For well over a year, we were inundated with an electoral campaign between two parties committed to continuity. Even when they spoke of change (and the party out of power always speaks of change), they meant more of the same. Change, real change, is what they fear above all else. Every four years, we go through a ritual of change that does little more than guarantee that the system will remain intact, benefiting the have-mores, placating the haves, and screwing the have-nots.

It’s no wonder, then, that people turn to movements. Any change we can believe in comes from us moving together. Occupy Wall Street opened up the possibility of such change. Unlike any movement in contemporary U.S. history, it challenged the capitalist system, confronting banks, corporations, and the pervasive, unjust effects of predatory neoliberalism. As it ruptured the hold of Wall Street on our collective imagination, it incited a new willingness to work together in building our common future.

Where are we now, exactly one year after Occupy Wall Street was evicted from Zuccotti Park? Until recently, sympathetic as well as critical commentators were proceeding as if Occupy had gone the way of a mainstream campaign, raising hopes but changing nothing. Then, with Occupy Sandy and Strike Debt, came an upsurge in support for Occupy. These new initiatives demonstrate the continued power of Occupy to tie together issues and struggles previously pursued as if they were politically separate or even competing with one another for pride of radical place. The common name of Occupy brings together debt, housing, education, finance and climate as key sites of conflict between the 99 percent and the one percent.

If Occupy is not to go the disappointing way of our mainstream politics, it has to persist as the name we use for our common struggle.

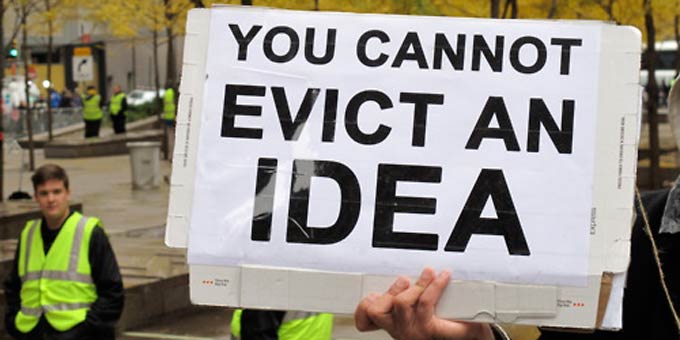

More than any other aspect of the movement, Occupy’s name lives on. People all over the world speak, write and organize in the name of Occupy Wall Street. Exhibitions, symposia and groups assemble under the guiding idea of occupation. Throughout last year, in Zuccotti Park and Oakland’s Frank H. Ogawa Plaza, in Frankfurt and in London, we remade ourselves into a collectivity struggling together under the common name of Occupy. More than the fact of sleeping in parks, more than the practices necessary for maintaining encampments, occupation designated a refusal to stay in the places assigned us by capital and the state. The slogan “Occupy Everything,” for example, expressed the way occupation always signifies more than physical presence. On the face of it, the slogan is absurd—we already occupy everything. What matters, then, is the minimal difference, the shift in perspective that the injunction to occupy effects. It enjoins us to occupy in a different mode, to assert our presence in and for itself—not for the one percent, but in common and for the common.

Some in the movement, particularly in New York, argued that the heart of Occupy is its process: the General Assembly, consensus-oriented discussion, and the autonomy of each individual who speaks only for herself and never for another. For some New York occupiers, then, the movement meant the everyday activity of talking through issues and coming to an agreement about what to do. In September 2011, this made a certain intuitive sense. In the context of a corrupt, exclusive political system, people needed to find ways to rebuild their trust in one another and in themselves. Processes that facilitated participation and collective decision-making were attractive insofar as they helped people build new capacities and connections.

But process became a bible, rules to be followed. Occupy came to be defined in terms of activities, not action. Rather than challenging Wall Street, occupation was attending the 7pm General Assembly in downtown Manhattan. As a result, a structure defended on the grounds of its inclusivity started to function as a mechanism of exclusion—of those who don’t speak English well, of those who work three jobs and can’t attend, of those who care for others dependent on them, of those who live far away, of those who are shy or uncomfortable with a culture or discourse dominating the GA. Rather than cultivating a sense of ourselves as a collectivity, we started using terms like “day 1er,” thereby creating a hierarchy of dedication that relegated new people to the bottom of the food chain. Likewise, we allowed the idea of prefiguration—enacting the emancipated, just community we aimed to build—to reduce an international political movement to the complex of activities involved in holding a park, as if there were no larger struggle against foreclosures, privatization, banking, unemployment and debt. Insistence that the GA defined Occupy drove people away at exactly the moment when we needed them, expected them, to come.

Occupy turned into the very kind of politics it emerged to confront, combat and replace.

