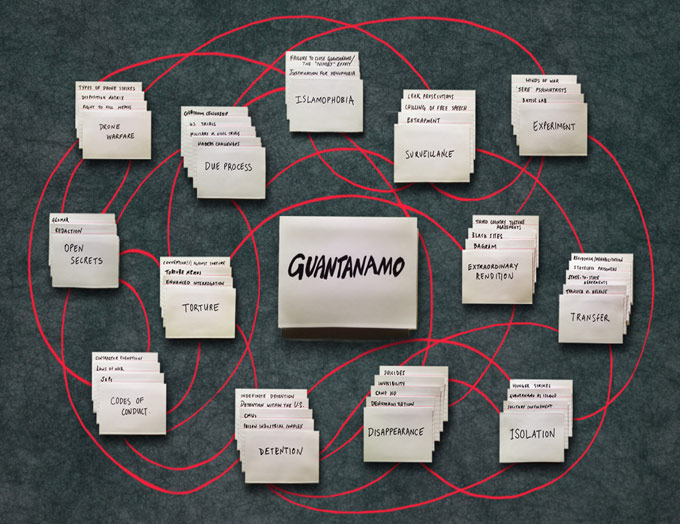

Mariam Ghani and Chitra Ganesh, Screenshot of The Guantanamo Effect, 2013

Scroll to the bottom of the page to navigate the artists’ interactive archive.

The U.S. prison camp at Guantanamo Bay has, over the last 11 years, become much more than a place. In the sphere of U.S. domestic politics, it is an irresolvable problem over which pitched partisan battles have been fought. Its continued existence is a snarl in the larger geopolitical fabric, an irritant that constantly recalls the role of the United States in theorizing and proliferating a state of global war.

At the same time, the camp at Guantanamo and the people imprisoned within it have become bargaining chips used by the United States in structuring its informal state-to-state relationships. For example, in 2005, the United States paid for the construction of a new block of Afghanistan’s Pul-e-Charkhi prison in return for the Afghan government’s agreement to imprison and try detainees transferred from Guantanamo to Afghanistan. Most important, Guantanamo, which originally served the Department of Defense and other government agencies as a “battle lab” where new strategies for the “global war on terror” could be tested, has developed into a set of principles that are now enshrined in U.S. law.

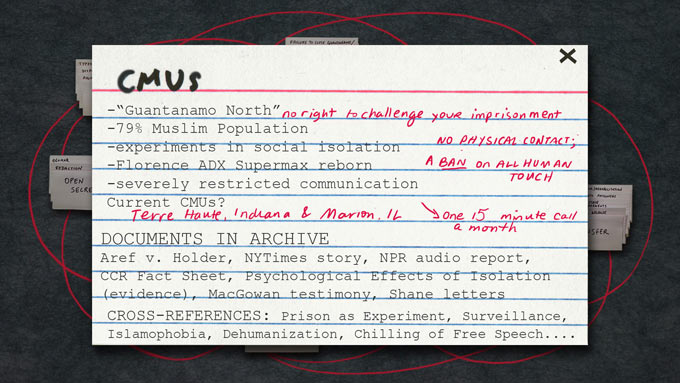

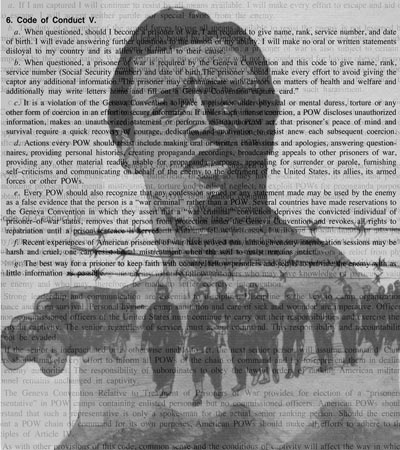

This doctrine visibly surfaces in a now-declassified appendix of the U.S. Army Field Manual on Interrogation (rewritten in 2006 to reflect experiments with new methods at Guantanamo), but remains hidden in the classified JTF-GTMO Standard Operating Procedures that have nonetheless influenced detention operations everywhere from Bagram to Abu Ghraib to the Indiana Supermax prison known half-jokingly as “Guantanamo North.” This emergent code of conduct deploys covert and extralegal surveillance, imprisonment, torture and killing to persistently separate and mark out a particular group of people from the rest of humanity. The Guantanamo code has proliferated like a self-replicating virus in various permutations across the globe, ultimately circling back to spread within our own borders through the tandem expansion of drone strikes and surveillance based on “imminent threat” rationales, and extreme isolation programs in domestic prisons.

