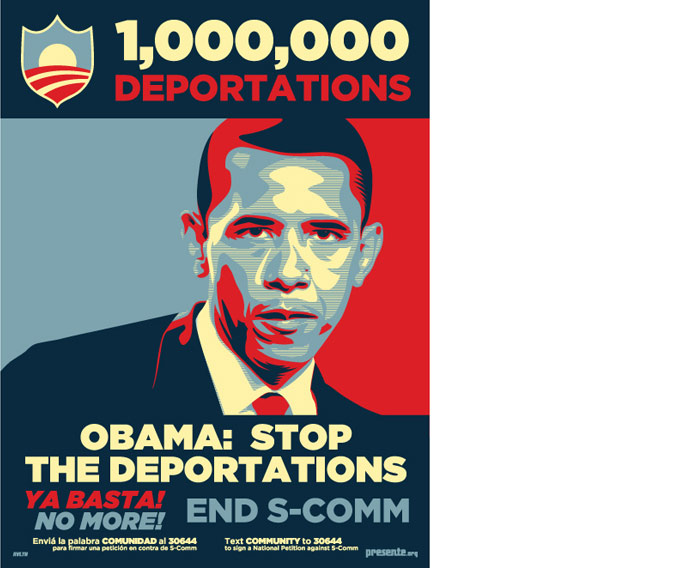

Poster by Cesar Maxit, 2011.

A Creative Time Reports and Culture Strike collaboration

On a recent Friday in the nation’s capital, visitors to the U.S. Capitol, the White House, and other white-walled centers of global power dotting the National Mall stood beneath sunny autumn skies papered with colorful dreams. Literally. Thanks to a collaboration between artists and DREAM Act activists (aka “DREAMers”), images of faces representing millions of undocumented youth gleamed on kites in the upper echelons of Washington. Their stories have come to the forefront of a national immigration debate that, until recently, excluded them.

Writing in the same unequivocal tone that forced President Obama to grant DREAMers a temporary, but historic, stay of deportation, the organizers of the Dream Kites project declared its simple objective: “to highlight a flawed system and request that we turn our attention onto the current state of inadequate immigration reform.” With the help of artist Miguel Luciano and Culture Strike, an organization bringing artists and activists together in the U.S. immigration debate, images of Dream Kites glided onto the front page of the Washington Post, along with the stories behind them.

Artist-enabled people power has found new ways to soar above the money-enabled Powers from Above.

The kite action reflects how the wings of artistic and political imagination are helping the immigrant rights movement grow beyond the multimillion-dollar policy designs of national immigrant rights groups. The latter have remained largely uncritical of President Obama, even as he has deported 1.4 million immigrants (including many DREAMers), a record for a single term in office. On the eve of another national debate about immigration reform, artist-enabled people power has found new ways to soar above the money-enabled Powers from Above.

My current understanding of the role of culture and cultural workers in immigrant rights and other social movements has its roots in Latin America, the source of most human and butterfly migration to the U.S. It was in El Salvador—the tropical, forested land of my parents—that, after graduating college, I first came to know the Tree of the (Cultural) Knowledge of Good and Evil. Slowly, my time in El Salvador withered away my former college radical’s cold aversion to protest songs, to poetry, to the delicate stencils of the talleres culturales (“cultural workshops”) there as no more than the work of revolucionarios de escritorio (“desktop revolutionaries”). I developed an altogether different sense of the political and the cultural—and the transformative, silken space between them. I learned how words could be liberating, but also dangerous. After government, media or right-wing civil society groups eviscerated the humanity of nuns, priests, peasants or students by labeling them comunistas or subversivos, they sometimes ended up being persecuted or killed.

In the face of such abuse, artists have often been the earliest adopters of the call to see immigrants for what they are: human.

