Art has always been a tool for me to claim space, build power and speak out about the injustices that have shaped my social experience in the United States. Growing up in the age of “free trade,” amid an expansion of anti-immigrant policies, led me to develop art about these issues. For nearly a decade, most of my art directly served the immediate, short-term needs of social movement work. Separately, I would spend time developing my own body of work in my studio or collaborating with other artists. For years, these two worlds remained separate. Neither the art-and-culture sector nor the social-justice sector was effectively building models for creative collaboration.

Now, through my creative practice and my coordination of the immigrant rights organization Culture Strike, I aim to bring together these once-separate worlds through what we call “cultural strategy” or “cultural organizing.” I presented my vision for the convergence of art and social justice at a strategy session called “Creative Change: Art, Culture and Immigrant Justice,” hosted by Opportunity Agenda in Los Angeles in March 2013. The text below is an adaptation of my talk.

——

To think about how art shapes politics, we need to look far beyond the next political event to consider how we build up a cultural space. Jeff Chang, a brilliant hip-hop critic and journalist, and one of my collaborators in co-founding Culture Strike, has encouraged us to imagine a wave when we think about political change. Normally, when we envision a wave, we think about a climactic event, but in order to reach the peak, all kinds of forces—many of which you cannot see—need to come together.

Artists are central, not peripheral, to social change.

In the political world, we experience the wave’s peak moments through events like elections or policy wins, but we don’t always recognize the undercurrents and conditions that lead us there. In the world of art and culture, many of us help construct the conditions that lead to this climax. Culture is a space where we can introduce ideas, attach emotions to concrete change and win enthusiasm for our values. Art is where we can change the narrative, because it’s where people can imagine what change looks and feels like.

Abraham Lincoln famously said, “Public sentiment is everything. With public sentiment, nothing can fail; without it, nothing can succeed.” It is essential for us to think about these words in the context of the wave, because artists shift and frame public sentiment as they create the cultural ocean we live in every day. You may attend a rally or vote, but you also read books, listen to music, engage with visual art, turn on the radio and create your identity through culture. Artists are central, not peripheral, to social change. To have the movements that make the wave, you need cultural workers.

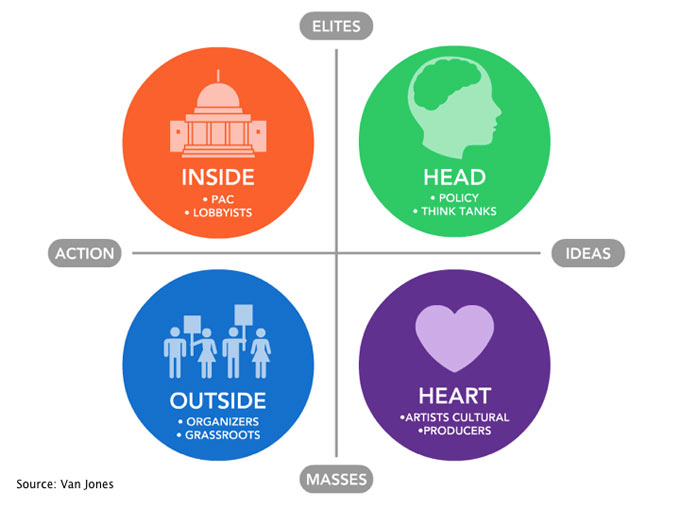

The environmental and human rights activist Van Jones has made an excellent graph mapping the political ecosystem. On the left you have action, and on the right, ideas; elites are at the top, and the masses are below. There’s an inside game and an outside game. On the inside, there’s big money: elites are throwing millions of dollars into political lobbying. The inside game is the force that creates policy. On the outside, we apply tremendous pressure so that our elected officials pass laws that give us power. The Occupy and immigrant rights movements are forceful players in this outside game, making sure that the inside is moving.

The left side, “action,” often means quantifiable policy changes: a bit more funding here, a higher age limit there. The right side, “ideas,” can be harder to see. We are not necessarily talking about concrete things here, but rather, a “head space.” Academic institutions and think tanks, which are not always involved in the immediate policy wins, are significant in creating a culture of thought.

Artists are represented here on the side of ideas, in the “heart space.” Art is uniquely positioned to move people—inspiring them, inciting new questions and provoking curiosity or outrage. Normally, and especially when we are in campaign mode, we tend to think about what artists can contribute to the action space. We think about how artists can strengthen the will and push people to act. But we should also ask ourselves, “What are the valuable contributions artists can make in the idea space?” Artists don’t think like policy folks. They don’t think like organizers. And this is a good thing. They think big, visionary ideas. We can’t necessarily claim that reading a novel or watching a sci-fi movie—say, Alex Rivera’s Sleep Dealer (2008), a dystopian film about migrant labor—will move people to action, but the experience expands our imaginations and creates a climate where we can be visionary.

