Ngwatilo Mawiyoo, View of Nandi in Kenya’s Rift Valley, 2012.

Turbo; pronounced like that engine, except with a definitive and rolling “r,” like the Spanish toro, every bit as strong and vigorous, and more.

Turbo is a little town in Kenya’s Rift Valley, a 45-minute drive from Eldoret along the Eldoret-Malaba highway, toward the Kenya-Uganda border. The town sat along the border of two provinces in the old dispensation. On one side of the highway was the former Western province, and on the other, the former Rift Valley province. Turbo is now, after the enactment of Kenya’s new constitution in 2010, on the border of two different counties.

Locals will quickly note how the border crosses into the western side and “takes” the health center and a granary farther down the road—“takes” them into the former Rift Valley province, that is. The implicit suggestion (true or false) is that someone with eyes on the fortunes of Rift Valley was charged with drawing the lines. It’s the beginning of a ten-day dance about insiders and outsiders, the burden of historic battle lines, the past and the future.

Turbo lies near the traditional line between Nandi and Luhya lands, so these two ethnic groups are dominant. Over the years many people from other communities have settled here, led by the highway, consistent rainfall and fertile land—now covered with ripening maize on stalks more than eight feet tall.

Ngwatilo Mawiyoo, Maize in Kenya’s breadbasket region, 2012.

I called Milkah Songok and explained that I was a writer from Nairobi traveling around rural Kenya, that I got her number from a journalist in Eldoret—hers because of what happened to her son.

May I visit with your family for 10 days? No, I can’t afford to pay you to host me as such, but I could definitely help out in the house, the farm, your business…? No problem, she said, and I blinked on my end of the line, afraid that she had misunderstood me somehow, because in her place I would have asked many more questions.

So here I am in her living room on day one, after the six-hour journey from Nairobi, seeing for the first time the deep blue of her oil-painted living room walls, lined with decorated white netting, creating what looks like a pretty pattern of white flowers on baby blue wallpaper. Above me, hanging from the cured wooden beams that support the iron sheet roof of her red brick home are several bright plastic flowers, which reflect the light from the veiled window.

Ngwatilo Mawiyoo, The Songok home in Turbo, 2012.

High up on the wall, among other prints, hangs a framed photograph of former President Moi, the kind you would have found in offices before President Kibaki took over in 2002. I want to be delicate because Moi is from the Tugen community, who are, like Milkah’s Nandi family, part of the larger Kalenjin community. I need to be delicate not so much because my ethnic group settled on the other side of the country when my ancestors migrated into what is now Kenya, but because we are thought to prefer rival political leaders. I must be delicate because I need to break the ice, and I fear my urban Nairobi sensibilities could lead me astray and ruin my stay in Turbo. I can only guess, and steer away from, what might be offensive.

I do not comment on the A4 size laminated calendar from 2008 either, the one displayed on the wooden cabinet that holds my host mother’s good dishes. It features a portrait of Prime Minister Raila Odinga and the former Minister of Agriculture William Ruto, who remains Member of Parliament for the Eldoret North area. Both flank my host mother, who smiles in the middle.

This photograph makes more sense to me since Ruto is the most popular politician in the region, even as he is set to stand trial at the International Criminal Court (ICC) for his alleged role in organizing attacks on ethnic groups seen as Kibaki supporters during the violence of 2007–2008. Raila, as we affectionately refer to the Prime Minister, ran against Kibaki and was at the center of the chaos in the ensuing dispute over the election results. The two became the principals of a coalition government. More recently, Raila has parted ways with Ruto, as the ICC case and the March 2013 presidential race have gotten hotter. He is the favorite to win in this election.

—

I’m in this town, in this house, because of what happened to Milkah’s son. He had just sat for the national exam at the end of primary school when he died. The results had been out a few days that January morning in 2008, and he wanted to go and see what he scored. A high mark means admission into one of the best high schools, which sets you on the right path to secure a place in university and the possibility of a good life.

Our Kevin saw that he had done well. After checking their scores, he and his classmates headed back from school eating sugar cane. They crossed the bridge and walked up the hill on the dirt road toward home, laughing and jiving as only 12- and 13-year-olds safe from the mortal madness of this most recent political crisis might do.

Ngwatilo Mawiyoo, Boys play on the Tapsagoi hilltop, 2012.

The young boys started to climb the hill. Further up there was a policeman at his station, angry and drunk, beside himself. Some say he muttered, Leo nitaua mtu— “Today I will kill someone.” Every Raila and Ruto supporter had been mad for days upon hearing the unexpected news that Kibaki had won the election. This man was no different, except he was a law enforcement officer, and carried a firearm.

Perhaps he heard the boys walking excitedly and feared them to be marauding youth; perhaps he was too drunk to know what he was doing.

He shoots into the air. The boys scatter. Kevin catches the bullet in his thigh, as if it were a curveball shot out of the policeman’s firearm. He bleeds out before he can reach a hospital.

Kevin and his family are Nandi, as is the belligerent policeman, and likely all the boys who accompanied him. Violence stopped being orderly—divided along the expected lines—in Kenya a long time ago.

The policeman is transferred; no action is taken against him whatsoever. Kevin’s family is successfully discouraged from even filing the case. The child is buried at his parents’ home, behind the granary, not far from some banana suckers.

I schedule two separate days to speak to my host father about Kevin. On both occasions he arrives late and drunk. The second time, at two in the afternoon, wearing a somberness drenched in alcohol, he recounts the story of what happened that day, unbidden and in staccato style, pausing often for me to act as chorus during the obvious, senseless parts of the story, in our classic call-and-response tradition.

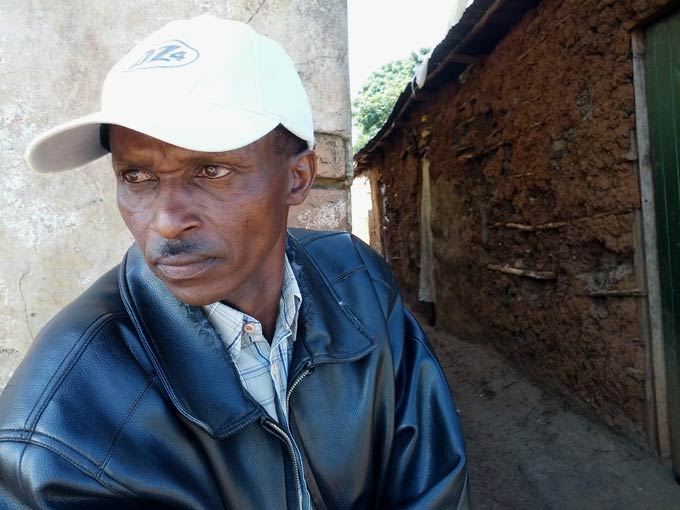

Ngwatilo Mawiyoo, ‘Brazil’ Songok Remembers, 2012.

Ngwatilo Mawiyoo, Milkah Songok Remembers, 2012.

Kevin’s mother is quiet when she speaks about her murdered son; no amount of storytelling for peace or justice will bring him back, or make sleep less godforsaken, less tenuous, less alive to the reality of her absent child.

Chela is the only girl. She has one brother left now, the eldest. Chela is the last-born child of her mother. When Kevin died, she was about 11, spending the Christmas holidays in Nairobi with an aunt. She only heard accounts of how it happened, and didn’t quite understand what it meant. But she made it back for the funeral, despite the roadblocks by angry youth concerned about the fate of a handful of politicians as if it could be their own. She came in time to see them lower the brother to whom she was closest into the ground.

This is the first portion of a two-part report. To read the second, click here.