Cultural struggles to preserve, protect and promote the humanity of all—like those of the butterfly-bearing activists—have been and remain paramount to disrupting the violence of state and non-state actors: psychological violence, physical violence and the violence of bad policy. In the face of such abuse, artists have often been the earliest adopters of the call by rights activists to see immigrants for what they are: human. It was novelist and Nobel Laureate Elie Wiesel, a conservative, who gave the Central American refugee movement what became the international slogan of immigrant rights: “No Human Being Is Illegal.” Since he spoke these words, more left-leaning artists have reproduced “No Human Being Is Illegal” and other pro-migrant memes and messages in rap lyrics, digital images, t-shirts, posters, poems, films, chalk drawings and many other media.

Some 25 years and several local, national and global campaigns after I made the “hard” distinction between the “concrete” work of “real” political organizing and what I saw as the more ancillary work of artists, creative interventions like the kite action have turned me into a cultural believer. Of special note is the symbol of the butterfly, a new face for the immigrant rights movement. As a bearer of beauty symbolizing the life force (the Greek word for butterfly is “Psyche,” also meaning “soul”), the butterfly appeals to everyone’s humanity at a time when the dehumanization of immigrants fuels multimillion-dollar industries in lobbying, media, electoral politics, prison construction, border and other security industries.

I recently witnessed the symbolic flight of the political butterfly during a misty exam week at UC Berkeley. Students rushing in and out of the Life Sciences building were momentarily startled out of their concentration by an image of a blue and white butterfly with the word “MIGRANT,” and the phrases “All Humans Have a Right to Migrate” and “All Migrants Have Human Rights,” drawn in chalk. “Don’t step on it! It’s art,” said one student to her classmates. Another student, a 20-year-old political science major named Andrea Lahey, said: “You can’t really argue with the message because being human is not controversial—we’re all human.” Hours later, the DREAMer butterfly was washed away by evening rain. But, like the colored dust left by the pollen-covered wings of a butterfly, the DREAMers’ image had already made its mark, turning the prosaic activity of walking to and from science class into a poetico-political act.

The DREAMers’ butterfly at UC Berkeley, 2012. Photo by Roberto Lovato.

None of the “leaders” of the Washington-based immigrant rights groups with national media clout is an immigrant. That’s right: none.

Forcing the country to face social issues through cultural interventions is especially critical for a grassroots U.S. immigrant rights movement, given that none of the “leaders” of the Washington-based immigrant rights groups with national media clout is an immigrant. That’s right: none. This is one reason why it is so important to stage protests with powerful images of immigrants and symbols of migration: for example, displaying digitized DREAMer posters that depict butterflies yelling “Our Voices Will Not Go Unheard” into a megaphone, or more directly, getting undocumented writer José Antonio Vargas, undocumented artist Julio Salgado and other DREAMers on the cover of Time magazine under the heading “We Are Americans.”

Artists will need precisely this kind of political imagination to confront the extraordinary and unprecedented challenges facing immigrants. By working together, artists and activists have exposed Barack Obama as the worst U.S. president ever in terms of persecuting, jailing and deporting—and, I would argue, terrorizing—mostly innocent immigrants, including children. Washington-based artist César Maxit’s powerful image of a sinister-looking Obama accompanying the message “1,000,000 Deportations. Ya Basta! No More! Obama: Stop the Deportations” took big risks that paid off. The image became iconic, appearing in national newscasts, mass protests, online videos and other media as it went viral, despite disapproval from Obama’s powerful allies within the immigrant rights movement. In the process of putting potent and uncompromising images before the public, DREAMer and other immigrant activists and artists have redefined the relationship between Latinos and both major parties.

As we enter a super storm of intersecting and rapidly growing global crises—economic decline, food shortages, climate change, etc.—that are leading migrants to embark on their often-breathtaking journeys, the truth-telling work of artists and cultural activists has taken a definitive turn. Foregrounding immigrant beauty, immigrant freedom and immigrant solidarity in order to disarticulate the myths manufactured by the anti-immigrant industries, as the Dream Kites and butterflies do, is still vitally important. But, because of the astonishing confluence and complexity of these crises, engaged artists must not only fight dehumanization but also craft a constructive path towards the social equilibrium necessary to decimate anti-immigrant hatred everywhere. Through the storm, the perilous flight to freedom continues.

This feature is a collaboration with Culture Strike and can be found on their website.