For the last 20 years, because funding for both the arts and social services has been cut, artists who wish to contribute to social change have often been tasked with holding community workshops. While this is important, it also means we move further away from giving artists the space, time and resources to create a body of work. Artists are immediately channeled into an action space because their contributions are viewed in transactional ways. We want artists to be able to work across the spectrum of “action” and “ideas,” because they have the ability to inspire masses of people through their fan bases.

As artists, we need to communicate more than what we stand against or why particular policies affect us negatively, because limiting our commentary to such reactions would confine the social imaginary to existing political frameworks and systems that we do not control. We should also present our vision for who we are, and show why that vision is a positive one. Working in the realm of ideas does not take energy away from the action space. Cultural strategies are as necessary as political strategies.

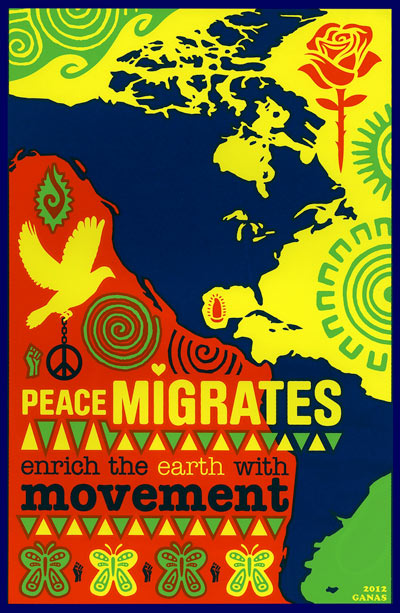

When people claim that “cultural strategy” is just the communication strategy for a political campaign, I disagree wholeheartedly. With communication strategy you are still in the action space, meeting the needs of the campaign or reacting to dominant messages in the media. The idea space presents more complex messages. It allows us to deal with contradictions and gray areas. Take the new concept I have been working on, the idea that “migration is beautiful.” It’s very different to say “No on SB 1070” than to say “migration is beautiful,” because the latter message opens up a positive way of seeing migrants, whereas the former statement simply reacts to an immoral law. So when we talk about tomorrow’s cultural policies, we should think about the whole spectrum of activity, from immediate actions to campaigns to ideas, because we need to give artists the space to develop their bodies of work over years.

Think about culture as rain readying the crops.

To give you a sense of the time frame in which cultural shifts happen, and how that eventually translates into policy, look at LGBTQ culture, which finally made its way onto mainstream TV in the 1990s. Ellen DeGeneres came out in 1997, and Will & Grace started broadcasting the following year. Soon after came the Laramie Project, a play about the life of gay college student Matthew Shepard—who was tortured and murdered in 1998—that was performed in high schools across the country. Just this past week, TIME magazine published its April edition with a title claiming “Gay Marriage Already Won.” The cover story chronicles how the American public moved from considering marriage equality unthinkable to inevitable in less than 20 years. The injection of gay-friendly content into all aspects of our culture, from TV to high-school curricula and even sports, clearly spoke to our collective imagination. It took decades, but we’ve had major policy wins in the LGBTQ sector: hate crimes legislation in the form of the Matthew Shepard Act, the repeal of “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell” and the legalization of gay marriage (in a minority of states, for now, with more progress on the horizon).

Imagine what it would be like if we could have a Laramie Project for immigrant rights, a play about undocumented youth, become popular in high schools. How long would it take us to get to a place where migration was viewed as normal and natural, and where we respected the human rights of people who have crossed national borders?

Timing is important. When is the right moment to inject culture into a political movement? Think about culture as rain readying the crops. You go to the theater, watch sports or listen to music, and culture just happens to you. You’re not expecting to debate the merits of a political message when you listen to music or read a book. You’re more open to how culture is going to transform you, so you walk into it with an open heart. Culture creates a ripe environment for issue-based organizing or “get out the vote” efforts. This is why it’s so important for us to work in unity. We need to understand timing politically to know when it makes sense for cultural interventions to happen.

How can we conceive of artists’ roles in a more expansive way?