Mariam Ghani and Chitra Ganesh, Code of Conduct, 2013

While specific debates over the territory of Guantanamo and the fates of the people still imprisoned there remain urgent, larger discussions of Guantanamo qua policy or politics must admit the broader reach and influence of Guantanamo the idea.

In this commissioned web project for Creative Time Reports, the experimental archive Index of the Disappeared—our collaborative, ongoing exploration of the costs of post-9/11 detention, secrecy and disappearance—provides a portal into some of its current research, centered around Guantanamo as both a reality in place and an idea in circulation. Like the physical archive maintained by Index of the Disappeared, this web project uses idiosyncratic categories and descriptors to trace new relationships between existing documents, and pays close attention to slippages in usage of language and definition of terms as well as omissions, ruptures or oddities in the records. A given strand of research might highlight anything from the assurances against torture proffered by the Ben-Ali and Qaddafi governments in order to secure individual transfer agreements for Tunisian and Libyan detainees, to the link between three reported suicides at Guantanamo in 2006 and an affidavit about “dryboarding” filed at a Charleston naval brig during the same period, to the refusal of Democratic senators to sign a Senate Armed Services Committee report on recidivism.

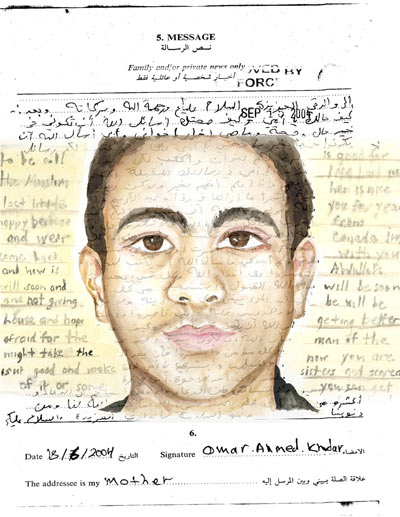

Mariam Ghani and Chitra Ganesh, Transfer (Omar Khadr), 2013

This digital archive has been visualized as a rhizomatic, relational, hyperlinked card catalogue. Each card stack contains one topic card, under which are tabbed subtopic cards. When a topic card is clicked, a related image or image sequence appears (including courtroom drawings, portraits and other images created for the Index, and diagrams from official documents and military field manuals). When a subtopic card is clicked, a detail view of the card appears, revealing a text fragment that has been abstracted from relevant documents in the archive. When the text card is hovered over or clicked, an informational card will appear (if more information is available). Each informational card contains notes on its subject, cross-references to other topics and subtopics and a series of links to relevant items from the Index archive or related online projects: primary source documents, first-person narratives, reports or analysis by third parties and/or audio recordings. The linked information represents a broad cross-section of publicly available archival resources—a mix of the official and the mundane that includes autopsies, affidavits, correspondence, interviews, invoices, legal analysis, media accounts, NGO reports, transcripts, testimony, treaties and more.

Again like the Index’s physical archive, this web project is an open-ended work, which will change from week to week as more resources or layers are added, reflecting the emergence of new information in the context of existing information. We do not pretend to possess a complete understanding of Guantanamo and all of its effects. But we hope to map our present understanding of both the “known knowns” and “known unknowns” that flow in and out of Guantanamo Bay, while gesturing toward what still remains in the realm of “unknown unknowns.”

Clicking on the image below will redirect you to the Index of the Disappeared web project on a separate site. Please enable scripting in your browser preferences while on the site for full functionality. For visitors with older versions of Firefox (18.9 or earlier), we recommend the add-on “PDF.JS” for in-browser PDF viewing.

This piece, commissioned by Creative Time Reports, has also been published by Alternet.