The Heidelberg Project’s Obstruction of Justice House, devastated by a fire on May 3, 2013. Photo by Trista Dymond, May 6, 2013.

On May 3 we received a series of phone calls informing us that the Obstruction of Justice House, one of the Heidelberg Project’s major monuments, was on fire. Even though the project has been partially destroyed twice before, in 1991 and in 1999, each time by order of the city government, the blaze came as a complete shock. I got there about 8:30 a.m. and the Detroit Fire Department was carefully trying to contain the fire without harming the installation. Heidelberg’s founder, Tyree Guyton, was already there when I arrived. He watched, he listened and he consoled people. He said, “We’re going to turn this into something positive. We’re going to find a way to make this work.” But the house is pretty much no more.

The Obstruction of Justice (O.J.) House on Heidelberg Street came about in 1994, after a family moved out of the structure, gave the keys to Tyree and said, “Turn it into a work of art.” The O.J. House referenced the project’s struggles with the city of Detroit: after the 1991 demolition, we often discussed how the city’s actions were an “obstruction of justice.”

The Heidelberg Project’s Obstruction of Justice House. Photo by Elayne Gross, 2010.

As the 1990s progressed, so did the facade of the O.J. House. It came to encompass everything that was going on in our society, including the O.J. Simpson trial—which, although important, didn’t warrant the type of media hype it received. Once, the structure was completely covered in an off-white liquid latex material as part of a collaborative experiment with architects; the house became a great backdrop for screening movies for the community. In 2004, we wrapped the entire structure in a giant American flag.

People came from all over the world to see each new installation. In this respect, the Heidelberg Project is no different than a museum. And the O.J. House, which had been the oldest part of the project since the demolition of 1999, was a very symbolic structure until it burned down.

The Heidelberg Project’s Obstruction of Justice House, devastated by a fire on May 3, 2013. Photo by Trista Dymond, May 6, 2013.

Heidelberg’s previous demolitions were politically motivated, whereas this fire—which turned out to be an act of retaliation by a youth in the community—was not. In 1998 we went before the Detroit City Council, which wanted the Heidelberg Project gone and threatened to have it removed. But we filed a restraining order to stop the Council and ended up in court. We prevailed in terms of continuing this public art project, but we lost the damages claim, which resulted in a second demolition because part of the project was on city-owned land.

People have had mixed feelings about the project for a long time, particularly in the African-American community where it is situated. One councilperson said, “This is not done here. You take that to New York or Chicago.” That gives you an idea of what we have been up against. Many politicians and citizens could not see the value in the Heidelberg Project. On the other hand, universities, artists and visionaries held us up as an exploratory new concept in urban development and architecture.

The Heidelberg Project’s New White House. Photo by Michelle Figurski, 2012.

Tyree is a pioneer. He wasn’t satisfied painting on canvas. He attended Detroit’s College for Creative Studies (CCS) in the mid-1980s, but he was told that his style “did not fit” and consequently he quit. In 1986 he had an epiphany: he saw how he could transfer his art from the canvas to the street he grew up on, as a way of making a statement and helping people see beyond what they thought was trash and debris. It raised so many questions and inspired a lot of people. It’s one of the reasons there are so many community art projects and public installations around the country today, including Rick Lowe’s Project Row Houses in Houston. Ironically, in 2009, CCS awarded Tyree an honorary doctorate in fine arts.

Although many outside Detroit extolled the Heidelberg Project, and Tyree received major accolades including an Emmy Award for the documentary Come Unto Me: The Faces of Tyree Guyton, the city of Detroit remained silent. Foundations were not supporting our work and we struggled to keep our heads above water. The economic meltdown and automotive industry collapse in 2008 hit Detroit hard. Cars have been the lifeblood of the city for a hundred years, and in an instant, the industry seemed to be no more. Yet it was amid all of the city’s problems that we received our first substantial grant in 2009. The economic crisis pushed our work to the forefront.

Detroit is home to people who have never lived anywhere else, especially African-Americans who came here from the South looking for jobs. Now, people are losing jobs and leaving the city rapidly. We’re down to a population of 700,000. At the same time, we’re also getting an influx of young people because they can literally create a life for themselves in this city right now. There’s an amazing art movement, lots of farming, surplus land and small businesses. We’re seeing a resurgence of hope among everyday people.

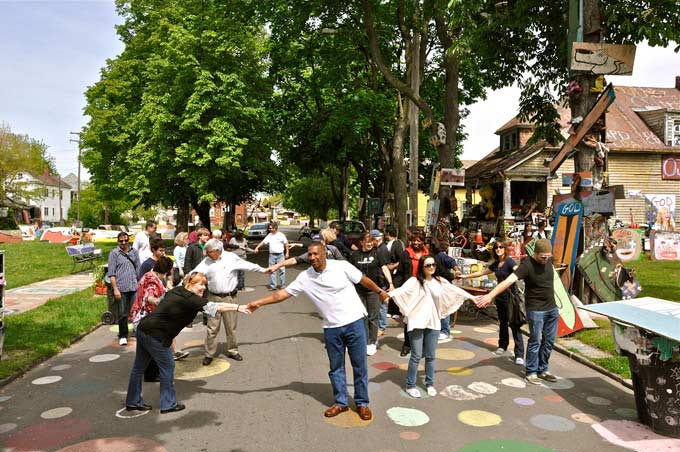

Heidelberg Project founder Tyree Guyton connects with visitors on Heidelberg Street. Photo by Geronimo Patton, 2010.

When Tyree started the project in 1986, it was a forewarning; he was already looking ahead at what was possible for the city. Today, people in the community ask themselves, “If this man can do what he did, what is possible for me?” That in and of itself is pretty powerful. We also have a new generation of people who grew up in school learning about Tyree. This generation of young people is asking smarter questions. Young people are concerned about the future of this country and they want to help. For this group, the Heidelberg Project represents new possibilities; these young people have helped us to educate many of the people who previously resisted the project. Many artists now credit Tyree, who introduced a novel art form to the city, for paving the way for today’s new art movement in Detroit.

By building an outdoor museum in the heart of an urban community, the Heidelberg Project restored a sense of hope to a large number of Detroit’s residents while helping them to understand that it’s going to take all kinds of people to keep this project, and this city, vital. We believe the Heidelberg Project will jump-start a new paradigm, where art becomes a catalyst for positive change, economic development and racial integration. It’s already happening and it’s phenomenal to watch.

Statement by Jenenne Whitfield, executive director of The Heidelberg Project. This piece, commissioned by Creative Time Reports, has also been published by Blouin ArtInfo.