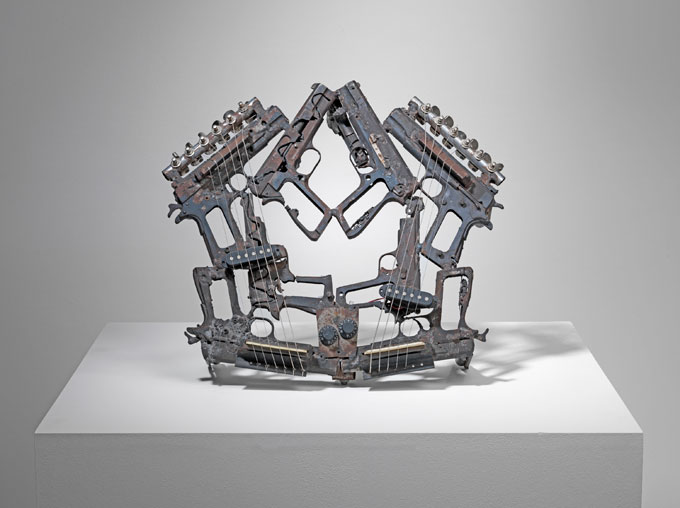

Pedro Reyes, Imagine (Double Psaltery), 2013. Courtesy of the artist and Lisson Gallery, London.

In the wake of the shooting at Sandy Hook Elementary School in Connecticut that killed twenty children and six adults, gun sales soared across the United States. It is a sadly familiar response in a country where nearly half the population keeps a gun at home (as of 2011). After each massacre, whether a mass shooting in a Colorado movie theater or the attempted assassination of an Arizona congresswoman that killed several bystanders, Americans have bought guns at a higher pace than they did before the rampage.

Lax gun laws in the United States also have devastating effects south of the border: over 250,000 guns are smuggled into Mexico each year, contributing to the country’s warlike conditions. As an urgent debate about gun control continues after regulations aimed at keeping guns out of the hands of criminals were defeated in Congress, we turned to Mexican artist Pedro Reyes, who in two major projects spanning the last several years, has responded to gun violence by transforming weapons into art.

—

In 2007, I was invited to Culiacán, a major drug trafficking center that is also one of Mexico’s most violent cities, to launch a campaign where residents were asked to donate weapons that were then melted and made into shovels to plant trees. We received 1,527 guns, steamrolled them and transformed the metal into 1,527 shovels we used to plant the same number of trees.

Pedro Reyes, Palas por Pistolas, 2007–present. Courtesy of the artist.

Pedro Reyes, Palas por Pistolas, 2007–present. Courtesy of the artist.

Pedro Reyes, Palas por Pistolas, 2007–present. Courtesy of the artist.

This project, Palas por Pistolas, developed in response to a situation that has only gotten worse. Over the last six years, more than 70,000 Mexicans have been killed in drug-related violence. There are now voluntary gun donation campaigns throughout the country. People are eager to clean out the huge number of weapons that Calderón’s presidential term brought. But we can’t stop the flow of guns on our own: we need change within the United States.

As it stands now, the United States is an extremely dangerous neighbor. It’s impossible to buy a weapon in Mexico; there are no armories here. But with such lax gun laws across the border, drug traffickers only need to take a short drive to Walmart or any other of the nearly 7,000 gun retail shops along the U.S.-Mexico border.

To get to the root of the cartel wars, the United States will need to end its War on Drugs.

For my latest project, Disarm, I have taken guns seized by police in Ciudad Juárez and turned them into musical instruments: guitars, drums, marimbas and so on. I think about Disarm as a form of exorcism, expelling a demon that has overtaken the body. In the United States, demons of war and violence possess the social body. There are 89 guns for every 100 citizens in the United States. The country spends more than the next 13 nations combined on its military. You have to defeat and tame the demon before you can expel it. In the instruments I’ve built from guns, the weaponry appears intact—though, of course, it is no longer functional—so that people still have to deal with this demon.

To get to the root of the cartel wars, the United States will need to end its War on Drugs, which has, in my opinion, spawned the violence in Mexico. Hundreds of thousands of Americans are in prison for nonviolent drug offenses. Marijuana has never killed anyone, while a single weapon can kill people for generations, because there’s no planned obsolescence in these objects. A gun manufactured 50 years ago may function as well as it did the day it was made.

Pedro Reyes, Imagine (Psaltery), 2013. Courtesy of the artist and Lisson Gallery, London.

The two big cultural shifts that we have to undertake in this century, I believe, are a new policy toward drugs and a new policy toward guns, which are intrinsically related projects. First, in terms of health, prescription drug abuse causes many more deaths than the use of illegal drugs. Then there are the “side effects” of the War on Drugs, whether mass incarceration or the gun violence that an illicit drug market fuels. For gun companies to thrive, you need conflict. You need fear, you need wars and you need crime. This doesn’t mean that all drugs should be legalized at once, or that all weapons should immediately be banned. But we obviously need a major readjustment. We are living in mayhem.

—

With both Palas Por Pistolas and Disarm, I think about the tradition of alchemy, where, simultaneous with the physical conversion of a substance, a psychological transformation is supposed to occur. As children use former weapons to plant trees, or musicians play instruments that are visibly composed of guns, they engage in a concrete activity that is positive, but also in a ritual that builds trust.

I want to live in a world that is moving toward common trust rather than universal fear.

A cultural rejection of weapons as an industry must come about if we want to see real change in the prevalence of guns. Investing money in a company that makes weapons should be regarded as dirty—a sin. If you are investing in weapons, you are fueling death and suffering around the world. It should be a responsibility for everyone on earth to go on a crusade against guns.

Pedro Reyes, Imagine (Bass Guitar Bass), 2013. Courtesy of the artist and Lisson Gallery, London.

Change will be difficult; even setting aside the economic interests maintaining the status quo, I believe there is a certain amount of violence in our nature that we can’t eliminate. We have to find ways to sublimate that violent energy, like smashing guitars into pieces or shouting into a microphone. If the people who set off bombs or commit school shootings had the opportunity to become artists, maybe they would be doing political art and not bombing!

We have to refocus the rage that exists in society and provide creative outlets for it. As Freud wrote in Civilization and Its Discontents, “The first man who hurled an insult instead of a stone was the founder of civilization.” We will always want to kill each other, but we can find new forms to channel our frustration into some sort of symbolic violence and prevent the emergence of real violence.

When weapons are widespread, you can either push to make them ubiquitous or rare. I believe that you have to organize actions that move in one direction or the other. In the Cold War, the United States and the Soviet Union acquired more and more nuclear weapons to outdo each other. Disarmament remains the harder direction to take. But I want to live in a world that is moving toward common trust rather than universal fear.

Pedro Reyes, “Disarm,” installation shot, 2013. Courtesy of the artist and Lisson Gallery, London.

This piece, commissioned by Creative Time Reports, has also been published by Policy Innovations, an online magazine of the Carnegie Council.