On March 13, 2004, I went to the Madrid headquarters of the conservative Partido Popular, the political party in power at the time, to protest the war in Iraq and its consequences—including the terrorist attack that killed 191 people in Madrid only two days prior. Nobody had organized the demonstration. I got word of it by text message and e-mail, and I still don’t know who sent the messages to me.

Never before had I been summoned like this. Previously, when I attended an event, whether a protest or a party, it was because someone had bothered to prepare it. But for March 13, no one had prepared anything. The thousands of us who took to the streets did so without knowing where we were headed. We responded to an announcement that came out of nowhere or, more precisely, out of a general discontent.

The March 13 action was born with no name, no brand and no organization. Everything surrounding that event signaled something tremendously new for me. I had imagined something like this before, as I considered how emerging communications technologies would lead to unexpected social behavior. But it wasn’t until that day that I experienced this first-hand.

No one knew what to call it. An intelligent multitude? A connected anonymity? We were witnessing an unknown force, one that appeared by surprise, turned everything upside down and disappeared as quickly as it had arrived. I now call it the Nameless Force.

On the day before general elections in Spain, labeled a “day of reflection,” all political campaigning is illegal. Yet here we were, just hours before it would be time to vote. If someone had told me about the protests earlier, I wouldn’t have believed him. Thousands of people disobeying the law and protesting against the government on a day of reflection? Lies! Impossible! And yet, that’s what happened. The experience transformed my understanding of politics.

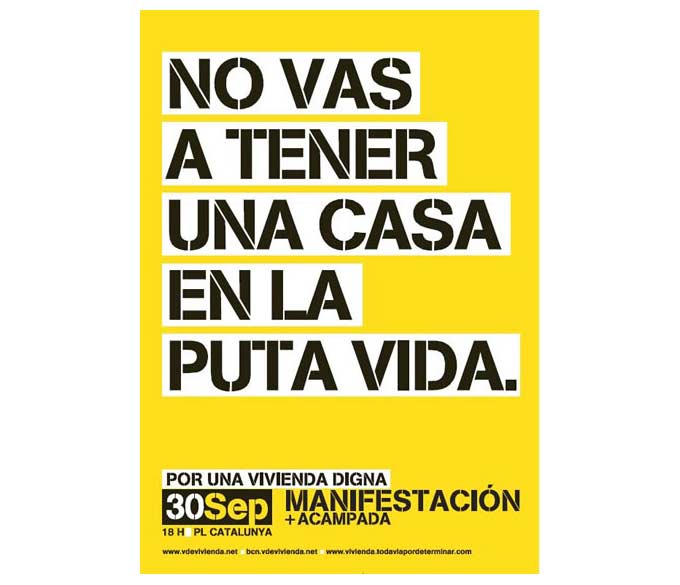

Poster for the V de Vivienda movement, 2007.

Some time passed before I felt it again. But then it happened—another email from an undisclosed sender hopped from inbox to inbox, into mine. The announcement came from V de Vivienda (“H for Housing”), a movement that emerged in 2006, and called for the right to decent housing and an end to real estate speculation. Once again, an anonymous voice expressed a general discontent. Once again, the Nameless Force—perhaps a bit less unknown this time around—was ready to change our lives.

The difference between this moment and 13M was that, this time, the Nameless Force didn’t disappear. It settled into our lives for a spell. Still, nobody could represent it—except through that declaration which quickly became its battle cry: “You’ll never own a house in your whole fucking life.” Like everything the Nameless Force has spawned, the phrase decisively broke from political common sense. It offered no hope—no “Yes we can!”—and no future (not even “a future with no poverty”), but it nevertheless lit the collective imagination as gasoline feeds a fire.

This second experience with the Nameless Force made me realize that there was no turning back, that the politics we had known until then was obsolete, that nothing we had done before was useful anymore and that, from this moment on, all social protests were going to be anonymous, direct and impossible to represent. Like the “world record” we set for the most people shouting, “You’ll never own a house in your whole fucking life” (sadly, Guinness wouldn’t recognize our feat). An event that gathered thousands and thousands of people in cities all over Spain to shout, collectively and publicly, what had been experienced until that moment as a personal problem.

People at a street protest in Madrid shouting “You’ll never own a house in your whole fucking life,” 2012.

In the last two years, we’ve witnessed the Nameless Force on many occasions and in many different places: Egypt, Tunisia, Libya, Spain and the U.S., among others. We’ve called it Occupy Wall Street, #Spanishrevolution and countless other things because the Nameless Force truly has no name and no use for one. As has become customary, the Nameless Force has done as it pleases. It has occupied plazas and streets and broken the law. It has avoided the pitfalls of political representation and shown that nobody can represent it. It represents itself with the broadest slogan: “We Are The 99%.”

