worse to happen. There is now a beautiful garden with vegetables, including peppers, an homage to the pepper spray employed by police, and new trees. We have an open library, free lectures and forums for conversation. Even though nothing is free outside of the park, there is no currency inside; food and medicine are provided by the public for the public. The park is like an open book; texts and quotes abound. It is a learning experience for everyone.

As such, Gezi Park is reminiscent of anarchist and writer Hakim Bey’s concept of the “Temporary Autonomous Zone,” an ideal of a claimed territory without rulers. The park is now a tent-ville, an impromptu commune whose members care about producing and sharing knowledge, and worry about sustainability.

Protesters have erected tents, asserting their presence in public space. Photo by Can Altay, Istanbul, 2013.

Finally, It Has Happened to Me

The events revealed a potential, and resulted in a mobilization, I have never seen in my life. I finally got a glimpse of another sense of the word “public” that went beyond the categorizations that kept people apart for so many years.

Humor and the reinvention of public space are the two best lessons to take home from this resistance, not only in Turkey, but all around the world. I will not claim that these events constitute art, nor am I generally inclined to see activism as art or art as activism. However, what’s taking place is certainly artistic activity. Artists take models, make models and reflect on existing situations, offering possibilities for how to think about or see the world differently. What’s happening at Gezi and beyond makes us think, question and reconsider the limits we have lived by until now and to imagine otherwise.

Imagination expands slowly and strikes suddenly.

I have probably laughed more within these past two weeks—not to mention, cried a little—than I have in any given year. I believe the outburst of such humor, and the possibilities for reimagining public space, has been indirectly fed by comics, literature, art, cinema and music for many years. Finally I get it: imagination expands slowly and strikes suddenly.

Postscript

Everybody keeps asking what is to come, what will happen and where this will all lead. I do not have an answer. Everything is changing on a daily basis, and we will soon see what comes of the recent talks between protesters and Erdogan. But it’s important to recognize that the people of Turkey have been triggered to imagine otherwise and invent anew. The spirit of humor, creativity and critique should continue in a network of places both peripheral and central. As a result, hierarchies will keep dissolving, and the “inhabitants”—of this country, of this political system—will finally claim the power to have a say in how their lives are formed—collectively and continuously.

This piece, commissioned by Creative Time Reports, has also been published by Ibraaz.