Our efforts to construct direct democracy and consensus-oriented discussion resulted in other, similar failures. First, consensus holds groups hostage to outliers. In a group as politically diverse as Occupy, such hostage-taking had conservative effects, generating stasis and hindering results. Second, as we now know, not every decision needs to be made by everyone. When transparency opens up a meeting to police infiltrators, it undermines the very purpose of a meeting. It makes no sense to plan an action in an “open” meeting that might include people whose sole purpose is to disrupt or entrap. Some plans are best made by small groups working in secret, below the radar. It took us too long to acknowledge this because we were handcuffed by a process designed to value participation and consensus above all else. Third, groups operating outside the GA frame lacked respect. Process-fetishism—the displacement of radicalism onto matters of deliberative procedure—prevented us from acknowledging and appreciating what was actually happening: Groups in different neighborhoods, different cities and different countries were springing up and doing actions on their own. This should have been seen as a plus, an indication of the movement’s energy and vitality. Unfortunately, the lack of clarity regarding the relationship between the GA and actions created an irresolvable disconnect between theory and practice.

The process we designed to build trust instead enhanced paranoia and suspicion. We were paranoid regarding any plans about which we remained in the dark. We were suspicious of new people: Were they infiltrators, informants, spies? And we were paralyzed by the fear of co-optation. Ideological purists warned us against working with unions, MoveOn, and other more established groups. Only those participating directly in the movement—those who adhered completely to a stifling process—were counted as members, supporters or allies. No wonder Occupy had a hard time growing!

The emphasis on individual autonomy continues along the same road to dysfunction. Each person is supposed to speak for herself. No one is to speak for another. What is the difference between this emphasis on individual rights to free expression and libertarianism? There is no difference. Individuals can already express their opinions. What we can’t do is express them in ways that matter—this requires collective strength and collective expression, speaking as “We” rather than “I.” Unfortunately, constant emphasis on individual autonomy too often overpowered newly emerging (and thus fragile) common ties. At exactly the time when we needed to do everything we could to nourish and strengthen our commonality, the process that presented itself as Occupy weakened them.

Given the toxic effects of process-fetishism, it’s not surprising that some comrades have had Occupy fatigue. For them, the very term Occupy came to denote endless, pointless meetings, unshakeable suspicion and an alienating, even macho, assertion of individual rights. Occupy both seemed and was bureaucratic and exclusionary. It turned into the very kind of politics it emerged to confront, combat and replace.

The movement became more than its processes the moment people outside New York began organizing themselves in its name.

But Occupy has always been more than the process. It is the common name of movement against Wall Street and for the 99 percent. Attached to images of people engaging in mutual aid, assembling to discuss common concerns, marching in opposition to a common enemy, and working to produce a common future, Occupy has always been greater than the sum of its parts.

If Occupy is not to go the disappointing way of our mainstream politics, it has to persist as the name we use for our common struggle. It must continue to designate a space where, even as we disagree, we come together in opposition to Wall Street. Processes don’t define or constitute Occupy. The movement became more than its processes the moment people outside New York began organizing themselves in its name. At that point, Occupy took on a life of its own, extending far beyond the control or intentions of those who set it in motion.

Many of us long dreamed of creating a political form (a common) that could be adopted and adapted, that would circulate and inspire, in a protean, expressive, horizontal fashion. We imagined a politics capable of exceeding the confines of issues and identities. With Occupy, we have that. So we need to put it to use, not put it away, as some have suggested. Discarding the name we share in common and starting all over would be a costly mistake. Why should we reinvent what we already have when we could be extending, amplifying and empowering it? As has been made abundantly clear with Occupy Sandy, Occupy occupies a place in popular consciousness. We won’t easily get such a place again.

The backlash against Occupy within the movement is perhaps the most pernicious inversion effected by process-fetishism. If process-fetishism turned our efforts to build inclusion into practices of exclusion, our efforts to produce trust into patterns of suspicion, and our efforts to establish commonality into pronouncements of individuality, then it also turned our opposition to eviction inside out such that occupiers themselves are the ones trying to “evict an idea whose time has come.”

We have to occupy Occupy. We have to use the name we have in common for our common struggle, which will entail grappling with its meaning and its future. Struggles over the meaning of occupation, over the name we have in common, have energized us since we began. We are alive not because we agree but because we struggle over our common name. Those who ceaselessly repeat their mantra of leaderlessness—“no one can define Occupy”—miss the point. It’s not that Occupy can’t be defined. It’s rather that Occupy is defined in the fight over its meaning. That’s what makes it powerful.

Not everyone fights in and for the name of Occupy. Those of us who do have to claim the name, knowing that in so doing we claim the fight.

Image © thedustyrebel.com.

This piece, commissioned by Creative Time Reports, has also been published by visualMAG.