This May, when the Spanish government decided to inject an additional 19 billion euros of public money into Bankia—the nation’s biggest mortgage lender, which had already received a bailout of 4.5 billion euros—so that it wouldn’t collapse like Lehman Brothers, the Nameless Force called on us once again: “Take your savings out of that damn bank!” Adding: “It’s better for it to go down than for all of us to.”

A bunch of anonymous actions took place immediately afterwards. One of them was the “Close Bankia” party, which I participated in. A group of indignados (as #Spanishrevolution activists are now known) met in the morning, and we went to a Bankia office (it didn’t matter which). There we waited, undercover, until we saw a woman close her account. You can see our reaction in the video below. What a party! Finally, something fun amidst all the cuts, layoffs and scams.

The Spanish artist collective Enmedio throws a “Close Bankia” party in Madrid, 2012.

In a matter of hours, the above video received more than half a million hits. But that’s not enough to vanquish Evil, and the Nameless Force knows it. That’s why a couple of months later, it called on us again for the largest and riskiest venture yet: Surround the Congreso de los Diputados (Spain’s Congress) until the government stepped down.

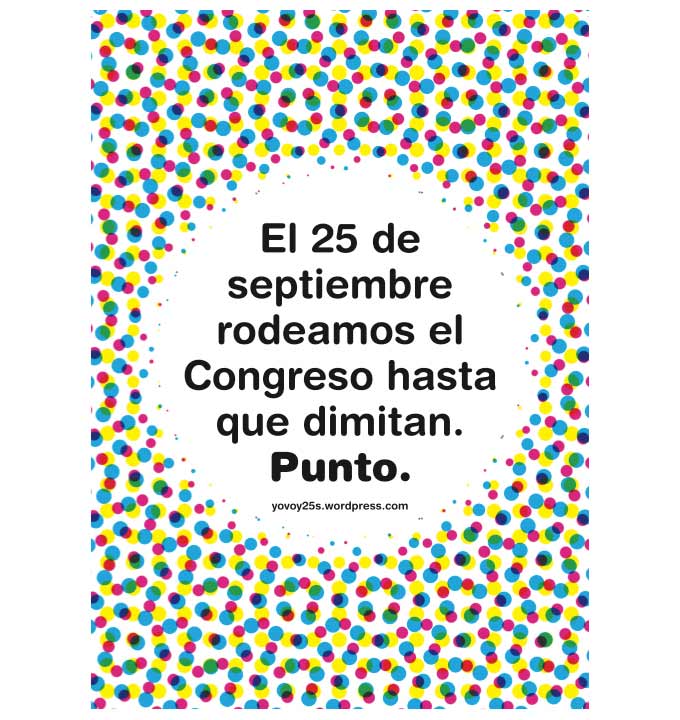

Enmedio’s poster for the 25S protests at the Congreso de los Diputados in Madrid, 2012.

Provoking the downfall of the government to initiate a new, citizen-run constitutional process seemed like an excellent idea to my friends and me. We got to work immediately. First we designed a poster full of colorful dots around the phrase “On September 25 we will surround the Congreso until they resign. Punto [Spanish for ‘dot,’ ‘period’ and ‘That’s it!’].” We printed thousands of them and put them up everywhere. Then, once everyone had heard the call, we hit the streets with our cameras and took part in “Photocall 25S.” We collected photographs of people holding colored dots on which were printed their reasons for surrounding the Congreso. Those photographs spread across the internet, capturing the attention of the press for weeks.

Enmiedo, Photocall 25S, 2012. People photographed in the streets of Madrid holding colored dots, which were printed with their reasons for surrounding the Congresco on September 25. Photo by Oriana Eliçabe.

A few days before the 25S action, the government announced that over 2,000 police would barricade the Congreso during our planned protest. The move made it impossible for us to achieve our goal, at least by land. So we organized the Discongreso. We decided to turn those colorful dots into discos (Spanish for “Frisbees”) and see if we could try by air.

Through social networking, we asked people to get Frisbees and write their own ideas for our democracy, or rather for a political system worthy of the name “democracy.” When September 25 came around and I saw hundreds of people with their marked-up Frisbees ready to be tossed at the Congress, I couldn’t believe it. Boys and girls, people young and old: all types were there, slinging Frisbees with slogans like “People first,” “Ban the debt,” and “No bankers will ever govern a country again.”

Throwing Frisbees, hearing people shout and watching them launch Frisbees towards the Congress, I realized that my own problems were shared by many others. Seeing those discs fly over the police was a perfect metaphor for the current situation in Spain, where democracy is truly in the air.

Enmiedo, Discongreso, 2012. People holding marked-up Frisbees ready to be tossed at the Congress. Photo by Oriana Eliçabe.