It’s especially critical for us to work together in the wake of the dismantling of support for the arts since the 1980s. Upon taking office, Ronald Reagan aimed to eliminate funding for the National Endowment for the Arts (NEA) entirely. He didn’t get there, but when Republicans gained control of both chambers of Congress in the mid-1990s, right-wing groups like the American Family Association pushed them to decimate NEA funding. From a budget hovering between $160 million and $180 million from 1984–1995 (a period during which funding already lagged behind the rate of inflation), Congress brought NEA funding below $100 million in 1996. Since then, we haven’t recuperated. The arts in this country have been devastated.

More specifically, we don’t have a robust infrastructure for art committed to social justice, and social-justice organizations are not hiring artists the way they’re hiring organizers. Artists who are interested in social justice are left without a pathway, even at art schools or music schools. We have to think about how to change this for the long term.

The field of cultural strategy is young. Collaborations between artists and political organizers have definitely happened throughout history, as we saw so clearly with liberation movements like “Black is Beautiful” or the Chicano arts movement in the 1960s and 1970s, and with the anti-apartheid struggles that peaked in the 1980s with widespread cultural boycotts of South Africa. But we have inherited very few cultural institutions dedicated to social justice. Venues like the Los Angeles-based Self Help Graphics & Art, a Latino art center that has united and strengthened a community in need since 1973, are exceptions.

There have been tensions between social-justice spaces and art spaces, too, and that’s understandable; but I think it is important for us to be comfortable with such tensions and take them on in a revolutionary way. This is how we will build the infrastructure and networks needed to help socially engaged artists thrive. Not just 10 or 20 artists, but hundreds, and while they’re young and excited to shape the world around them.

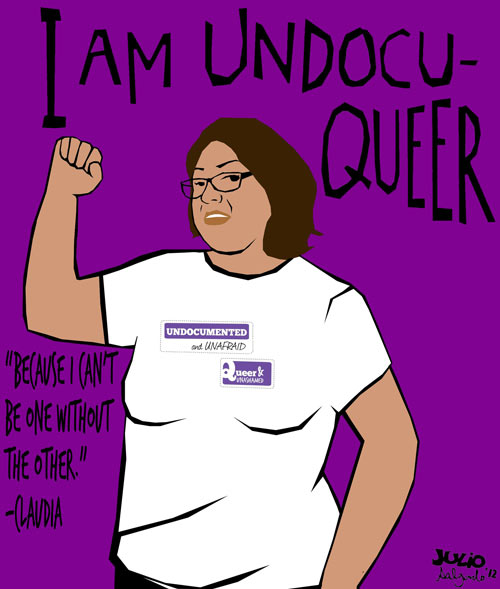

A real cultural strategy is going to require solidarity. A vibrant cultural space is going to require risk-taking. Many of us haven’t figured out how to measure the impact we’re having on the world of ideas because we stay in the action space. We’re not thinking about the kind of transformation that will happen five years from now in someone who, for example, looks at the art of Ramiro Gomez Jr. or Julio Salgado, or listens to a song by Ozomatli. How will their values shift?

Raoul Deal, Stop Breaking Up Families, 2012

To develop long-term rubrics, we should think about cultural shifts in three areas. First, narrative-shifting. What can we do immediately to make pro-migrant culture cool through music and art? We need to push anti-migrant policies to the extreme fringes, as LGBTQ rights activists did with anti-gay messages. Gay-straight alliances are now the norm in high schools, which wasn’t the case 20 years ago.

Second, infrastructure-building. The gutting of the public sector created a huge commercial sector that dominates art schools and art institutions. So while we think about creative strategies for mobilization, we also have to rebuild the space for artists to engage in public service. How are we developing artist leadership in the field of cultural organizing, which is about merging our social justice practices with our art practices? How can we bring more resources to artists, especially undocumented artists?

This leads us to the third area: creating cultural policy oriented toward access and equity for artists. In many ways, artists are seasonal workers; their practice does not bring them a steady workflow. There is very limited funding for artists who have papers. If you don’t have papers, the likelihood of your getting public arts funding is pretty much nonexistent. Furthermore, schools focused on art or music haven’t caught up with math and science schools in accepting undocumented youth. What policy changes do we need to make in the national arts infrastructure so that our field can grow, and so that we are respected by both the art world and the social-justice world?

We have come a long way in the last few years. We should be proud of the work we’ve done and think about taking it to the next level. How can we conceive of artists’ roles in a more expansive way—not just making posters, but also contributing visionary ideas for social change? There are many important short-term needs right now, but we need to look beyond immediate concerns and build up all the forces in our movement, until it becomes an unstoppable wave.

This piece is a collaboration with Culture Strike and can be found on their website.